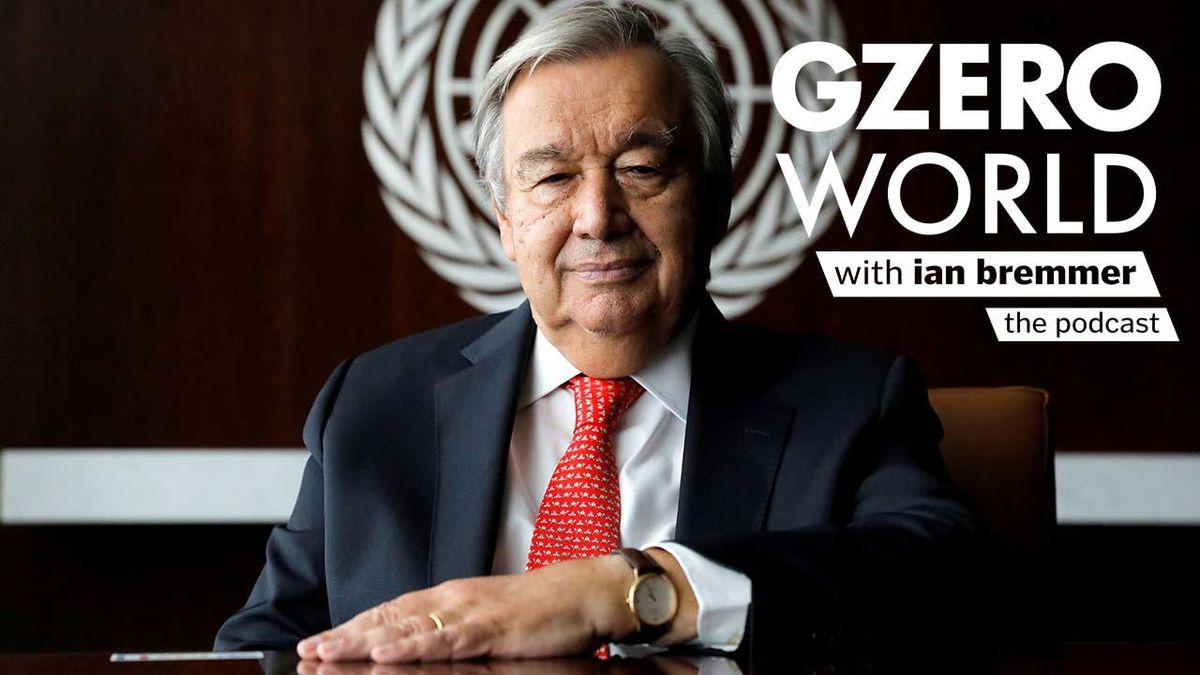

TRANSCRIPT: UN Sec-Gen Guterres has a warning for disunited nations

António Guterres:

We are on the verge of the abyss. And one thing it is clear. If you are on the verge of an abyss, you must be careful about your next step.

Ian Bremmer:

Hello and welcome to the GZERO World Podcast. This is where you can find extended versions of my interviews on public television. I'm Ian Bremmer, and today I am coming to you from the United Nations Global headquarters in New York City as the 76th annual session of the UN General Assembly gets underway.

There were high hopes that with vaccines and proper precautions, this year's summit of global leaders and diplomats will be more or less back to normal. But as you know, the Delta variant had other ideas. And while some world leaders like India's Narendra Modi will be making the trip in person, most will be attending virtually for the second year in a row. They will all however be grappling with the same question, how to rebuild a world that has been hobbled by a year and a half of pandemic? Today, I'm posing that question and many more to UN Secretary General, António Guterres. Here's our conversation.

Speaker 3:

The GZERO World Podcast is brought to you by our founding sponsor, First Republic. First Republic, a private bank and wealth management company, places clients' needs first by providing responsive, relevant, and customized solutions. Visit firstrepublic.com to learn more.

And GZERO World also has a message for you from our friends at Foreign Policy. COVID-19 changed life as we know it. But as the world reopens, this moment also presents an opportunity. On Global Reboot, Foreign Policy looks at old problems in new ways. From US-China relations to gender inequality and racial discrimination, each week, Ravi Agrawal speaks to policy experts and world leaders and thinks through solutions to our world's toughest challenges. Check out Global Reboot wherever you get your podcasts.

Ian Bremmer:

Secretary General, António Guterres, so good to see you again.

António Guterres:

It's a great pleasure to be here.

