The dumbest recurring character in US politics (no, not the one you’re thinking), the debt ceiling, is back with a vengeance for yet another season of wholly unnecessary drama.

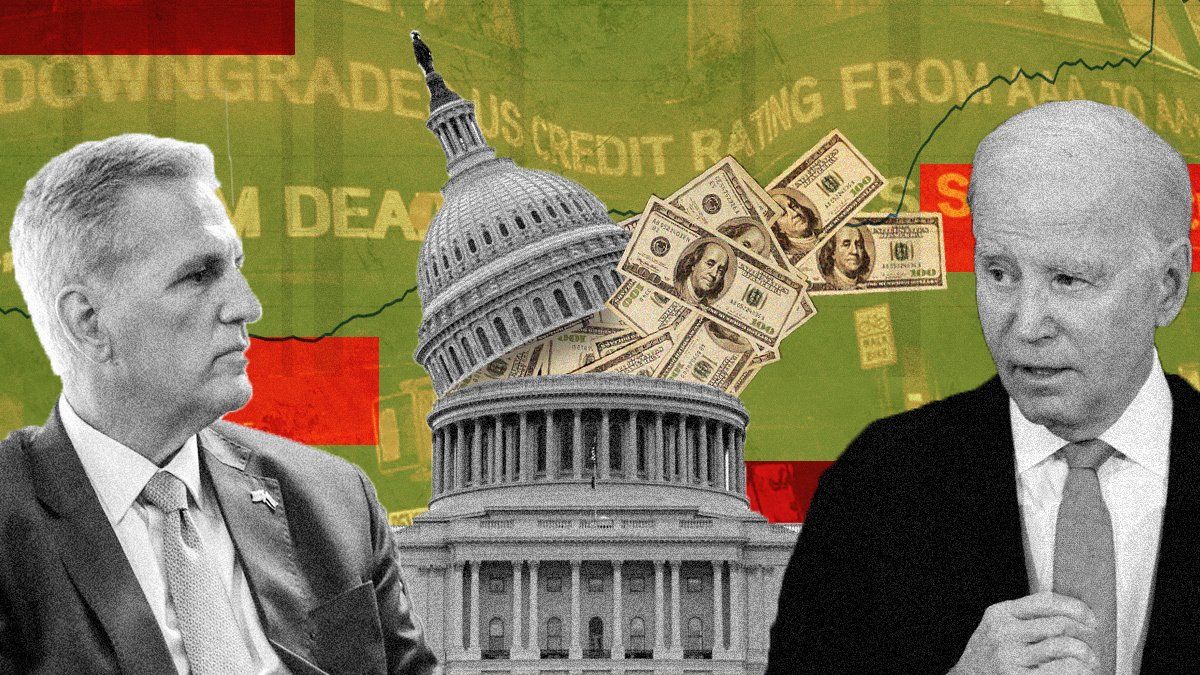

After trading a series of ultimatums, President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy met at the White House on Tuesday to discuss how to defuse the looming crisis. Predictably, the meeting ended without a breakthrough.

This year’s fight will be the most contentious and dangerous since 2013 – the last time we had a disruptive standoff over the debt limit that pushed the US to the brink of default. House Republicans are demanding deep spending cuts in exchange for a debt-ceiling hike, while the president insists he’ll only agree to a “clean” increase without preconditions.

Here's what you need to know about the debt limit, why it matters, and where we’re headed.

What’s the debt limit?

The US Constitution gives Congress the sole power to decide how much money the federal government spends. When Congress authorizes more spending than the government collects in revenue, the Treasury Department has to borrow to finance the deficit. Every time the Treasury issues new debt to pay the government’s bills, it adds to the national debt.

For many years, Congress had to approve every bond that was issued by the Treasury, but as debt issuance became more common, that became too burdensome. In 1939, Congress set a statutory limit on how much the Treasury could borrow without having to come back for approval every time: the debt limit.

Whenever the stock of outstanding debt reaches this arbitrary number – currently set at $31.4 trillion – Treasury isn’t allowed to borrow any more money unless Congress agrees to raise the cap. If the debt ceiling isn’t raised before Treasury runs out of cash, the government is rendered unable to pay its bills.

The debt ceiling has been raised 78 times since 1960, largely without much drama. The exceptions were the showdowns in 2011 and 2013, when Republican lawmakers threatened not to raise the debt limit until the last minute in order to extract policy concessions from President Barack Obama, pushing the nation to the precipice in the process.

What purpose does it serve?

The debt limit makes no sense as a policy tool. All it does is artificially constrain the government’s ability to meet the spending commitments previously mandated by Congress. As former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan put it, the limit is “either redundant or inconsistent” with the spending legislated by Congress in its budgets.

If Congress wants the government to spend less, it can pass laws that mandate that. But debates about fiscal policy should happen before, not after, Congress has approved a budget. By the time it has done that, it has automatically committed the government to foot the bill.

Neither Joe Biden nor Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has the legal authority to spend less than what Congress has mandated. Nor does the US government have the legal option to renege on its obligations.

