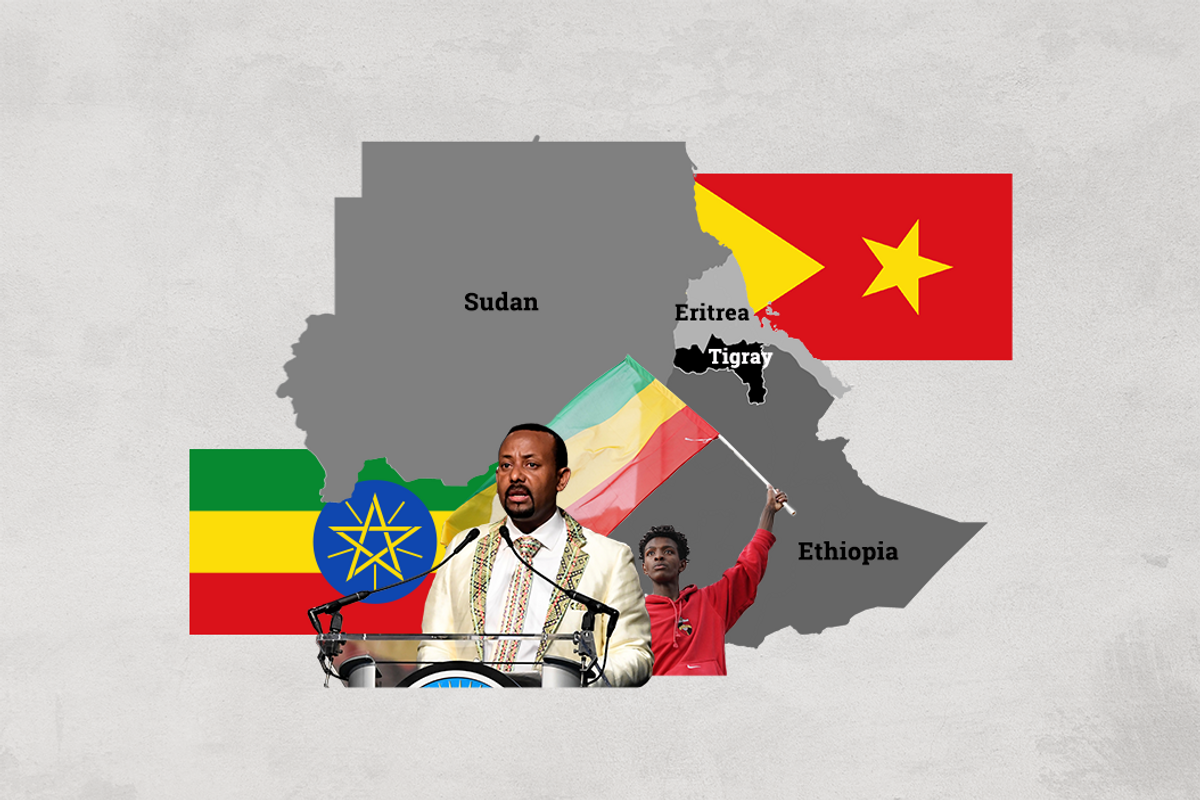

In 2019, Ethiopia's fresh Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed accepted a Nobel Peace Prize for his role in brokering a peace treaty with neighbor and longtime foe Eritrea. At the time, Abiy was hailed by the Western media as a reformist who was steering Ethiopia, long dominated by ethnic strife and dictatorial rule, into a new democratic era.

But barely two years later, Abiy stands accused of overseeing a campaign of ethnic cleansing in the northern Tigray region, putting the country on the brink of civil war.

It's against this backdrop that Ethiopians will head to the polls on June 21 for a parliamentary election now regarded as a referendum on Abiy's leadership. But will the vote be free and fair, and will the outcome actually reflect the will of the people? Most analysts say the answer is a resounding "no" on both fronts.

How did we get here? Ethiopia is deeply fragmented, made up of more than 90 ethnic groups, many of whom have traditionally felt excluded from political power.

Despite accounting for just 7 percent of Ethiopia's population, the Tigray ethnic group dominated Ethiopian politics for decades, after a coalition led by the nationalist Tigray People's Liberation Front helped end the brutal reign of Soviet-backed dictator Haile Mengistu in 1991.

While Tigrayan leader Meles Zenawi, who led the country for twenty years thereafter, oversaw a period of profound economic growth, his was also considered one of Africa's most repressive governments.

Then came Abiy, an ethnic Oromo who when tapped to take power in 2018, pledged to reform a political system that left many Ethiopians feeling marginalized. Abiy promptly released political prisoners from jail, called for exiled Ethiopians to return home, and prioritized press freedom. But in ushering in these reforms, and others, the new PM unhatched the lid on deep-rooted ethnic tensions simmering beneath the surface. Soon after, inter-ethnic resentments boiled over.

Last November, in response to an alleged TPLF attack on an Ethiopian military base, Abiy launched a military offensive in Tigray. The aggressive move was broadly interpreted as comeuppance for Tigray holding regional elections, defying an order from Addis Ababa calling for polls to be stalled amid the pandemic. Abiy, for his part, said it was a response to "treasonous" provocations from the TPLF.

Worsening humanitarian crisis. The military offensive has since escalated into a full blown humanitarian crisis. Many analysts say that Abiy has overseen a campaign of "ethnic cleansing," where Ethiopian troops — backed by Eritrean forces — have brutalized Tigrayan communities; reports of massacres, rapes, and pillaging are well-substantiated. The UN says that at least 350,000 Tigrayans are experiencing famine-like conditions because Ethiopian troops have burned crops, killed livestock, and blocked humanitarian aid. Meanwhile, tens of thousands have been forced to flee to neighboring Sudan, and more than 2.2 million have been displaced.

What does all this mean for the upcoming vote? Abiy was tapped to lead the ruling coalition following the surprise resignation of his predecessor in 2018, so he has long sought a popular vote to earn real legitimacy. Domestically, this validation is particularly important given that Abiy is the first Oromo, Ethiopia's largest ethnic group, to ever serve as prime minister.

But now, many regions will not be participating in next week's vote, citing administrative and security issues. Meanwhile, several political parties, like the Oromo Federalist Congress, are boycotting the election due to a government crackdown on opposition parties in recent months. In total, at least 78 constituencies of the 547 represented in Ethiopia's parliament will not vote on June 21. So even if Abiy wins, it won't be the indisputable victory he wanted.

Unraveling. Despite all its shortcomings, Ethiopia has been deemed a beacon of stability in the chronically volatile Horn of Africa in recent decades, transforming its agricultural and economic sectors to become the third-fastest growing country in the world from 2000-2016.

But as violence persists, there seems to be no end in sight. The TPLF, resentful that it no longer calls the shots in Addis Ababa, has very little to lose, and Abiy has made it clear that he's not backing down either. This threatens not only the stability of Ethiopia, but of the entire region.