Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

Hunger Pains

A collage depicting food price increases.

A perfect storm of pandemic shortages, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and extreme weather events have driven up food prices and threatened food security globally. Now, a strong El Niño event stretching into 2024 could exacerbate this food crisis, but not for everyone.

A 2023 report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization found that as many as 783 million people worldwide faced food insecurity in 2022 – 122 million more than in 2019. The pandemic brought supply chain challenges that have been slow to abate. Extreme weather and global conflict further drove up hunger by limiting access to food. The problem is acute in the developing world, but it’s hitting people hard in North America, too.

Faint hope but gathering despair

Recent weeks have brought better news about food inflation in the US and Canada, with signs that it’s beginning to cool. In June, the Biden administration’s Council of Economic Advisers pointed out that it was slowing after a long period of elevated growth, driven largely by declining egg and fruit prices. They cautioned, however, that prices would remain above pre-pandemic levels throughout 2023.

North of the border, the Royal Bank of Canada found the same: Prices rose 18% in two years, and the rate of growth is slowing though prices are unlikely to come down. A fifth of Canadians, nearly 7 million people, lived in a food-insecure household in 2022. In the US, a study by the Urban Institute found that in 2022, a quarter of Americans reported being food insecure – a whopping 83 million people.

Peter Ceretti, director of Global Macro Geo Strategy at Eurasia Group, echoes the numbers from the Biden administration and RBC. “Consumers are seeing food price inflation begin to cool in the US and Canada, which is a good thing, but I don’t think that food price levels are likely to fall economy-wide in the near future,” he says.

Experts in the United States and Canada are already warning that changing weather will continue to drive up food prices as it delays or kills crops. And that’s not all. “In addition to putting upward pressure on prices,” Ceretti notes, “climate change introduces more uncertainty into weather patterns and growing conditions, which can increase volatility in food costs, too.”

The El Niño factor

What exactly do climate change and El Niño, the warming in the Pacific that impacts weather worldwide, bring to the table? Writing in The Conversation, David Ubilava, associate professor of economics at the University of Sydney, argues that El Niño will not have a significant aggregate effect on food prices at the global level. Instead, while the aberrant weather induces some crop failures (palm oil in Indonesia and Malaysia), it could lead to better harvests for others (in the Horn of Africa). The effects, however, will not be borne equally and could produce famine and conflict.

US Special Envoy for Global Food Security Cary Fowler has highlighted Southeast Asia, Central America, and southern Africa as particularly at-risk areas from El Niño. Meanwhile, Peru’s higher-than-normal water temperatures threaten its fishing industry.

With El Niño arriving and climate change threatening food security, the US and Canada are being asked to do more to support food aid. The Biden administration has launched the Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils. With an initial pledge of $100 million, the program is currently focused on Africa and developing resilient crops in the face of climate change. Last year, Canada announced CA$250 million in food aid, blaming Russia for soaring prices, but cut foreign aid by 15% – a projected CA$1.3 billion – in its 2023 budget.

Climate change is the game changer – and it comes with conflict

Even if El Niño spares some, climate change combined with its attendant crises, such as geopolitical instability and conflict, threatens us all. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, Europe’s breadbasket, has shown what can happen when conflict converges with extreme weather events.

Long term, the effect won’t be pretty. “Global food demand will increase by more than 50% in 2050, but due to climate change, agriculture yields of major crops could decrease over that same period,” according to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken.

Global food producers are already producing relatively smaller yields than in recent decades, says Canada’s largest farmland owner Robert Andjelic. This won’t be helped by the weather this summer, with the hottest month in recorded history – July – and wildfires that ravaged Canada and the US. In recent days, sea temperatures in Florida broke records – hitting 101 degrees Fahrenheit. El Niño or no El Niño, extreme temperatures, and weather events are going to hurt crops and affect food prices and security.

Andjelic issued a stark warning that he expects high food prices to become the new normal when he spoke recently with The Toronto Star. “What I’m going to say is not going to be very well received by the consumer, because I see prices going much higher. This is not just in Canada. It is a worldwide supply and demand issue.”

Trade under pressure

Crop failures could also shape trade and international relations. Canada, for instance, relies on the US and Mexico for much of its produce imports. Last year, the USDA said the US was on track to become a net food importer. Canada became a net exporter in 2019 – but remains a top importer of US agricultural exports, while the US scoops up nearly 60% of Canadian agricultural exports.

Both countries, however, can feed themselves and have plenty of arable land to do so. Ceretti says deep integration and interdependence and (mostly) tariff-free exchange between the US and Canada means that while “there may be disruptions or trade imbalances that emerge in certain food products, generally, I think that trade relations will remain strong.”

But both Canada and the US rely on Caribbean, Central American, and South American states for certain commodities. Consumers may soon face higher prices for coffee and chocolate as futures in sugar, cocoa, and robusta coffee are through the roof, with the latter hitting an all-time high.

