The small Central American nation of Honduras is in many ways a full blown narco-state. President Juan Orlando Hernandez – who’s governed the country for close to a decade – has been linked to the country’s booming drug trafficking trade. His brother Tony, a former congressman who is buds with Mexican drug lord El-Chapo, was sentenced to life-in prison this year for smuggling cocaine into the US. Narco-trafficking gangs run riot in the country, fueling one of the world’s highest murder rates, while corruption and poverty abound.

In a sign of the hunger for change, Hondurans have overwhelmingly selected an avowed socialist to be the next president, rather than see the conservative Hernandez’s preferred successor take power. It’s a big moment for a country in crisis. What happens now?

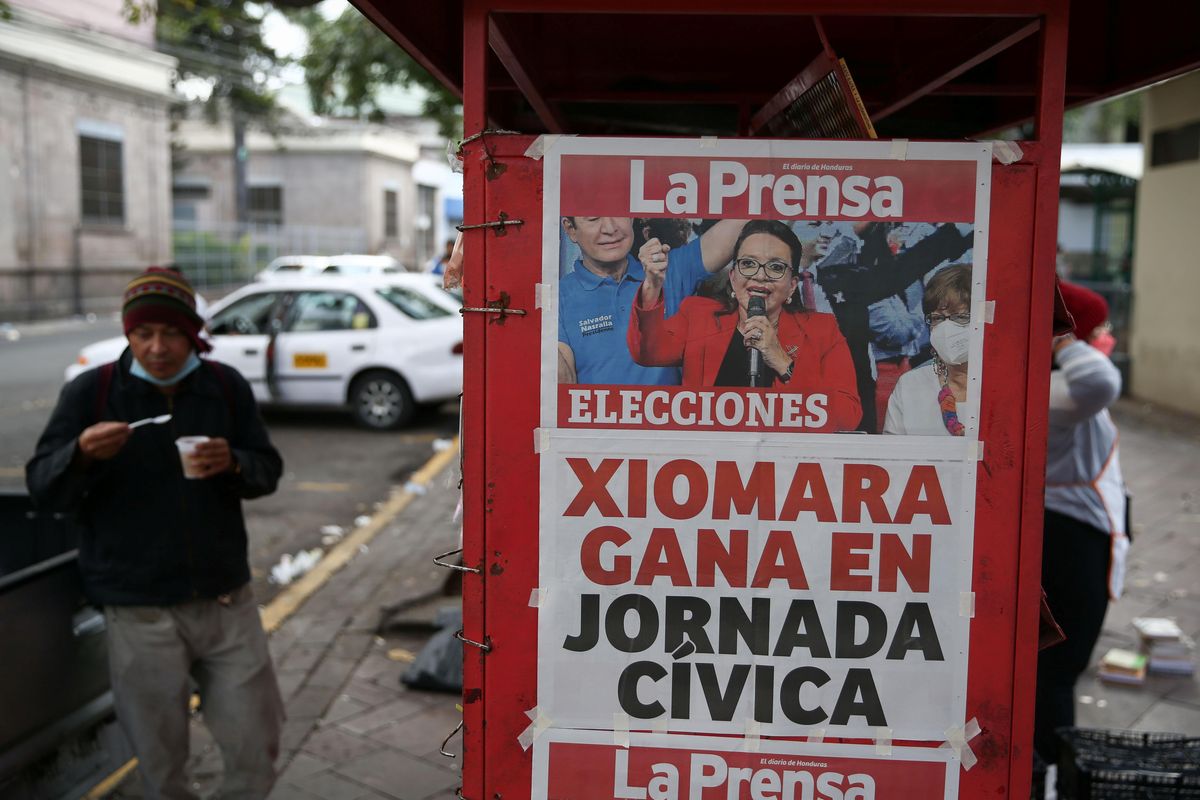

First, who’s won? With most of the votes counted, Xiomara Castro of the leftist Libre party currently holds a whopping 20-point lead over Nasry Asfura of Hernandez’s ruling National Party. That means Castro is now all but certain to become Honduras' first female president. She is in fact no stranger to Honduran politics: her husband José Manuel Zelaya served as president for three years until he was ousted in a military coup in 2009.

Hernandez and his cronies won’t be missed by many Hondurans whose lives are plagued by poverty and gang violence while the political elite gets rich off drug money. In Honduras, one of Central America’s poorest countries, lack of economic opportunity and high murder rates continue to drive high levels of emigration, most notably during the pandemic. The emigration rate from Honduras has increased 530 percent over the past three decades.

Will this development change things? In many ways Castro’s win is a triumph for democracy. The elections appear to have been free and fair, a stark contrast to the post-election violence that resulted after claims of election fraud in 2017.

The 62-year old Castro, who represents a coalition of opposition parties, has said she wants to open dialogue with all sectors of Honduran society to bridge the country’s deep divides. She has positioned herself as a change candidate, vowing to root out graft by establishing a UN-backed anti-corruption commission and to reduce poverty. And although her policy details are scarce, her message has resonated with a deeply disillusioned Honduran electorate that feels it has everything to lose by keeping the ruling Nationals in power.

However, Castro’s wings might be clipped by Congress, if the Nationals and its political allies hold solid ground in the 128-seat chamber.

Who’s watching? The United States, for starters. The Biden administration has made combating corruption a key part of its broader Central America policy, which aims to stabilize the region in order to reduce northward migration. And Honduras is a key piece of this: during the surge in illegal border crossings over the past year, Hondurans were second only to Mexicans among nationalities stopped at the border.

Castro, for her part, says she wants to maintain solid ties with the US, though it is unclear whether Washington and Tegucigalpa, the Honduran capital, will find common ground on a range of issues including relations with China, migration, and security.

Mexico also has a keen interest in seeing a more stable Honduras. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has come under strong pressure – first from Trump, now from Biden – to stop migration flows at his own borders.

Looking ahead. Castro’s job will be to turn stump speech rhetoric into meaningful change that people can feel. Hondurans are desperate for change. The neighbors are watching closely. Can she deliver?