Canada’s Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly told the United Nations General Assembly on Monday that Ottawa supports the creation of a Palestinian state and will officially recognize such an entity “at the time most conducive to building a lasting peace and not necessarily as the last step of a negotiated process.”

For more than 70 years, Canada and the United States have been in lockstep on policy in the Middle East. But Canada has been indicating for some time that it is preparing to join countries like Spain, Norway, and Ireland in unilaterally recognizing Palestinian statehood.

Despite pressures from within the Democratic caucus, that is not the position of the Biden administration. President Joe Biden has said he believes a Palestinian state should be realized through direct negotiations between the parties, not through unilateral recognition.

An early 20th-century Canadian cabinet minister, Sir Clifford Sifton, once said the main business of Canadian foreign policy is to remain friendly with the Americans while preserving the country’s self-respect.

That friendship has been tested in recent times.

Last December, Canada voted in favor of a cease-fire in Gaza that did not condemn, or even mention, Hamas. The US voted against the resolution.

For two decades, Canada has voted against UN resolutions that it felt unfairly sought to isolate Israel. Yet in May, it abstained on one that proposed to upgrade Palestine’s rights at the UN to a level short of full membership. Again, the US was one of only nine countries that voted against it.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has criticized his Israeli counterpart Benjamin Netanyahu’s opposition to a future two-state solution – a frustration shared by the Biden administration. But Canada has gone a step further by saying that the peace process cannot indefinitely delay the creation of a Palestinian state.

Tensions were heightened in August when Joly announced new restrictions on the sale of defense equipment to Israel, suspending 30 export permits and blocking a deal to sell Quebec-made munitions to the US that were intended for Israel.

The move drew the ire of Netanyahu, who said it was unfortunate Joly took the steps she did as anti-Israel riots were taking place in Canadian cities.

It also attracted the attention of Sen. James Risch, the ranking member of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. “It is disappointing to see our allies make domestic political decisions intended to hamstring our shared ally, Israel,” he wrote on X.

Graeme Thompson, a senior analyst at Eurasia Group, and a former policy analyst at Canada’s Global Affairs department, said Risch’s comments reflect a “habitual disappointment” about Canadian foreign policy in Washington.

“By now, expectations are so low that it is hard to be disappointed by anything. People have come to the conclusion that Canadian foreign policy is about grandstanding and domestic politics, rather than national interests,” he said.

Risch was one of 23 bipartisan senators who wrote to Trudeau before the prime minister traveled to Washington for NATO’s summit in July saying they were “concerned and profoundly disappointed that Canada’s most recent (military spending) projection indicated it will not reach the 2 percent commitment this decade.”

At the summit, Canada’s ambassador in Washington, Kristen Hillman, said there remains “a strong recognition that Canada is a steadfast ally in all aspects.” But that rosy view was not reflected in the comments made by US policymakers. House Speaker Mike Johnson described Canada’s promise to get to 1.76% of GDP on defense spending by 2030 as “shameful.” “Talk about riding on American coattails,” he said.

Even Biden’s extremely discreet ambassador in Ottawa, David Cohen, referred to Canada as “the outlier” in the alliance.

Eurasia Group’s Thompson agreed with Risch’s assessment that domestic politics are at the root of a shift in foreign policy that moves away from traditional support for Israel and does not view security spending as a priority.

He said the debate in the ruling Liberal Party is similar to the one playing out in the Democratic Party in the US – but is at a more advanced stage because it has the blessing of the leader, Trudeau.

He noted the base of support for the Liberals has moved from ridings with large Jewish populations in Toronto and Montreal to ridings with large Muslim populations in the suburbs of both big cities. Trudeau has tried to walk a fine line between both communities, often failing to please either of them.