Ceretti warns that food security concerns can lead to potential export restrictions, “which can shock global food prices and make it difficult for net food importing countries to buy sufficient supplies at prices they can afford.”

Political risks abound, too

High food prices and insecurity also pose a political risk to incumbents. The 2024 US presidential race is taking shape, and in Canada, PM Justin Trudeau is due to face the electorate by October 2025.

The cost of food and other goods will factor into the US and Canadian elections, putting pressure on Biden and Trudeau to act. But with climate change running unchecked, persistent global geopolitical instability, and potentially greater and more unpredictable El Niño and other weather events in the future, just about every politician is going to face these pressures for the foreseeable future.

Listen: Following shortages that came out of the COVID pandemic as well as the war in Ukraine, the dual food problems of affordability and availability persist. While temporary impacts may be waning, the experts also discuss the longer-term impacts of the global food production system on the environment and what will - or won't - be sustainable going forward, including the food system's massive dependence on fossil fuels. In the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, Peter Ceretti, Director of Global Macro Geo Strategy at Eurasia Group, Harlin Singh, Global Head of Sustainable Investing, and Malcolm Spittler, Global Investment Strategist, and Senior US Economist, both at Citi Global Wealth Investments, discuss the latest causes and ripple effects of food shortages around the globe.

In Planting for Tomorrow: Weaving sustainability into the path toward food security, a report from Citi Global Wealth and Eurasia Group/GZERO Media, we take a deep dive into the challenges and the innovations in sustainable agriculture. This newsletter gives you an essential look into the future of food.

Listen:"We need to keep that investment flowing to come up with better ways to do this so that everyone is fed within the constraints of what the planet is able to bear," says Peter Ceretti, Director of Global Macro Geo Strategy at Eurasia Group.

In the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast produced in partnership between GZERO and Citi Global Wealth Investments, Ceretti is joined by Harlin Singh, Global Head of Sustainable Investing, and Malcolm Spittler, Global Investment Strategist and Senior US Economist, both at Citi Global Wealth Investments, to discuss the latest causes and ripple effects of food shortages around the globe.

Following shortages that came out of the COVID pandemic as well as the war in Ukraine, the dual food problems of affordability and availability persist. While temporary impacts may be waning, the experts also discuss the longer-term impacts of the global food production system on the environment and what will - or won't - be sustainable going forward, including the food system's massive dependence on fossil fuels.

This episode is moderated by Shari Friedman, Eurasia Group’s Managing Director of Climate and Sustainability.

Peter Ceretti

Director, Global Macro-Geostrategy, Eurasiia Group

Harlin Singh

Global Head of Sustainable Investing, Citi Global Wealth Investments

Malcolm Spittler

Global Investment Strategist and Senior US Economist, Citi Global Wealth Investments

Shari Friedman

Managing Director of Climate and Sustainability, Eurasia Group

More than a year after Russia's war in Ukraine, have we turned from not enough food to more expensive food for all? How is this having different impacts in the developed and developing world?

Who's to blame for food inflation? And can the US and Canada do something to make food more available and affordable for the rest of the world?

At a US-Canada summit, GZERO's Tony Maciulis caught up with Ertharin Cousin, who knows a thing or two about this stuff as CEO of Food Systems for the Future and former head the UN World Food Programme.

For more, sign up for GZERO North, the new weekly newsletter that gives you an insider’s guide to the world’s most important and under-covered trading relationship, US and Canada.

- Global food crisis: when food isn't merely expensive ›

- If we don't act fast to help smallholder farmers, developing world might soon run low on food ›

- Podcast: The Ukraine war is crippling the world's food supply, says food security expert Ertharin Cousin ›

- How Russia's war is starving the world: food expert Ertharin Cousin ›

A vendor arranges onions for sale at a market in Lagos, Nigeria.

Thanks to the war in Ukraine and the pandemic before it, food inflation remains sky-high throughout much of the world. With the Black Sea grain deal set to expire on March 18, we take a look at global food security in 2023 with Eurasia Group expert Peter Ceretti.

Is the food security crisis over?

Unfortunately, not yet. International prices have moderated for staple grains — like wheat, and corn — since early- to mid-2022, but they’ve stabilized at a high level.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, food prices had already been disrupted by COVID-19. The war led to a blockade of Ukraine’s ports, higher energy and shipping costs, and Western sanctions and self-sanctioning targeting Russia, all of which caused prices for wheat, corn, and other grains to spike.

As the world learned, Ukraine and Russia are major exporters of wheat, maize, barley, and sunflower seeds and oils, and prior to the war, Ukraine used to ship most of its food exports through the Black Sea. Russia and Belarus are also major fertilizer exporters, especially to the MENA region and sub-Saharan Africa.

