My political compass has been spinning lately, and not just because Robert F. Kennedy Jr. admitted to ditching a bear corpse in Central Park before finally endorsing Donald J. Trump (that one caused a bit of political vertigo). My deeper confusion stems from the political debate about protecting our jobs.

It used to be, reliably, that the conservative right supported free trade and globalization, while the progressive left wanted protectionism for local industries.

Elections were fought on this, libraries were filled with studies on it.

For Republicans, Ronald Reagan’s 1988 Thanksgiving address was considered economic theology. “One of the key factors behind our nation’s great prosperity is the open trade policy that allows the American people to freely exchange goods and services with free people around the world,” the Gipper said.

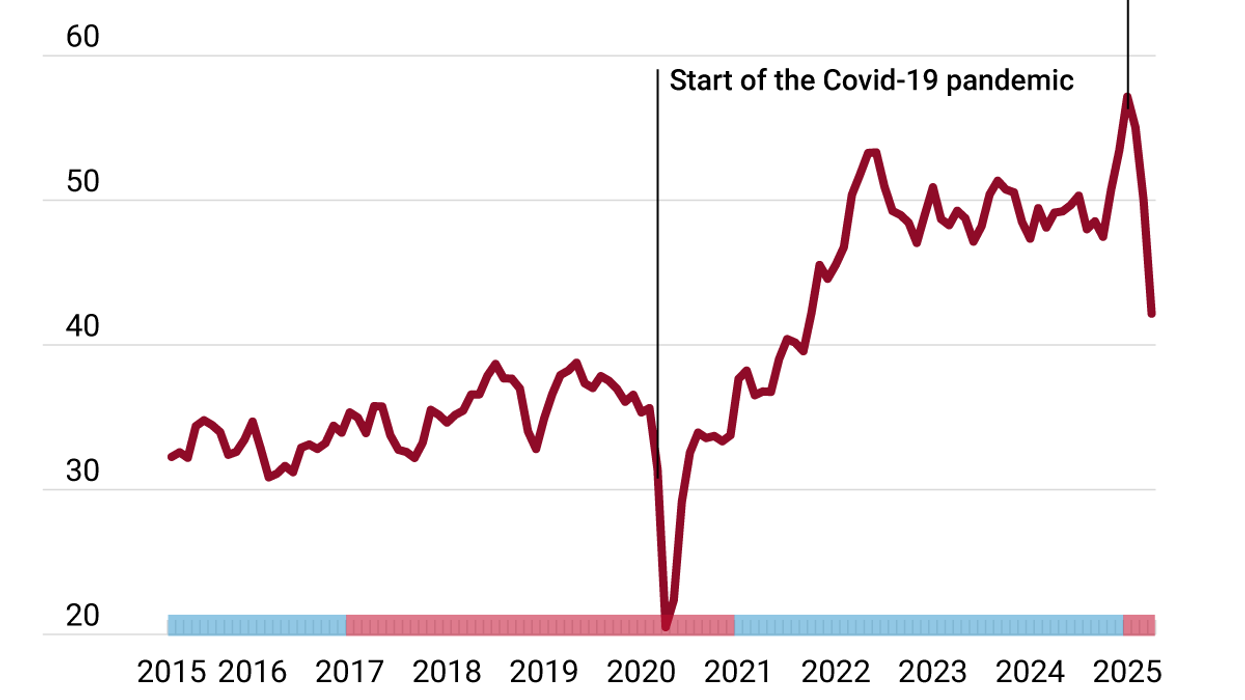

That era ended under Trump’s first administration when he used two tools to impose tariffs on a wide-ranging series of goods: Section 301 (tariffs that combat unfair trade practices) and Section 232 (tariffs that protect national security). These tariffs hit almost $280 billion of goods and, according to the American Action Forum, increased consumer costs by over $51 billion a year. By the way, Joe Biden kept most of these in place. Recently, Biden went even further, slapping $18 billion worth of tariffs on Chinese-produced EVs, semiconductors, and critical minerals, among other things. This is all part of the industrial policy he ushered in under the Inflation Reduction Act. So both sides love a good tariff.

But in this campaign cycle — it’s as if a sequel titled “The Tariffs Strike Back” has been released — we must wonder: Is this the beginning of the end of globalization and the rise of a new age of tariffs?

Both Republicans and Democrats are making tariff-happy promises. Trump has mused on the campaign trail that he would like to impose a 10% tariff on all goods coming into the US.

“When companies come in and they dump their products in the United States, they should pay automatically, let’s say, a 10% tax … I do like the 10% for everybody,” the former president explained.

