Happy Friday, everyone!

I’m still in Nantucket so you know what that means… You ask, I answer.

Note: This is the second installment of a five-part summer mailbag series responding to reader questions. You can find the first part here, the third part here, and the fourth part here. Some of the questions that follow have been slightly edited for clarity. If you have questions you want answered, ask them in the comments section below or follow me on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn and look out for future AMAs.

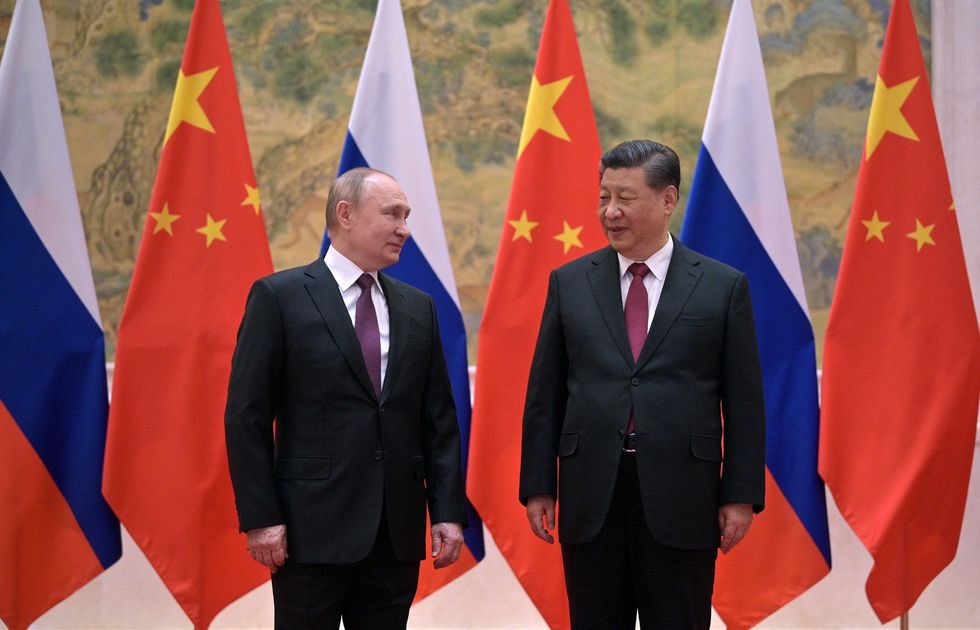

Xi Jinping won't repeat Putin's Ukraine mistakes by invading Taiwan.Alexei Druzhinin/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images

Xi Jinping won't repeat Putin's Ukraine mistakes by invading Taiwan.Alexei Druzhinin/Sputnik/AFP via Getty Images

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Has the Russian experience in Ukraine served as an incentive for or deterrent to Chinese aggression against Taiwan? (Conrad S)

It’s been a deterrent. While it’s no secret Xi has designs on Taiwan and views U.S. geopolitical strategy in Asia much like Putin does American activities in Europe—as containment—he has no illusions about the undesirable consequences of a sudden attack on Taiwan. The Russian invasion of Ukraine not only crystalized those consequences—it has brought America’s Atlantic and Pacific allies together to coordinate global security policy. Xi also understands that from the American perspective, Taiwan is more strategically important than Ukraine. While Biden always made clear the U.S. wouldn’t directly defend Ukraine against an attack, he has not said the same about Taiwan. And unlike Russia’s, China’s economy is strongly dependent on America and its allies. Were China to attack Taiwan, it would risk war with the U.S., devastating economic damage, and sweeping diplomatic isolation—all of which would threaten Xi’s and the Communist Party’s standing. There’s little reason to believe Xi is ready to take that risk—not when he has the option of waiting for the balance of power to swing more in his favor, allowing him to change the political map without firing a shot.

Would a relaxation of U.S. tariffs on China help ease inflation? If so, by how much? (Jason T)

Hundreds of billions of dollars worth of Chinese imports are currently covered by Trump-era tariffs of up to 25%, raising costs for U.S. consumers and firms. Studies estimate that lifting these tariffs would reduce U.S. inflation by about 1 percentage point. That’s modest but meaningful. But tariff easing is looking less likely now, given heightened tensions around Taiwan.