Ian Bremmer:

As the Secretary General, I mean, you are the man who is most aligned with global leadership, with multilateralism. And so I have to say from my perspective right now, when I look at climate change, when I look at the response to the pandemic, when I look at Afghanistan, it doesn't feel great right now. The trajectory feels pretty bad on all of those issues. How do you respond to that in your position?

António Guterres:

Well, we are facing a number of dramatic challenges. A virus is defeating us as an international community. Climate change, we are far from the consensus that is needed between developed and developing countries to really be able to get to net-zero in 2050. And at the same time, we see this multiplication of crisis all over the world. We are going in the wrong direction in all these aspects.

We see a geopolitical divide that is becoming deeper and deeper. The geopolitical divide today is such that in crucial areas like vaccine equity or climate action, we do not see the international community united, especially because the big powers are not united. The big powers are deeply divided. And this is a dramatic situation.

Now look at COVID. I mean in my country, 80% of the population is vaccinated. Many African countries have 2% of the population vaccinated. We see mutations all the time. We see variants all the time. Now they speak about variants that might be able to be immune to vaccines. So as the COVID is spreading like wildfire in the developing countries, we risk to make the vaccines that are essentially available to develop countries useless. This is a suicide.

Look at climate. When we see what happened in Germany, when we see what happened in Canada with the heatwaves, when we see what's happening with the glaciers in Greenland and the level of the seas rising, when we see Antarctica being put into question, I mean it is clear that we are facing a disaster in climate change. But at the present moment there is a lack of trust between developed countries and developing countries, especially emerging economies. It is clear emerging economies need to be more namely on call. But it is clear developed countries must abide by the commitments they made in Paris, namely to mobilize 100 billion US dollars in support to developing countries, both to reduce emissions and to support their population in resilience, in building better infrastructure, being able to resist these horrible events that climate change is creating.

Now we need to rebuild trust between developed countries and developing countries if we want to rescue COP26. And the worst thing that would happen to us is this mistrust going on, the developed countries not being able to meet their commitments, developing countries, especially emerging economies, not being able to reduce emissions as much as needed. And we will get in some aspects to tipping points.

Ian Bremmer:

So what happened?

António Guterres:

And then it's irreversible.

Ian Bremmer:

What happened? I mean talking specifically about COP26 and your first term as Secretary General has been at least as much about climate as anything else. Biden becomes president. For the first time ever, John Kerry, a cabinet appointee for climate change. He knows the issue. He has the network. The US rejoins Paris Climate Accord. And yet right now everything I hear is that COP26 is actually set up to fail. What happened?

António Guterres:

Well, there was a time in which the fact United States was engaged in a important international issue that would mean that issue could be solved. I remember when I was prime minister in Portugal, the East Timor crisis. The East Timor crisis everybody thought there was no solution. The day-

Ian Bremmer:

And there was US leadership, absolutely.

António Guterres:

The day I was able to convince the President of the United States that an intervention was necessary in East Timor, Clinton made a speech when he was traveling to a meeting of the Pacific. He said that intervention was necessary. The Indonesians immediately accepted, the Australians landed, and the Security Council that one week before considered it impossible made it necessary. This was a time of the US as the hyper power. The fact the US was engaged on an issue would mean that the whole world would become engaged on that issue.

We are no longer in that situation. Today no issue can be solved without United States. And so without United States on climate action, we were doomed. But the fact United States are on climate action is not enough because today the largest emitter is not United States, it's China.

Ian Bremmer:

China.

António Guterres:

And today the emerging economies represent a very large percentage. And the emerging economies, of course, can blame the developed countries saying, "Well, but you have been polluting for decades and decades and now you want us to do an extra effort." And they need to do that extra effort. But to do that extra effort developed countries must show that they also will do what they were supposed to do, namely in financial and technical support to developing countries.

And what we see now is this lack of capacity for a dialogue to come together and to understand that each one needs to give something and everybody ... It's like the chicken and the egg. Now everybody's waiting for the other side. I've been telling our English friends that preside the COP, we need to bring together the G7 on one side, the basic. Basic is Brazil, China, India, South Africa on the other side and create a situation in which both understand that we are in a very, very dangerous situation because there are some tipping points we are very close to which, which means a little bit more time and 1.5 degrees will not be the possibility as maximum increase in the amount of temperature.

Ian Bremmer:

Well, in fact, in your latest report on the common agenda, you say that we will pass two degrees of centigrade warming by 2100.