And it is not just in the US. Tariffs are being used everywhere. This week, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau aligned with the US and announced tariffs on Chinese-made EVs starting Oct. 1, and another 25% tariff on Chinese steel and aluminum.

“Actors like China have chosen to give themselves an unfair advantage in the global marketplace,” Trudeau said, “compromising the security of our critical industries and displacing dedicated Canadian auto and metal workers.”

He’s not wrong. China does have widespread, unfair trading practices. Using tariffs to rebalance against factors like low-wage workers or weak environmental standards is useful, as they can be to deal with trade imbalances. But it’s a slippery slope. Tariffs beget tariffs, and that starts a trade war where everyone loses.

Tariffs were critical to Trump’s first administration, especially as he renegotiated the NAFTA agreement with Mexico and Canada. But economists at places like the CATO Institute concluded that tariffs cost taxpayers anywhere from $50 to $80 billion in higher prices. “American consumers (both firms and individuals), not foreigners, paid for — and continue to pay for — the tariffs,” the experts wrote.

So why are they back? If Trump 1.0 taught politicians across the spectrum anything, it's that there are no votes in supporting globalization. Most states and provinces have lost jobs and plants to cheap labor in places like China and Mexico, and protecting jobs wins elections today, even if it means higher prices tomorrow.

And that’s exactly what it means. According to the Center for American Progress Action Fund, if Trump were to impose the across-the-board 10% tariff, it “would amount to a roughly $1,500 annual tax increase for the typical household, including a $90 tax increase on food, a $90 tax increase on prescription drugs, and a $120 tax increase on oil and petroleum products.” And there is a real debate as to whether higher tariffs, which aim to create jobs, actually do so.

A study from the US Department of Agriculture revealed that Trump’s 2018 tariffs on major trading partners like China, Canada, and Mexico cost billions due to retaliation. “From mid-2018 to the end of 2019, this study estimates that retaliatory tariffs caused a reduction of more than $27 billion (or annualized losses of $13.2 billion) in US agricultural exports,” the study said.

This is a case of Hobson’s choice: Keep some manufacturing jobs in your community, but face higher prices, lower productivity, and retaliation from other countries. After all, one tariff begets another, and the costs pile up. But the political gains are real, so protectionism is on the march again.

Trump’s VP running mate, Sen. JD Vance, recently defended tariffs and, to be fair, many countries have massive exceptions to free trade that include cutouts to protect certain industries with subsidies and quotas. In the US, national security is used extensively as a form of industrial policy — Trump, for example, imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, citing national security concerns. And in Canada, banks and milk and cheese farmers in Quebec are protected.

But Vance has gone further, arguing that tariffs in principle are a net economic gain. A tariff “causes this dynamic effect where more jobs come into the country,” Vance recently said on “Meet the Press.” “Anything that you lose on the tariff from the perspective of the consumer, you gain in higher wages, so you’re ultimately much better off. You have more take-home pay, you have better jobs,” he added.

By that logic, more tariffs would keep growing the economy, so where will they stop? That is the road to end any form of free trade and globalization.

Strangely, Vance’s argument not only flies against the conventional wisdom of his own party — the GOP has long advocated for free trade and open markets — but it also parrots what the left argued for decades as they fought free trade and globalization even as they were ridiculed by people like Reagan.

During Trump’s first term, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation published a piece called “Is the GOP Still the Party of Free Trade?” and concluded that they are not, especially after Trump took the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. That was a multilateral trade agreement with Asian countries meant to keep a strong US presence in Asia as a hedge against China. While 191 Republicans originally voted for it, that Republican Party no longer exists. “The effective abandonment of its free trade credentials sets the Republican Party on a perilous path,” wrote Phil Levy of the Reagan Foundation.

Democrats must be delighted that an argument they once lost so publicly is being relitigated. Now, both sides are arguing for the same thing and trying to outdo each other. It will be interesting to hear what Kamala Harris says about this as she finally reveals some policy.

We have now gone from embracing concepts like “nearshoring” and “friendshoring” for critical supply chain products like medicine and AI chips to picking winners and losers across the economy. This is 1970s industrial policy, and the distinction between the left and the right on this has become minimal.

Is this how globalization dies, one tariff at a time, in a series of trade wars and spats, Brexits and exits, until finally, the trade walls are back up, productivity plummets, and prices rise? Or is there a happy medium, where these global fights lead to a rise in both labor and environmental standards in places like China and Mexico and the cliched expression “fair trade, not free trade” actually becomes a reality?

Either way, it won’t be quick and, in the meantime, brace yourself for higher prices as your political compass keeps spinning wildly out of control.