What will happen to China's zero-Covid policy after October? (Joe S)

At best we’ll see only a limited loosening of the policy. Xi Jinping can get away with more flexibility after he’s secured his third term in the fall, but he’s still convinced zero Covid is the right policy on the ground and he’s willing to sacrifice economic growth until China has built a robust stockpile of therapeutics, enough elderly people are vaccinated, and he can be confident that hospitals will be able to handle outbreaks from lifting restrictions. We aren’t close to that right now.

Why are political leaders incapable of thinking about the long-term success of nations and the world? They just seem to create and put out fires. (Sia U)

Political incentives in office (2-4 year terms, term limits, revolving door) are strongly oriented towards the short term. The biggest problem we have right now is people in positions of power maximizing “benefits” in the present while forcing future generations to pay for the costs of our choices. Some discounting of the future and present bias is natural…but control by older generations along with extreme polarization means politicians get whacked hard for “doing the right thing” (i.e., incurring short-term costs for the sake of long-term benefits) and makes incentives truly challenging to align.

If you were a vegetable, which one would you be? (Kim G)

An onion. It makes most dishes more flavorful. And can also make you cry.

What is driving the strength of the U.S. dollar? (Brad F)

Most immediately, Fed tightening (which makes U.S. bonds more attractive) and elevated global risk aversion on the back of the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war (which triggers a flight to safety). The dollar’s status as a safe-haven currency means investors flock to it whenever global turmoil roils markets. In turn, this status is underpinned by the comparative strength of the U.S. economy and institutions. Currencies have to be seen relative to the alternatives. Europe is in a lot more trouble growth-wise and in terms of geopolitical risks, and it lacks a true capital markets, banking, fiscal, and political union. China has huge governance issues and growth challenges, and its currency isn’t even fully convertible. And don’t get me started on crypto…

How does Macron's bid to nationalize EDF play into Europe's energy crisis and NATO goals? (Miguel R)

The plan was always in the cards so it’s not directly related to the war in Ukraine. EDF is in a big mess financially, and Macron has long wanted to remove the small-market element and bring it under political control so that policies like domestic energy subsidies can be more easily imposed. That said, the energy industry took the nationalization as good news, as the government cash is badly needed to raise EDF’s nuclear power output ahead of the expected winter gas shortages. If anything, the war has made the nationalization politically easier to sell.

Given the prospect of massive gas shortages for Europe in the winter, how do you assess the European will to continue providing assistance to Ukraine? (Eric C)

Europe as a whole will remain publicly committed to Ukraine, but disagreements between Germany, France and Italy on one side and Poland, the Baltics and the Nordics on the other will mean a tapering of sanctions and military support this year and next. That doesn't mean no more sanctions or weapons—the EU will continue to climb to the top of its sanctions ladder by end-2023, and Ukraine’s EU candidacy means Europeans accept this war as a European war. So long as the U.S. remains on board, the EU will not fundamentally step back from its commitment to Ukraine. But there’s no doubt that additional measures will be harder to agree in the winter.

Can Europe import enough natural gas from other countries so that it will never be dependent upon Russia again? (Mark B)

It’s not just about importing natural gas from other countries. It’s also about increasing efficiency, improving stockpile capacity in warmer months, extending the lives of nuclear plants, switching from gas to oil usage for industry where possible… and diversifying supply sources. Put all of that together—which the Europeans are doing as fast as they can—and this winter will be the peak of Russia dependency. By the second half of 2023, Europe will have almost entirely and irreversibly weaned itself off Russian gas. Which is why the Kremlin is ramping up its pressure campaign now—Putin knows he won’t have that leverage going forward.

What are the implications of the grain deal for Russia? (Frank H)

It gives them a legal source of revenue (albeit marginal) and makes it easier for them to maintain better relations with poor countries around the world that are taking it in the teeth from food inflation. Worth it on balance, I’d say—for everyone.

Putin says food inflation is mainly the West’s fault. What say you? (@ElonUnplugged)

Putin lies like a rug (a phrase that really doesn’t translate into Russian). None of this would have happened if he hadn’t invaded Ukraine. The West didn’t force him to do that.

