Between now and the fall of 2025, both the United States and Canada will hold general elections with the incumbents up against the odds. President Joe Biden is in a tough reelection campaign against former President Donald Trump. It doesn’t help that calls for Biden to step aside are mounting, casting doubt on his capacity to run and serve another four-year term.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is also facing calls to stand down — a former cabinet minister has said it’s time for him to go, as has a member of his caucus and at least three former Liberal MPs. Meanwhile, there are rumblings that some incumbents might bail on the next election, and there’s a significant chance that MPs, current or former, are keeping their true feelings to themselves, at least for now.

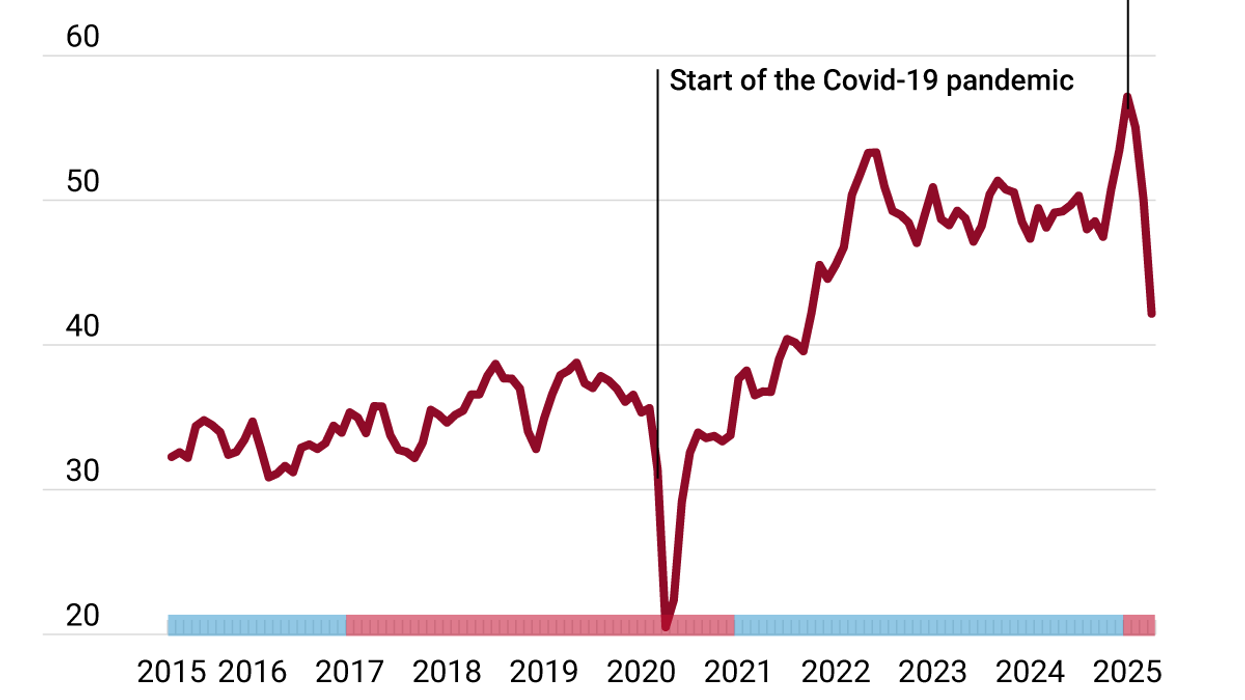

Trudeau’s Liberals trail their Conservative opponents by double digits, with some polls putting them 20 or more points behind.

With the drama of electoral uncertainty and breathless media coverage, these contests can sometimes look more like reality television than high-stakes democratic exercises. The horse race coverage of polls doesn’t help. Individual polls get reported as final words, definitive predictions of what will happen. But single polls are snapshots in time, subject to margins of error and the risk of being an outlier or of not telling the whole story.

But there’s a better way to predict election outcomes: projections. Made up of an aggregate of polls and complementary data, such as electoral history, current trends, and even economic data, projections give observers a broader sense of what’s going on in a race and what’s likely to happen. Of course, projections aren’t crystal balls — things can change, and campaigns can and do make a difference. But good data interpreted properly can give us a good sense of the likely result.