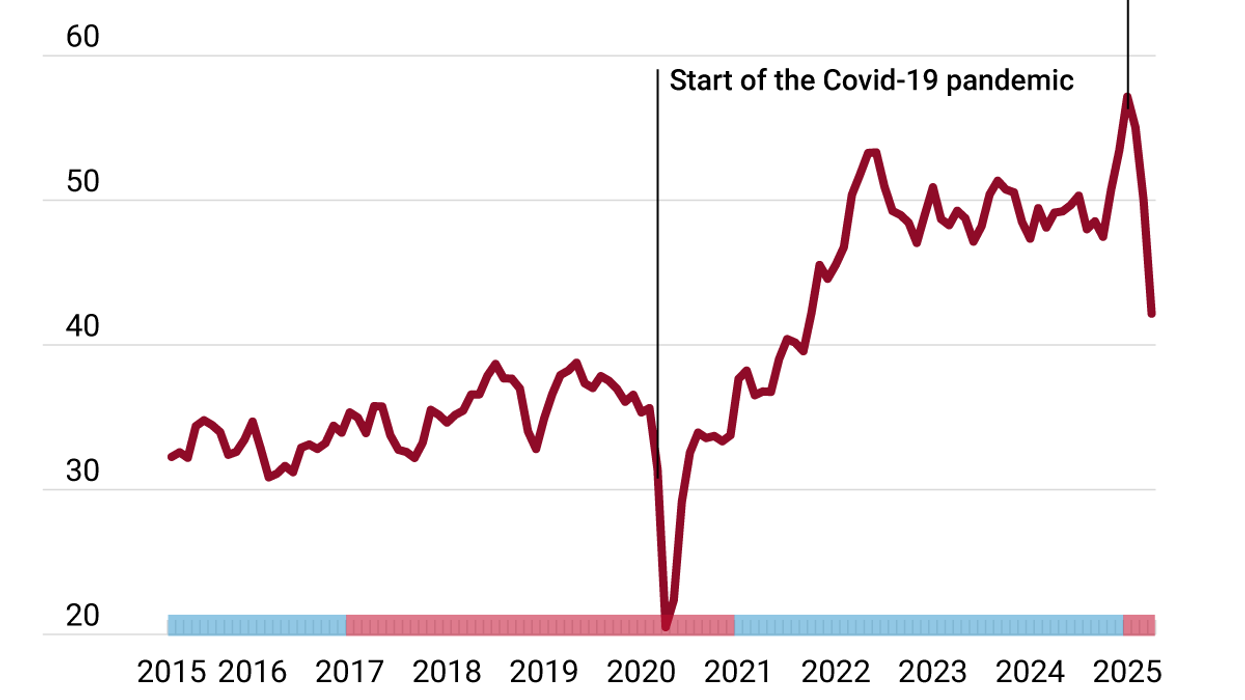

His Liberals are trailing the Conservatives by around 20 points in most polls, and the opposition party leader, Pierre Poilievre, is pushing for a general election.

The Liberals are relying on the support of the left-leaning New Democratic Party and separatist Bloc Québecois to keep them in power. Both of those parties are highly critical of Israel and strongly supportive of a Palestinian state.

A debate in the Canadian House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee on the recognition of a Palestinian state last week reflected the realignment of foreign policy. The committee voted in favor of a short study, after which a recommendation to unilaterally recognize a Palestinian state will likely be made to the government. The Liberals on the committee voted alongside the NDP and the Bloc, arguing that for a two-state solution, you need two states.

The Conservative foreign affairs critic, Michael Chong, said that unilateral recognition would break with the long-standing position of the successive Canadian governments and would isolate Canada from its allies, including the US.

“To veer from that path rewards violence and authoritarianism,” he said.

The committee vote has not yet drawn a response from Washington.

That does not surprise Derek Burney, a veteran Canadian diplomat who served as Ottawa’s ambassador in Washington from 1989 to 1993.

He said Canada’s view has become inconsequential to its allies. “I’ve never seen a time when we were more irrelevant than we are now. We are nowhere on the global scene. We are nowhere in Washington because we have nothing to contribute or to support what the Americans are trying to do,” he said.

“Nobody knows what we stand for, or stand against. We don’t count. It’s a sad fact of life.”