By not raising the debt limit, Congress stops the implementation of the laws it itself already passed. That’s what’s so absurd about this. Telling the government to spend $X while forbidding it from borrowing enough money to pay $X is like running up your credit card but refusing to pay the tab.

When is the US expected to hit the debt limit?

Technically, the US already hit its debt limit of $31.381 trillion on Jan. 19. Since then, Treasury has been relying on “extraordinary measures” (read: accounting tricks to free up cash) to continue paying America’s bills.

But extraordinary measures can only buy so much time. Beyond a certain date, the so-called “X-date,” the government’s cash balances will be exhausted, and Congress will need to raise or suspend the debt ceiling in order to avoid defaulting on at least some of the government’s bills.

Last week, Yellen sent a letter to Congress warning the US could run out of cash as early as June 1. While that’s probably a conservative estimate, we at Eurasia Group expect that the X-date will come in mid-June. If Treasury can hold out until the June 15 tax filing deadline, it can potentially make it into mid-July, but it’s very unlikely that cash will last through August.

What would happen if we breached the debt ceiling?

If we get to the X-date and Congress doesn’t raise the debt limit, the government will be unable to pay all its obligations in full and on time. That means payments of things like Social Security and Medicare benefits, food stamps, and military wages would be delayed, depriving millions of Americans of income they were promised and were counting on to make ends meet. Depending on how long the standoff lasts, the economic impact of this could be severe.

The worst-case scenario would be if the government is forced to miss a debt payment to a bondholder, triggering a technical default. A default – the first in modern American history – would undermine the full faith and credit of the United States, roil global markets, and likely cause a recession.

In the event of a breach, Treasury would have to “prioritize” payments to delay a default for as long as possible by ensuring that bondholders got paid before the likes of retirees, veterans, and government workers. Some Republicans in the House believe payment prioritization means the threat of default is overstated, but the fact is prioritization would buy a finite amount of time before the government is forced into default. Credit rating agencies might also consider prioritization a partial default and downgrade the US accordingly.

The Council of Economic Advisors estimates that an extended breach of the debt limit could lead to up to 8.3 million job losses, a 6.1-percentage point hit to US GDP, and a 45% decline in the stock market. Even a short default or the mere threat of one would cause damage to financial markets and the US economy.

While the debt ceiling has never been breached before, the 2011 standoff led to a downgrade of the US credit rating that increased US borrowing costs and added to the debt (exactly what you wouldn’t want to do). Actually defaulting on debt payments voluntarily (as opposed to due to an inability to pay) would be the best way to destroy confidence in the US dollar and jeopardize its global reserve currency status.

What’s actually going to happen this time?

That’s up to McCarthy and Biden. With less than a month to go until the earliest estimates of the X-date, they’re nowhere near reaching an agreement. But at some point they’ll have to.

Coming in the run-up to the 2024 elections, the president has an incentive to act responsibly and get a bipartisan deal done that avoids default. While he’d much prefer a clean increase, he knows McCarthy can’t agree to that without losing his gavel. That means Biden will be amenable to long-term spending caps in exchange for a debt-ceiling increase that lasts until after the election.

But McCarthy has to be willing to agree to that, and the speaker has an incentive not to budge for as long as he can avoid it. In fact, to keep his job – his top priority – with such a narrow and divided Republican majority, McCarthy needs to play hardball until the market and constituent backlash to the risk of default gets so bad that it makes it politically safe for him to pass a debt-ceiling increase (whether short-term or long-term) with Democratic votes. Any compromise before then will open him up to challenges from the right wing of his party and almost surely lose him the speakership. The worse the consequences of no deal get, the more political space he’ll have to compromise.

The problem is that investors and most Americans aren’t too concerned about the risk of default because they’ve seen this movie before and the debt limit has always been raised in the end. That means it’s possible they won’t react forcibly enough to shake Republicans out of their complacency until after the X-date, at which point it may be too late to avoid default.

If I had to bet, I’d wager that as the June X-date draws closer and markets show signs of distress, Biden and McCarthy will agree to a last-minute, short-term extension that kicks the can down the road and buys them more time to negotiate. This could happen multiple times until both sides feel enough pressure from market turmoil and constituent backlash that they’re finally incentivized to agree to a longer-term increase in the debt ceiling. Whether they’ll have to go beyond the X-date to get there is anyone’s guess, but the point is that the crisis needs to be big enough before it can force decisive action to solve it (sound familiar?).

One thing is clear: Sooner or later, the debt limit will be raised. The only question is how much damage gets done along the way.

Are there any alternatives?

Well, yes. The debt ceiling is a crisis of Congress’s own making, and Congress can make it go away with the stroke of a pen. There just need to be enough Republican members willing to do that (news flash: there aren’t).

Folks have proposed a number of wonky workarounds, such as minting a trillion-dollar coin, invoking the 14th Amendment, and issuing premium Treasury bonds. None of these untested (and possibly illegal) gimmicks are as good as bipartisan legislation, and under normal circumstances, no one serious would (or should) remotely consider resorting to them.

The only reason why I’m even mentioning them and the White House refuses to rule them out is that if Congress fails to do its job, the alternative – defaulting on US debt – would be even worse.