How is Biden's “pivot to Asia” going? (Jon L)

Better—in large part because it’s become less of a pivot and more of a coordinated shift among all U.S. allies. Biden actively deprioritized the Middle East—withdrawing from Afghanistan and “recalibrating” the relationship with Saudi Arabia—in favor of the Indo-Pacific. The Russia-Ukraine war then facilitated a broader alignment between the U.S. and its Asian/Indo-Pacific allies on global security concerns, especially in relation to China. The pivot is no longer a matter of leaving traditional allies like the Europeans behind, but rather it’s about bringing all U.S. allies together. But the effort is incomplete because the United States doesn’t have a global trade policy to compete with China’s, meaning it has to focus primarily on security cooperation arrangements like the Quad. That approach is useful but has limited effectiveness.

Will the Dems hold the Senate in January 2023? (Timothy B)

It’s close to 50/50. Given inflation, consumer sentiment, and Biden’s approval rating, Republicans should have this in the bag. But Trump-aligned candidates who’ll be especially vulnerable in general elections have won GOP primaries in several states. And abortion has turned out to be an important issue in some key races post-Dobbs. Remember, the GOP would be holding the Senate right now if it wasn’t for Trump saying the 2020 contest was rigged and depressing turnout in the Georgia special election…

How has your assessment of the risks associated with the U.S. midterms changed since Eurasia Group's Top Risks report came out, if at all? (Vincent C)

To remind readers, risk #3 of our 2022 Top Risks report predicted that the midterms will take place amid allegations of fraud by both Democrats and Republicans, setting up either a “broken” or a “stolen” election in 2024. Since then, there’s been a few developments that marginally lower the odds of this happening. For starters, congressional redistricting turned out to be a wash for both Democrats and Republicans, with Democratic gerrymanders canceling out much of the GOP advantage, courts overturning illegal gerrymanders in several states, and the number of swing seats declining. And the bipartisan reforms to the Electoral Count Act will make it harder to steal an election through alternate electors. At the same time, this effect is blunted by 2020 deniers potentially taking control of election oversight in several states, including Michigan, Arizona, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. Plus, the FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago might make it politically harder for McConnell to let ECA reform pass the Senate. Overall, the risk to the system is still very serious.

Can Moose defuse the culture war? (David L)

At the margins, sure. Whatever your political orientation, it’s hard not to love Moose. He feels the same way about you, by the way.

Do you think that lobbying and disinformation campaigns designed to climate action by the oil, gas and car industry should be seen to be as serious as an act of terrorism? Why do you think our governments appear to be so powerless to stop companies from protecting their interests in these ways? (Stuart K)

Terrorism is a strong word. But the capture of regulatory and legislative power by the private sector is a failing of the U.S. political system. You have to blame executive authority, judicial actors, and lawmakers at least as much as the private sector, because they’re the ones who are supposed to represent the public interest, and they have allowed the system to deteriorate to this point. That said, I’m increasingly upbeat about the anti-climate action lobby because the power of the oil/gas/ICE automaker industries is decreasing dramatically compared to decades ago. By 2050, global fossil fuel production will be dominated by national oil companies, probably including in the U.S. (since it’s hard to imagine high levels of private sector fossil fuel profitability continuing that long).

What looks worse 6 months from now: The economic bubble in China, the energy crisis in Europe, the political crisis in America, the food crisis caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, or the mystery box of eventual overlooked disasters caused by climate change? (@RandomMinutia)

I’ll go with the energy crisis in Europe, followed by the economic bubble in China. Mostly because of timing: this winter is Russia’s point of maximum leverage against the EU, before they fully decouple from Russian energy. And China will have trouble reducing risks in the property market while avoiding crisis given the downturn from zero Covid and slowing growth.

Why don’t you use capital letters or full stops and question marks in your social media posts? (Jarkko L)

My issue is really with capital letters. It’s much easier and faster to type without them. And more importantly, it’s exactly the opposite of people who decide to post with ALL CAPS. Which I’m sure you can appreciate.

As an analyst, how do you de-bias your thought process? (Naren N)

One easy way is to surround myself and regularly work with other analysts from all over the world, with different backgrounds/areas of expertise. It’s also important to travel around the world and follow people/consume media from very different perspectives. The hardest thing to do but one of the most essential is to constantly ask myself challenging questions about the assumptions that underpin my analyses. How could I possibly be wrong? That can’t be a rhetorical question. 😊

Is there any hope for the Red Sox this season? (Alison S)

Next year! But there's plenty of joy in watching. Decades of my youth misspent cheering a never-gonna-win team…

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.