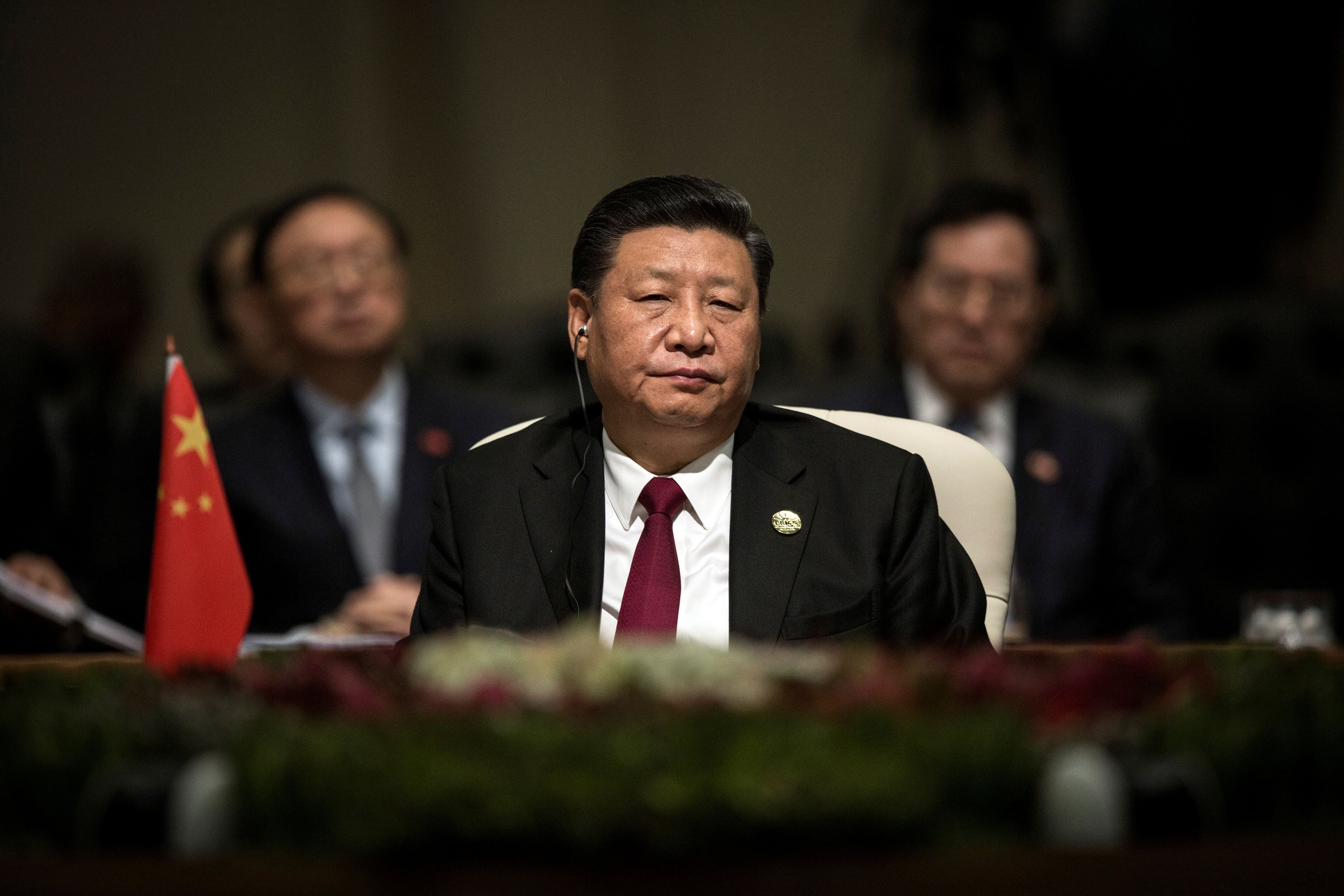

Back in March, Xi Jinping was riding high. Wielding more power than any Chinese leader since Mao, he was feeling good about China’s handle on North Korea and ready to stand toe to toe with Donald Trump on trade. One long, hot summer later, and Xi faces a reality check, with growing pressures on three fronts:

First, there’s the US-China trade fight. On Thursday, the Trump administration plans to slap tariffs on $16 billion worth of Chinese goods, the latest twist in the trade spat between the world’s two biggest economies. Beijing has promised to respond in kind, but the weakness of its tit-for-tat approach is starting to show. China only imported about $130 billion worth of goods from the US last year, so it will struggle to match the US dollar for dollar if Trump follows through on a threat to impose tariffs on an additional $200 billion of its goods. A mid-level Chinese trade delegation due in Washington this week is unlikely to come away with a deal – Trump believes his confrontational strategy is working and is unlikely to back down. It’s clear that this conflict isn’t playing out as Xi had hoped.

The second problem is Xi’s emboldened domestic critics. This summer the Chinese leader faced unusually public grumbling about his leadership style, including concerns about the return of a Mao-like personality cult. Some critics also fear that Xi misstepped by openly stating the country’s ambitions for global leadership, inviting a backlash that could ultimately hurt China.

Finally, there’s growing pushback against China’s aggressive plans for overseas investment, including Xi’s signature Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. During a state visit to Beijing this week, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammed said he would cancel over $20 billion of Chinese infrastructure deals struck by his predecessor amid fears they would saddle his country with too much debt. Belt and Road projects may also face fresh scrutiny in Pakistan, where borrowing to fund a massive Chinese road and rail buildout has contributed to the substantial economic woes facing newly installed Prime Minister Imran Khan.

None of this will threaten Xi’s grip on power, but his no good, very bad summer has exposed a gap between the Chinese leader’s seemingly all-powerful public persona and the messy reality of managing a would-be superpower. In a top-down system like China’s, a leader’s perceived weakness can make it easier for rivals to obstruct his plans or ignore orders that threaten their interests. Heading into the autumn, Xi needs some wins to shore up and justify all the power he’s taken so much time and trouble to amass.