At least 17 people — including three UN personnel — have died after three days of violent protests against the UN peacekeeping mission in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Demonstrations in the region have now spread to other cities.

On Tuesday afternoon, hundreds of people surrounded and looted the UN base in Goma, demanding its forces withdraw from the eastern DRC. After the Congolese cops were unable to quell the protests, the UN decided to bring its peacekeepers home.

How we got here. The latest iteration of the UN peacekeeping mission in the DRC was established in 2010 to protect civilians in the eastern part of the country. But locals believe the UN peacekeepers have failed to do their job.

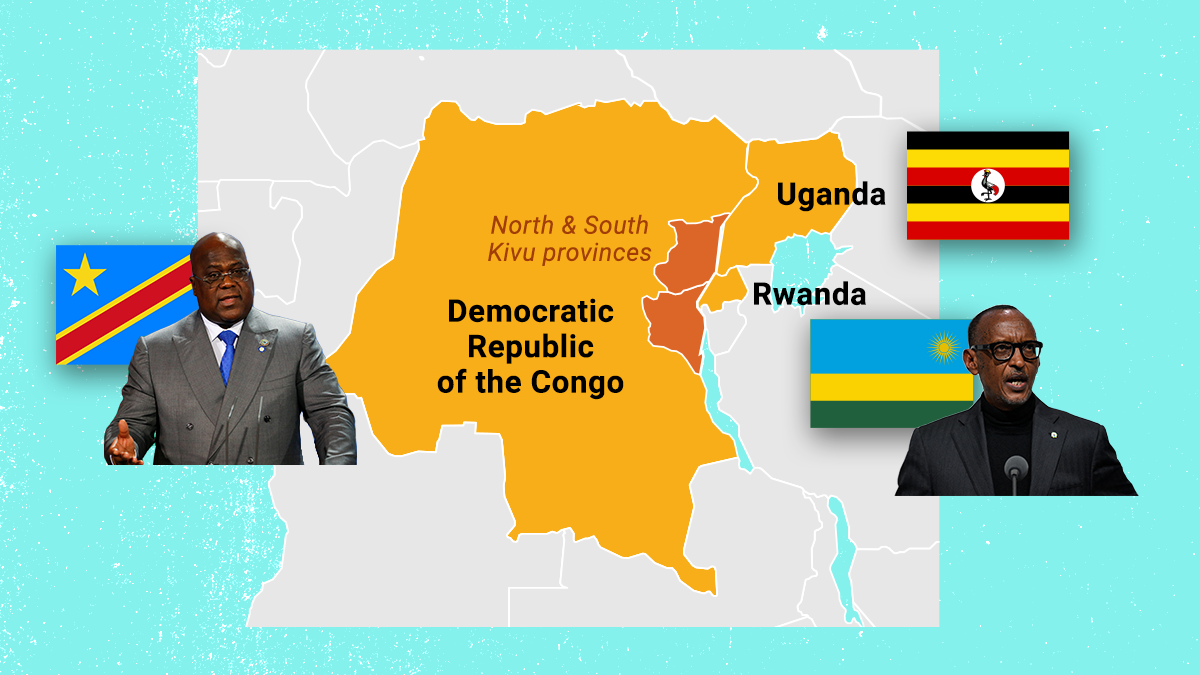

Bordering both Rwanda and Uganda, the eastern DRC is one of the most resource-rich yet conflict-ridden regions in sub-Saharan Africa. It suffered the chaotic exodus from the 1994 Rwandan genocide (committed by the majority ethnic Hutus against the minority Tutsis who now run the country), followed by two wars in 1996 and 1998. An estimated 120+ armed groups are now fighting there.

Things have gotten even worse since November 2021, when the M23 — a DRC-based rebel group claiming to defend DRC Tutsis against the Congolese military — began its latest offensive. Many in the DRC blame the M23's recent gains on Rwanda, which has long been accused of supporting the rebels (which the Rwandans deny).

A month ago, the DRC and Rwanda agreed to de-escalate tensions. But the violence persists, and people are getting tired — which in part explains the rage against the (UN) machine.

Why it matters. “Volatility in that region is kind of the executive status quo,” says Eurasia Group analyst Connor Vasey. But “any sort of intensification of that does create issues.”

And perhaps this time what’s happening is more troubling than the violence the region has seen for so many years.

This popular unrest is precisely what we should be watching out for, says Phil Clark, a professor at the SOAS University of London. The M23’s territorial gains have diverted attention away from what’s happening at the local level.

Never before, he explains, has the eastern DRC seen such popular active opposition, directed against several actors — Rwanda, the DRC government, the UN, and Tutsis — all at once.

“The thing that I think is worrying is how organized [it] is,” says Clark. “You’ve got these local leaders at the provincial and the village level very happily on camera, saying — go out and kill the Tutsis.”

If the protests managed to throw the UN out, it might spur more local unrest that could further worsen an already “combustible situation”.