António Guterres:

If we would keep the national determined contributions, which means the commitments made by states, if we would keep them as they are, we would reach 2.7, 2.9 degrees, which means we are on the verge of the abyss. And one thing it is clear. If you are on the verge of an abyss, you must be careful about your next step. And if COP26 does not become a success, if we are not able to cope with this challenge and finally bring the countries together. And I'm intending to convene here in New York on the 20s a summit of 40 countries in which all the key countries are, and I've been discussing with Mario Draghi on the G20 because all the key countries are in the G20. They represent more than 80% of the-

Ian Bremmer:

Of the emissions-

António Guterres:

... emissions. I mean, we need to make these countries understand this is the moment for an historical compromise. And whatever divisions they have, whatever geostrategic problems they have, whatever completely different visions they have on human rights, the question is it is the survival of humanity, it is the survival of the planet and we need to come together.

Ian Bremmer:

For right now when we talk about climate and the COP26, is it fundamentally a US-China breakdown that's causing the problem?

António Guterres:

No, it's a developed world versus developing and in particular emerging economies, because emerging economies are already too important to be neglected. We need them also to make an extra effort. But for that extra effort to be possible, we must have a lot of support from developed world.

Coal for instance. I've been advocating for no more coal power plants and for the phase out of coal until 2030 for OECD countries, until 2040 for all the other countries. But it's true that several economies are completely dependent on coal, and we need to help them create a transition. And for that they need financial and technical support. But we are not yet there. And what indeed is missing is what I said in the beginning. We need to raise the alarm because world leaders need to wake up. And as you know, it is possible to sleepwalk into a conflict and it is possible to sleepwalk into a disaster in climate.

Ian Bremmer:

And that's what you see happening.

António Guterres:

That is what is happening at the right moment if people will not wake up.

Ian Bremmer:

I mean the IPCC report was probably the most depressing single piece, most depressing single document I had ever seen.

António Guterres:

Depressing.

Ian Bremmer:

Yes.

António Guterres:

But it says we are still on time. Depressing because the consequences that are shown are dramatic and everything is getting worse, even worse than expected. But it says we are still on time. And this is what is important. We can do it. We are still on time. But those that have power need to assume their responsibility.

Ian Bremmer:

Has COVID over the last two years made it more challenging for the climate agenda to move forward?

António Guterres:

To a certain extent, yes, and to a certain extent, no. To a certain extent, yes, because obviously COVID also generated a lot of mistrust between developed and developing countries. I mean, vaccine inequity doesn't help to build trust. The fact that developed countries are today mobilizing about 28% of GDP to recover their economies and they have the resources for that, middle income countries probably about 6% of their GDP, low income countries, probably about 2%, a very small GDP. The fact that we have huge depth problems that are not properly addressed in the developing world, this inequity in relation to vaccines and in relation to recovery doesn't help to build trust.

So obviously the COVID has created an environment that has not facilitate the countries coming together because they didn't come together effectively on the COVID. But at the same time, the COVID demonstrated our enormous fragility. I mean it's a virus that is defeating ... We are more than one year and a half after it started. And look at United States, it's getting worse again. I mean this is almost unimaginable. You have one wave, another wave, a third wave.

I mean we are extremely fragile as a planet and the societies. And we have many other problems in our societies as we know, mistrust between people and institutions, all the problems the democratic societies are facing. Many talk about the end of truth. The scientific evidence is being put into question. So we have plenty of problems. But at least, I mean it is clear that in relation to climate, less and less people are in climate denial. More and more people understand it's necessary to do, but we are not yet there. And even this increased conscience of fragility that the COVID brought has not yet allowed to wake up some or at least many of our most powerful leaders.

Ian Bremmer:

I mean the positive piece of the report, of course, was precisely that so many countries around the world now basically agree on the facts, basically agree on, yeah, we've warmed by 1.1 degree Celsius already. These are the implications of that. Five years ago you couldn't say that. But we clearly don't have the urgency and we clearly don't have the trust.

Now I mean, given the fact that the gap between developed and developing worlds is only growing, and the mistrust is only growing, what do we do to address that issue? How do you begin to bridge that?

António Guterres:

I think we need to use all opportunities to create conditions for dialogue and for people to understand each other and to understand the position of the other. The dramatic thing when two talk to each other is that we have not two but six, what each one is, what each one thinks he or she is, and what each one thinks the other is. This is true for people. I learned it with my late wife that was a psychoanalyst. But this is also true for countries and it's true for social groups within a society.

The perception that exists today of the United States in relation to China is very different from the perceptions that Chinese have about themselves and for what China really is. And the perception that China has about United States is very different from what United States think about themselves and for what the United States are. And these six make it impossible to come to an understanding because we are talking about different perceived realities.

