Nestled in the woods of Maryland outside Washington, DC, the Camp David estate -- the president's country retreat -- looms large in international diplomacy as a place where serious business gets done.

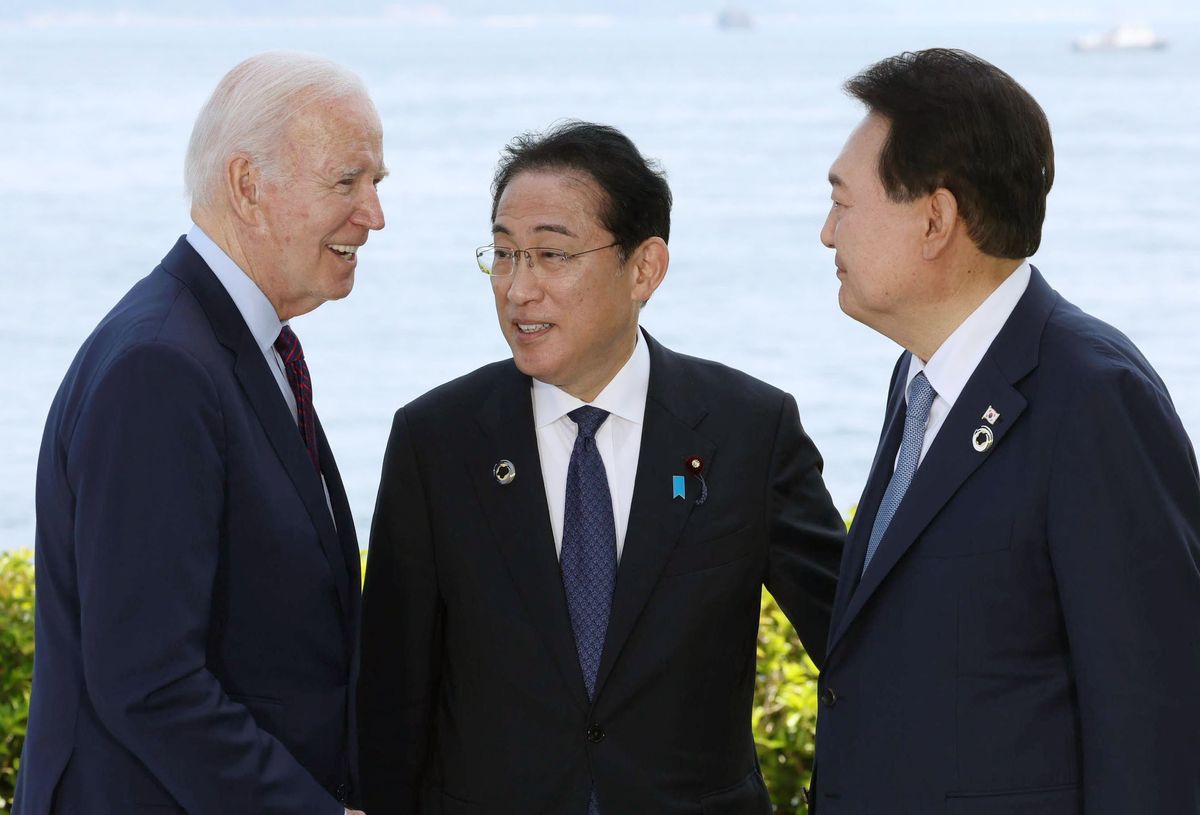

On Friday, President Joe Biden will host South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for a summit at the famous campsite where, in 1978, Jimmy Carter helped broker peace between Egypt and Israel.

While it might not seem like a big deal for Washington to facilitate a summit with America’s two closest Asian partners, it is monumental that South Korea, in particular, appears ready and willing to enlist in a new US-led trilateral alliance with Japan.

Despite a rapprochement, relations between the two East Asian giants have remained strained since Japan ended its 35-year occupation of the Korean peninsula in 1945.