Over time, Ukrainian producers adjusted, shipping more of their crops westward over land and by river. Then, in July 2022, Russia and Ukraine reached a deal brokered by Turkey and the UN to reopen some of Ukraine’s ports for food shipments, helping to restore Black Sea shipments to Turkey, Europe, the Levant, and North Africa, among other destinations.

This helped to relieve concerns over shortages. Coupled with the Federal Reserve’s tightening cycle, and eventually a moderation in oil and gas prices, the improved outlook brought food prices down.

“Down” is a relative term though. Using the FAO’s Food Price Index as a benchmark, food prices are about 8% lower now than they were a year ago, but they’re also about 11% higher than they were in early 2021 and around 30% higher than in early 2020.

So availability is now less of a concern, but basic foodstuffs are still very expensive.

Why are food prices still so high?

Good old supply and demand are a part of the story. The USDA forecasts that global production will fall for rice and corn this year and that consumption will outstrip production for wheat, rice, and corn. There should be enough to go around in the aggregate, but this will mean that global stocks will fall compared to last year’s levels. A tight market keeps a floor on prices.

Inputs are another factor. Oil and gas prices are still relatively high, driving up prices for fuel used for farm equipment as well as for transportation and refrigeration. Natural gas is also used as a feedstock for nitrogenous fertilizers, and even though prices have come down in recent months, this year’s harvests could be affected by under-application in 2022.

Weather is a third consideration. We’ve had an exceptionally long “triple-dip” La Niña, which can lead to extreme weather events that are also becoming more frequent due to climate change. La Niña is expected to recede, but there’s a good chance that El Niño conditions will set in by late 2023, which could bring more disruptive weather.

What consumers pay for food does not correspond one-to-one to international price developments, either. Many food products are consumed in the country where they are produced. Most countries subsidize agriculture and enact some degree of protective trade policies. In wealthy countries, a large share of food spending goes to marketing and distribution, and only a small share of food prices — around 15% in the US — are determined by the actual cost of food. Finally, other factors like exchange rates and regional discrepancies in food costs can also distort the relationship between domestic and international food prices.

In practice, this means that the pass-through from changes in international prices to domestic food costs is partial and occurs with variable lags. There’s even some recent evidence to suggest that more of price rises on international markets is passed through to consumers than price falls. So even though international food prices are falling year on year, about 90% of countries are seeing consumer price inflation on food of 5% or more. In January, the median food inflation rate was about 14%.

What is the outlook for staple foods for the rest of 2023?

At present, the outlook is mixed. Barring any major, unexpected developments, I think prices are likely to continue to fall on a year-on-year basis through mid-2023, though there are some important uncertainties. Weather and the possible onset of El Niño later in the year is one factor.

Oil and gas prices are another consideration. My colleagues think that it’s likely oil and gas prices will rise again in the second half of 2023, as China’s economy gains steam, Europe recovers, and supply-side conditions remain tight — especially given Europe’s energy decoupling from Russia. This would help to drive food and fertilizer prices upward again.

What about the Black Sea Grain Initiative?

The continuation of the grain deal is a major wildcard. Our view is that the deal will be renewed. Russia has structural incentives not to let it lapse, as it nearly did last November. Among other things, Moscow is seeking to maintain ties with developing countries, which have been hit hardest by higher food costs and are disinterested both in the war and in Western sanctions. China, for instance, has purchased over 20% of the grains and oilseeds shipped through the grain deal and has sought to interject itself into diplomatic efforts to end the war. Turkey and Iran are also major beneficiaries of the deal.

On the other hand, killing the deal would bring the Kremlin closer to crippling the Ukrainian economy. About 11% of Ukrainian GDP came from agriculture prior to the war, and Putin aims to do long-term damage to Ukraine’s economic structure.

Are there any other factors to watch?

Rice is another watchpoint. Rice prices have been decoupled from other staple grains throughout the conflict, and they fell for much of last year. But international prices are now rising by around 17% year on year, and given the number of countries in Asia that depend on rice as a staple, this should be a point of concern. Most East, South, and Southeast Asian countries have support programs in place to shield the population from major rice price movements, and much of the rice that is consumed in the region is produced domestically. But a knee-jerk restriction on exports from a major rice exporting country, like India, has the potential to spike prices internationally.