So the most important thing I believe I can do as Secretary General is item by item, area by area, group by group to try to make people understand that these six need to be back to two. We need to know who we are, who the others are, and understand we have different positions, but a common interest.

Ian Bremmer:

As someone who talks to all of these leaders all the time, how have your perceptions changed of the Americans in the world and of the Chinese role in the world over the last, over your first term as Secretary General?

António Guterres:

I think the two countries have evolved enormously in the sense that the United States moved from the Trump administration to the Biden administration, and that of course represents a totally different view to look into governments. And I think that there is a serious effort to make lying wrong again in the American society, which is a positive thing. But we know that these things are always fragile.

On the other hand, the truth is that China has become much more assertive about its economic weight and much more conscious about its role. And this evolution have created a basic misunderstanding about the two countries. And I've been saying since the beginning, it is clear for me that there is a clear divide in relation to human rights and the clear divide in relation to some geostrategic issues, namely the South China Sea.

It is clear to me that there is an area where there should be conversions, climate, and there are areas where there should be a serious negotiation. There are differences, but I mean, I don't want to see the world divided into two. I don't want to see a decoupling, a global decoupling, economic and technological. I think, it would be good to have one single economy with one single set of rules. But this requires a serious negotiation because obviously things have evolved. So obviously we need a redesign that requires a serious negotiation.

The problem is that we had the division exacerbated on the questions of human rights and the geostrategic questions. That was inevitable. And we also had a division on all questions related to trade and technology. And so the only thing in which there is an area of potential convergence is climate.

Ian Bremmer:

Climate.

António Guterres:

And what was demonstrated in the recent days is that this is a model that doesn't work.

Ian Bremmer:

Why do you think that happened?

António Guterres:

Because I believe if you take what Chinese have said, there was this expression that we cannot have an oasis about climate in the middle of desert about everything else. I think if there was a serious negotiation on the questions of trade and technology recognizing the differences, these would probably rebalance the relationship.

Of course, the divisions on human rights and about Taiwan, et cetera, they would remain, but at least there will be a number of areas in which there were different interests, but a capacity to negotiate. And that will, in my opinion, facilitate the capacity to work together in the areas where I believe there is a convergence, even if the departure points of the two countries are very different.

Ian Bremmer:

Now, we do know that outside of the challenges between the US and China, the Europeans have done an enormous amount in terms of rule setting on climate. And they have advanced quite significantly in the past years. The private sector, the financial sector, including a lot of works out of your office, have moved quite significantly. How much more are you feeling that non-traditional actors in this space are fundamentally making?

António Guterres:

I hope it'll become decisive. I mean, today the Glasgow Alliance on net-zero represents, if I'm correct, 87 trillion of assets of asset owners or managers that are committed to net-zero emissions of their portfolios in 2050. I mean, this is an historic moment from that point of view. I mean, it's the private sector that is leading the way, which everybody thought that the private sector would be the last one to accept all these complexities of moving into the green economy.

We see how the civil society is totally committed. We see the youth totally mobilized. So I feel governments are having more and more pressure about climate. Look at the German election that are taking place now. The issue is climate. I mean, a few years ago the issue was migration. So things are changing. And I hope this will help to wake up the leaders because the future of many political leaders in the world will soon be dependent essentially on how they deal with the climate question.

Ian Bremmer:

And you said yourself, it used to be the United States could do the driving. Now it needs other actors. Increasingly it used to be the states that could do the driving. Now increasingly, it's also the big companies that are needed as well. How can the United Nations facilitate more effective?

António Guterres:

Of course, we still need intergovernmental bodies and governments have the legitimacy to represent their countries. But the truth is that power is less and less the monopoly of governments and it's more and more distributed in society, and power in the private sector, power in the financial sector, of course, as always in the past, power in the civil society, power in movements that, I mean, sometimes we see all of a sudden coming out of nothing and through social media et cetera gain, an enormous importance in countries.

And so we need to have multilateral institutions in which cities have a word to say, and regions have a word to say, in which the private sector has a strong contribution to give, in which the civil society must be the environment in which new things are generated to force governments to move and to have a multilateralism that is inclusive, that is able to take into account all these voices, the voice of youth, and at the same time, less fragmented that is today.

Ian Bremmer:

Could you see a future where major cities, metropolitan areas, major corporations, major banks actually had envoys to the United Nations could become signatories to international treaties?

António Guterres:

I would say treaties by definition today are treaties amongst states.

Ian Bremmer:

Yes.

António Guterres:

But we can find other instruments in which I believe the contribution of the private sector, the contribution of civil society can be incorporated. I think we need to have the capacity to reimagine the way international corporation was established.