So, what’s on the agenda at Camp David and why is South Korea, long aggrieved by its former colonial power, willing to create this bloc?

The three states will reportedly announce publicly that they will respond collectively to security threats in the Asia Pacific – a big deal considering that Seoul and Tokyo do not have an official security alliance. Trilateral military drills will likely be annualized, while they’ll also announce closer coordination on ballistic-missile defense and cybersecurity.

Clearly, the summit aims to send a powerful message to China and North Korea that these three advanced economies are prepared to combine their military and tech bonafides to protect their collective interests.

Why is this happening now?

Changing of the guard in Seoul. Only two years ago, such a meeting would have seemed nearly unthinkable. Yoon’s predecessor, President Moon Jae-in, broadly seen as left of center, went to painstaking lengths to engage with Pyongyang.

He also oversaw a period of worsening ties with Tokyo over compensation for Japan’s use of Korean forced labor during the occupation. Relations reached a nadir in 2019 when Tokyo placed restrictions on exports bound for South Korea needed to make crucial tech.

But this approach to regional politics took a sharp turn when Yoon, a conservative, came to power in March 2022, vowing to get tougher on China and the North, and to bolster ties with the US. And that’s exactly what he’s done.

But how much of this shift reflects Yoon’s hawkish brand of politics -- or is this a symptom of a broader anti-China shift in Korean society?

“Trilateral cooperation, and the bilateral rapprochement with Japan that have enabled it, would have been unthinkable under former president Moon or Lee Jae-myung, the leader of the center-left opposition whom Yoon narrowly defeated in 2022,” says Jeremy Chan, a China and Northeast Asia consultant at Eurasia Group.

“The big right-left divide in Korean politics is about policy towards North Korea, and the conservatives take a far more hawkish line toward Pyongyang and their backers in Beijing,” he says.

The China angle. China’s increasingly bellicose behavior in the South China Sea has indeed helped the US bring Japan and South Korea together under a joint security umbrella. After all, nothing unites a former colonial power and former colonial subject like mutual fears of a regional superpower.

Crucially, increasingly negative attitudes towards Beijing at home have also given Yoon an opening to deepen security ties with Japan and the US.

Indeed, South Koreans have soured on China since 2016, when Beijing enforced punitive economic measures on Seoul after the US deployed THAAD anti-missile systems on the Korean Peninsula. The US’ aim was to offer a bulwark against Pyongyang’s missile activities, but China said the move constituted a threat to its national security.

Still, it’s a balancing act, as Japan and South Korea’s economies are tightly interwoven with China’s, and neither wants to risk alienating Beijing too much.

What Washington wants. Getting Tokyo and Seoul to act in lockstep has been a key foreign policy priority for the Biden administration as it looks to contain China’s growth. Together, the two Asian states host 80,000 US troops, and South Korea also hosts the largest US overseas military base in the world.

Politically, the bringing together of Japan and Korea can certainly be cast as a win for President Joe Biden, who has aptly capitalized on growing fear in the region to unite two important US allies with a contentious past.

China’s fear: Asian NATO. “China is watching for how far trilateral cooperation moves forward after the summit, particularly in terms of defense and security,” Chan says, adding that, “Beijing’s greatest fear is the emergence of a trilateral military alliance akin to an Asian NATO on its border.”

What’s more, Beijing will be looking to see whether there are any new agreements on tech that might give an indication, Chan says, of just “how far each country is willing to go in moving away from China economically.”

- The Camp David summit - GZERO Media ›

- Ian Explains: How is America's "Pivot to Asia" playing out? - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: Unpacking the complicated US-Japan relationship with Ambassador Rahm Emanuel - GZERO Media ›

- Would US-Japan ties be hurt by a Trump re-election? - GZERO Media ›

- Ian Explains: Xi Jinping's nationalist agenda is rebuilding walls around China - GZERO Media ›

- Why South Korea's president declared martial law - GZERO Media ›