Fresh out of Barnard College with a degree in political science, Riley is a writer and reporter for GZERO. When she isn’t writing about global politics, you can find her making GZERO’s crossword puzzles, conducting research on American politics, or persisting in her lifelong quest to learn French. Riley spends her time outside of work grilling, dancing, and wearing many hats (both literally and figuratively).

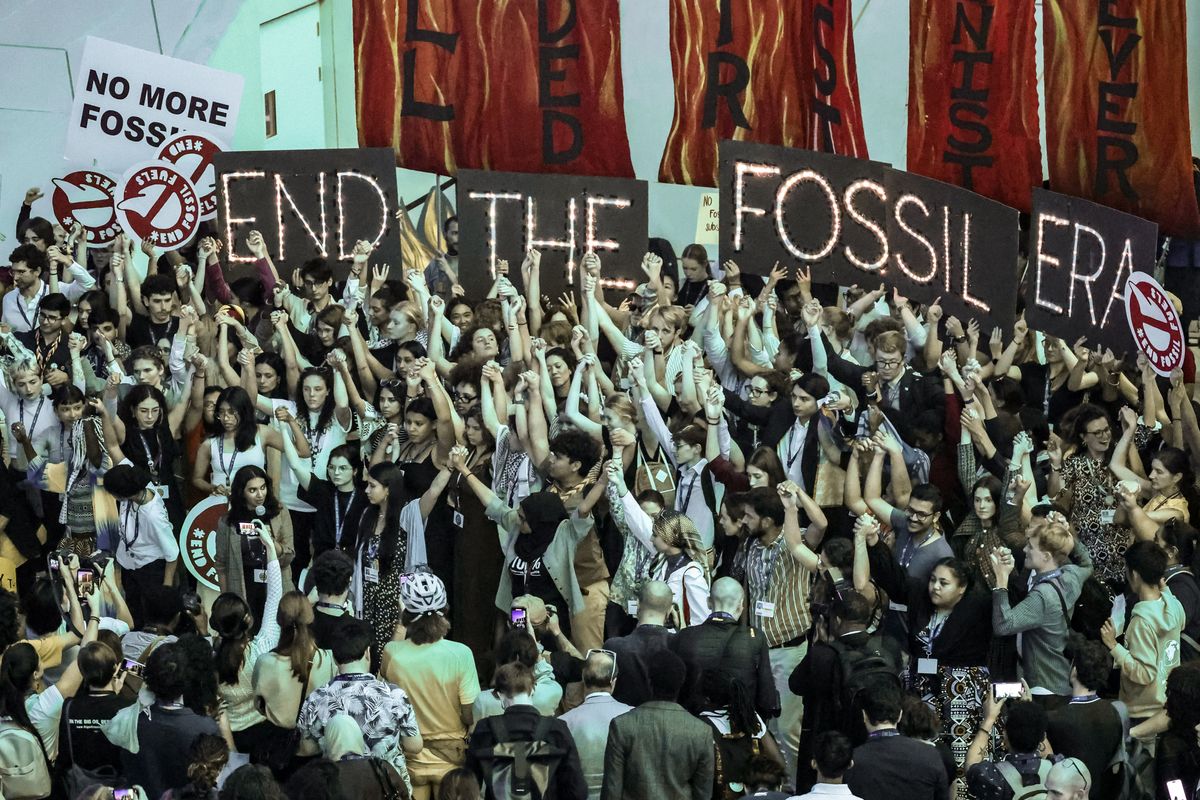

It was a chaotic COP28, to say the least. But after 28 years of climate negotiations, on Wednesday representatives from nearly 200 countries signed an agreement to transition away from fossil fuels.

The agreement contains much stronger language on fossil fuels compared to a previous proposal, which said nations “could” take actions to slash greenhouse gas emissions, giving fossil fuel-producing countries – including COP28’s host, the United Arab Emirates – the option to not give up the Golden Goose.

President Sultan al-Jaber, an Emirati oil company executive leading the talks, gavelled in approval of this earlier version on Wednesday morning without giving critics a chance to speak, and when representatives of small island nations – who have been outspoken that they “will not go silently to [their] watery graves'' – were not present. Al-Jaber’s statement that there was “no science” to support a phaseout sparked an uproar, sending the conference into overtime.

The US and Canada joined forces with small island nations to insist that a fossil fuel phaseout make it into the agreement. In the end, the countries compromised to “transition away” from fossil fuels. This is the first time the root cause of the climate crisis has been stated in a decision in nearly 30 years of environment talks.

But critics say the final document contains “a litany of loopholes.” Fossil fuels are just called “transitional fuels” and are condoned to “facilitate the energy transition.” It legitimizes gas burning on the basis that it is less polluting than coal, though liquefied natural gas may be worse than coal due to methane leaks.

After a year of devastating natural disasters, Canada came to the conference as the only major oil-producing country to implement an emissions cap. Ottawa also announced the world’s most ambitious methane regulations it claims will lead to emissions reductions of at least 75% by 2030. It is also the first G20 nation to phase out fossil fuel subsidies, two years ahead of the deadline.

Meanwhile, the US had less to be proud of. While the Inflation Reduction Act marked the most aggressive climate investment in US history, oil and gas production is at record highs, and it is planning continued expansion, especially in LNG.

Talk is cheap. The agreement called for a tripling of renewable energy by 2030. But whether that can happen depends on how much money is offered for emerging economies and low-income countries, and how soon. All details are left for next year's COP, which will be hosted by Azerbaijan, another petrostate. However, a $700 million fund was formally established to offer money to countries that have suffered irreparable economic losses and damages, and the World Bank and the IMF were called upon to expedite loans for energy projects in developing countries.

A key test for national governments will come in 2025, when every country is expected to set its next round of climate targets. COP30 is the one to watch, as it will be held in the Brazilian Amazon, a region on the frontlines of the climate change crisis, which is expected to amplify the voices of vulnerable countries.