Ian Bremmer:

So a couple other questions before we close. On Afghanistan, are we heading towards civil war right now in that country?

António Guterres:

Let's hope not. But there is a lot of unpredictability. I think the international community knows more or less, and everybody is in agreement, what would be necessary. I think it'll be good that the country could stabilize and civil war could be avoided. I think it would be very important that the country would not be any more a sanctuary for terrorists operating in other areas. I think it's very important that, of course, I don't want to transform Afghanistan in Sweden, but that in Afghanistan, a number of basic rights, namely for women and girls would be respected. And we all want the government to be inclusive and to allow for the different ethnic groups to be represented. I mean, this is what we want.

And I think the international community has some leverage. First, the Taliban wants recognition. Second, there are sanctions that they want to see disappearing. And third, they need international financial support. And at the present moment, as you know, the accounts of Afghanistan are frozen by the United States. The IMF and World Bank are not providing any resource. There is a serious cash problem in the country. So I mean, there is leverage, but it would be necessary for all the elements of the international community to come together and to engage with the Taliban positively because I think we need to engage with the reality that is there. But at the same time, to provide the Taliban the idea that they can become part of a normal world if they are able to do a number of things that are the things I described.

It's not yet clear the international community will be able to do so. We have seen the Security Council resolution is a bit weakened, and it had two abstentions. So we are not in a unanimous mood.

What we decided to do as UN was to make a bet that if, first of all, humanitarian aid is necessary, people are dying, I mean, so it's an obligation. But second, if we are able to prove to the Taliban that we can in relation to humanitarian aids, support the people of Afghanistan effectively, which also they need, obviously, I think we gain leverage to be able to obtain from them conditions for us to work properly, which means impartial distribution of aid to everybody, which means women allowed to work, which means that the girls can go to school and things of this sort.

So what I decided to do, because I mean I have no army, I have no financial power. What I decided to do, I sent my under-secretary-general on humanitarian affairs that corresponds to, I would say, a ministerial level. And he was the first person at ministerial level that went to Kabul. And Qatar was instrumental in allowing that to happen. He went there a few days ago. He met with key Taliban leaders, Mr. Baradar, Mr. Haqqani, and we tried to establish a platform to see how humanitarian aid and the conditions to make it acceptable could work.

And what I think is real is that talking to all the countries, they are ready to support humanitarian aid to Afghanistan, many are not ready to do many other things.

Ian Bremmer:

Did that meeting make you feel that the Taliban is prepared to act more pragmatically in order to maintain some level-

António Guterres:

That was the message conveyed by the Taliban. But if there is something about Afghanistan that I am totally convinced is that the situation is still unpredictable.

Ian Bremmer:

When you and I talk, we always are talking about challenges on the global stage. I'm wondering what's a surprise that you feel optimistic about that isn't in the headlines right now? Can be small, can be big.

António Guterres:

Now the only thing that makes me optimistic is to see young people that are more cosmopolitan and that feel that they are citizens of the world. And I hope that this will contribute for the need to be constantly waking up political leaders not to be necessary anymore from some time onwards.

Ian Bremmer:

António Guterres, Secretary General, great to see you.

António Guterres:

It was a great pleasure to be here.

Ian Bremmer:

That's it for today's edition of the GZERO World Podcast. Like what you've heard? Come check us out at gzeromedia.com and sign up for our newsletter, Signal.

Speaker 3:

The Gzero World Podcast is brought to you by our founding sponsor First Republic. First Republic, a private bank and wealth management company, places clients' needs first by providing responsive, relevant, and customized solutions. Visit firstrepublic.com to learn more.

And GZERO World also has a message for you from our friends at Foreign Policy. COVID-19 changed life as we know it. But as the world reopens, this moment also presents an opportunity. On Global Reboot, Foreign Policy looks at old problems in new ways. From US-China relations to gender inequality and racial discrimination, each week, Ravi Agrawal speaks to policy experts and world leaders and thinks through solutions to our world's toughest challenges. Check out Global Reboot wherever you get your podcasts.

Subscribe to the GZERO World Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or your preferred podcast platform to receive new episodes as soon as they're published.

- UN Chief: Still time to avert climate “abyss” - GZERO Media ›

- GDP should reflect cost of polluting planet, says Microsoft's John ... ›

- Podcast: Elizabeth Kolbert on extreme climate solutions - GZERO ... ›

- The Graphic Truth: Where are climate-linked scorchers deadliest ... ›

- An interview with UN Secretary-General António Guterres - GZERO ... ›