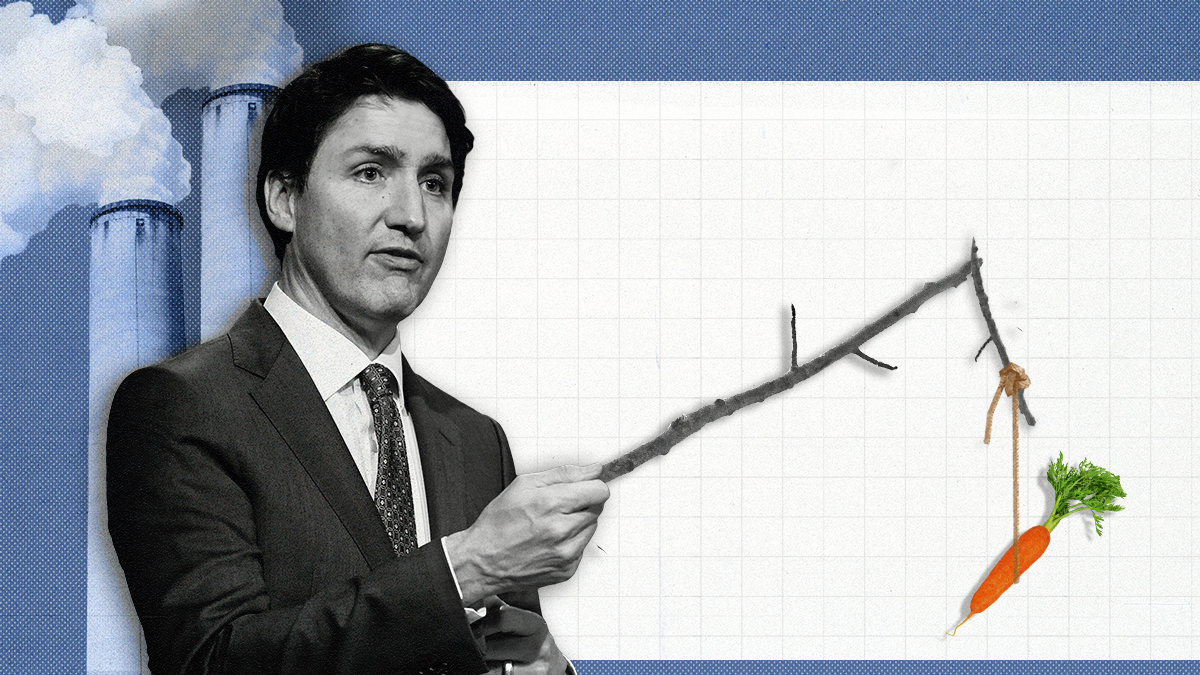

After years of staring down opponents to his national carbon tax – which puts a price on emissions and sends taxpayers rebates as a way of encouraging the reduction of climate-harming pollution – Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has finally blinked, putting his whole emission-reduction plan in jeopardy. The move raises questions about whether it’s possible to use carrots and sticks to change voter behavior.

The problem started a month ago when a Liberal party member of Parliament from rural Newfoundland voted with the Conservative opposition for a motion to repeal the carbon tax. Turns out, voters in Canada’s rural Atlantic region, many of whom heat their homes with oil, have been letting their representatives know that they don’t appreciate the extra cost of the tax, which comes on top of higher global oil prices. They want carrots, not sticks, from environmental policies.

Ken McDonald, the MP for the riding of Avalon, voted with his people instead of his government. “Everywhere I go, people come up to me and say ... 'We're losing faith in the Liberal party,” he said.

Atlantic voters have been reliable Liberal voters since Trudeau was first elected in 2015, but the polls show support in the region collapsing, putting withering pressure on his MPs. So last week, Trudeau backed down, announcing a three-year pause on the application of the carbon tax to fuel oil, which came as a huge relief to his Atlantic MPs, but not to people in other parts of the country, who heat their homes with cleaner natural gas.

Axing the tax

Trudeau saved himself some pain in one part of the country, but he has undercut the arguments for the tax. His government has always insisted that most people get bigger rebates than it is costing them, but he has now acknowledged it is causing hardship for some, opening the door to similar complaints. It looks like political favoritism. In fact, one of his own ministers gave an interview saying that if Westerners want their fuel tax cut, “perhaps they need to elect more Liberals.”

Strangely enough, Westerners have not welcomed that message, and people in the rest of the country are crying foul. Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe is so upset that he has threatened to stop remitting carbon tax charged on natural gas.

Meanwhile, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre is poised to benefit, since he has made getting rid of the carbon tax the centerpiece of his leadership, holding well-attended “Axe the Tax” rallies in rural Canada, where resistance to the tax is greater than in cities. Poilievre has enjoyed a double-digit lead over the Liberals for months.

“This is not going to convince anybody who was gonna vote for Poilievre because they didn't like the carbon tax to come back,” says Graeme Thompson, a global macro-geopolitics analyst with Eurasia Group. “But they also now risk alienating some of their supporters, maybe more in the center and on the left, who really support action on climate change. I wonder if they've kind of just opened up a bit of a two-front war.”

Not only in Canada

As voters face cost-of-living pressure around the world, politicians are under growing pressure to back away from emission-reduction measures. In September, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak postponed measures designed to bring Britain to net zero by 2050.

But Canada is facing a unique challenge because of US President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which is providing huge subsidies to green-tech projects. This provides an opportunity for the Conservatives, who can campaign on dropping Trudeau’s carbon tax and adopting Biden’s plan by subsidizing green projects, says Thompson.

“Take the Biden policy, make it the Conservative policy, say, ‘We’re going to incentivize investment. We're going to incentivize energy production. That’s going to produce jobs. We’re going to get growth, and we’re going to eliminate the carbon tax, and there’s our platform.’”

A problem of design

The Trudeau government has promised there will be no more carve-outs, but the pressure will not stop. Environmentalists are disappointed that Trudeau backed down. Tim Gray, executive director at Environmental Defence in Toronto, worries that the design of Canada’s carbon tax makes it hard to sustain politically because voters notice the increase in their fuel bills and tend not to notice the rebates.

“The way that the carbon pricing system in Canada was designed at the retail level gives you the worst way to go forward in terms of building political support, based on our experience and knowledge of where people arrive on these kinds of issues.”

When he announced the three-year pause, he also announced an Atlantic pilot project for heat pump rebates. Gray thinks the government should have done more of that and paid for it by taking money from the oil companies profiting from the high prices.

“It would have been better to pair deeper investments in fossil fuel transition — not just for oil but also natural gas, etc. — with a windfall profits tax on the oil and gas industry because it’s a narrative that is easily explained.”

Trudeau’s carbon tax is one of the government’s signature accomplishments, which enjoyed wide support from environmentalists and climate-conscious voters, a political message that he managed to sell in three election campaigns and that his lawyers successfully fought for in court cases.

But it is starting to look like using sticks as well as carrots to bring down emissions is not going to work, and Canada may eventually be forced to match the American policy, which is all carrot and no stick.