Canada and the US have various election projection resources, with 338 Canada, run by poll analyst Philippe Fournier, the mainstay up north, while Nate Silver’s 538 is a go-to in the US.

In the case of 338, Fournier is projecting bad news for Trudeau and Biden. As of this week, the site gives the Conservatives a greater than 99% chance of winning the most seats in the next Canadian election and a 99% chance of winning a majority government with a range of between 179 and 234 seats.

It also gives Trump a 69% chance of winning, taking 312 electoral college votes to Biden’s 226. That stands in stark contrast to 538, which, as of writing, features a simulation projecting Trump edging out Biden 271 to 267.

For his work on elections in Canada, Fournier’s methodology relies on weighted polls and draws on demographic data that includes age distribution, education level, population density, and immigration level riding-by-riding. Fournier notes that the data he draws on is available through the census and from Statistics Canada. His model for the US presidential race, however, is comparatively pared down, going state by state, drawing on polls and past results, and relying far less on demographic data.

The 2024 presidential election model at 538 uses polls, but it also adjusts its predictions by “correcting” poll bumps around convention time, connecting and correlating poll movements across states. “If President Joe Biden improves his standing in Nevada,” as 538’s G. Elliott Morris explains, “our forecast will also expect him to be polling better in states such as Arizona and New Mexico, which have similar demographics and are part of the same political region.”

Fournier and 338 have a solid record of correct predictions. In 13 general elections in Canada, federal and provincial, covering over 1,600 individual districts, 338 has managed to pick the winner 90% of the time, while 6% of their misses were within the margin of error. In an enterprise marked by the uncertainty of human behavior, and with countless data available, being accurate 9 out of 10 times is impressive. In the 2020 US election, Fournier correctly projected 48 of the 50 states.

Projections are powerful, but they aren’t oracles. In the context of the US presidential race, Noah Daponte-Smith, an analyst at Eurasia Group, says, “No forecast should be taken as definitive, especially five months out from the election.”

Daponte-Smith also points out that since different projection models rely on different methodologies and data — how they weight individual polls, which (if any) economic indicators they use, or how they manage polling error — their results may diverge from one another.

“These differing sets of assumptions mean that it is possible the forecasts move in opposite directions at some point in the race, potentially if polls are pointing in one direction while economic fundamentals are pointing in another,” he says.

The data, on aggregate, doesn’t tend to lie. But it has to be chosen, collected, and interpreted, and not all collection and interpretation is created equally. Fournier says that social media, right now, is “flooded with amateurs with spreadsheets.” Often, he says, election watchers will model a simple poll and draw conclusions, which he doesn’t do since there’s so much uncertainty from poll to poll.

“Using only one poll at the time, and projecting one poll at a time,” he says, “would be like rolling in the streets of Montreal or Ottawa without shock absorbers. You need shock absorbers. If a poll says, let's say, the Liberals are at 25 and the others say they’re at 20 a day later, they haven't lost five points in a day; they're somewhere between 22 and 23.”

By the time you aggregate polls — add the shock absorbers — you start to get a good picture of what’s likely to happen. The trick to understanding projections is to keep in mind that they’re probabilistic, which means they deal in probabilities, not certainties. As Fournier points out, “When you say that a candidate has a 90% chance to win, it sounds overwhelming. It sounds like, ‘Oh, it’s in the bag.’ But it also means that there’s a 10% chance that he doesn’t win, and 10% is 1 out of 10.”

A 1-in-10 chance might not sound like a lot, but imagine if you were told there’s a 10% chance that you’ll suddenly lose your life savings one day. Or drop dead. You’d quickly appreciate how significant small chances can be. Indeed, much of the US was reminded of that lesson in 2016 by watching the New York Times’ probability needle, which pointed to a probable Hillary Clinton win, until it didn’t.

While the Canadian election race isn’t close, the US contest is much closer. Fournier says that the large electoral vote lead he has projected for Trump is built on Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania historically voting as a bloc, stretching back to the 1988 presidential election, and currently sitting as a toss-up that Biden must win to have a chance.

“It’s still a very close race,” he says. Nonetheless, “The favorite right now, undoubtedly, is Trump with the numbers that we have.”