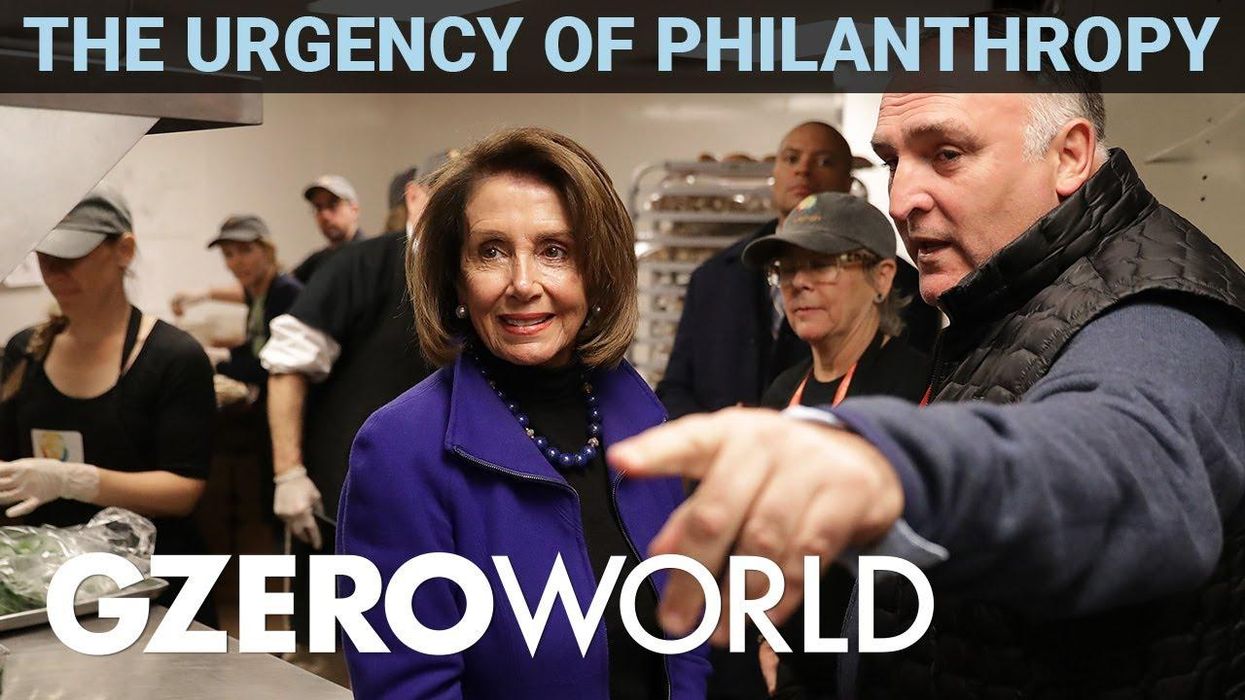

In today's world, where global development needs are high and seismic geopolitical events have turned back the clock on so much progress, UN Foundation President Elizabeth Cousens says its the perfect time for philanthropy to step up.

Indeed, there's a lot more that can be done, Cousens tells Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

And philanthropy, she explains, doesn't have to be about greenwashing or PR but rather a way of making things better in many places that have been through more than their fair share in recent years.

Cousens believes there's been a "real reckoning" among people and corporations who are "increasingly recognizing their contribution to the state of the world that is not particularly healthy." And there's the opportunity for them to do real good.

Watch the GZERO World episode: Inequality isn't inevitable - if global communities cooperate

On global issues, the international community must walk and chew gum at the same time. It needs to learn to deal with simultaneous crises that play off each other, says UN Foundation President Elizabeth Cousens.

That's why we dropped the ball on hunger.

Now the needs are huge and growing. We haven't seen a lot of images of starvation yet, but they are coming, Cousens tells Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

"We have to be able to rise to this challenge, and see it as something that's in both our interest," she says, adding that “we have done heroic things before on the humanitarian front — it's not like we're not collectively capable."

Watch the GZERO World episode: Inequality isn't inevitable - if global communities cooperate

Listen: Global inequality has reached a level we haven’t seen in our lifetimes and recent geopolitical convulsions have only made things worse. The rich have gotten richer while extreme poverty has exploded. UN Foundation President Elizabeth Cousens thinks it's the perfect time for institutions backed by the 1% to step up. She speaks with Ian Bremmer on the GZERO World podcast about the key role that innovative philanthropy could play to address problems exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, economic fallout from the COVID pandemic, and a warming planet.

Why now? The stakes are so high and the crises so urgent that Cousens sees a window of opportunity for philanthropy to take swift action instead of their traditional long-term approach. When it comes to immediate and deadly problems like famine and flooding, an influx of money could start making a huge difference very quickly.

Subscribe to the GZERO World Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or your preferred podcast platform, to receive new episodes as soon as they're published.- Is the world coming apart? Drama at Davos ›

- Global food crisis: when food isn't merely expensive ›

- In a food crisis, export controls are "worst possible" thing to do, says UN Foundation chief ›

- Podcast: The Ukraine war is crippling the world's food supply, says food security expert Ertharin Cousin ›

- Inequality isn't inevitable - if global communities cooperate - GZERO Media ›

- Philanthropy's moment to act - GZERO Media ›