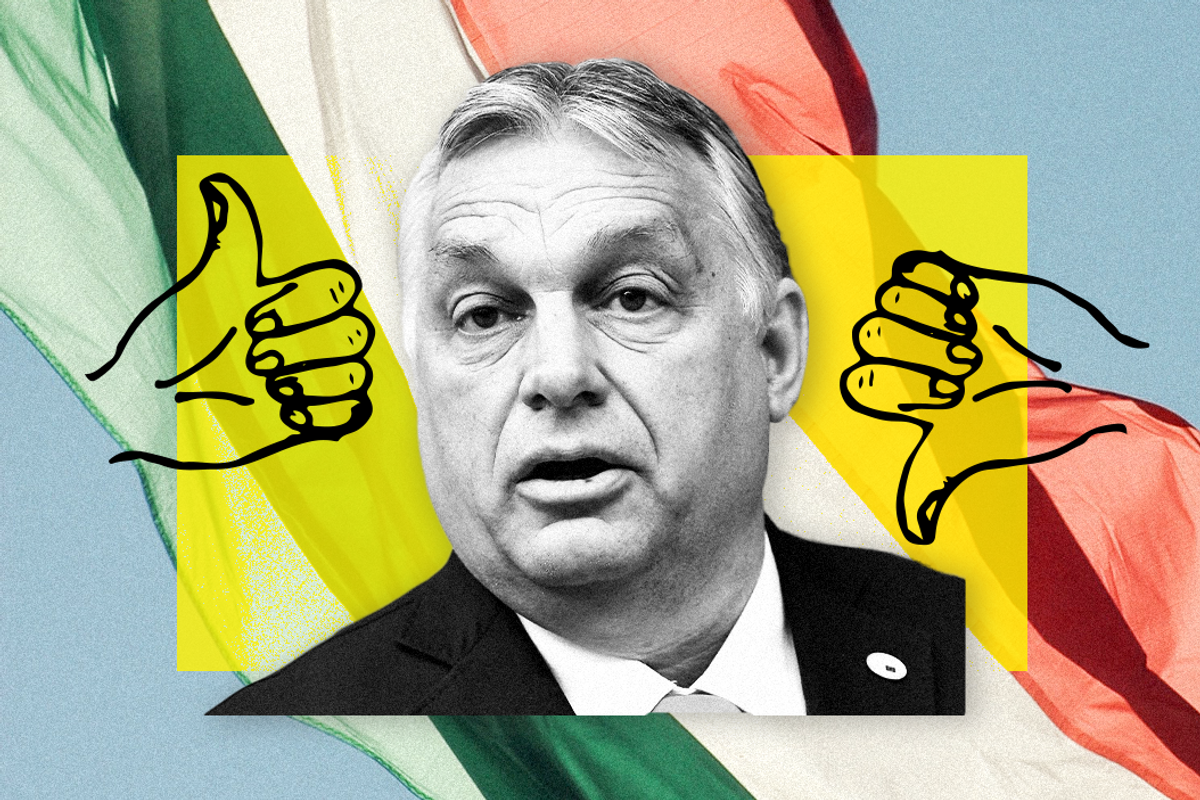

Viktor Orbán, Hungary's far-right populist prime minister, likes to shock people. It's part of his political appeal. Orbán has proudly proclaimed that he is an "illiberal" leader," creating a frenzy in Brussels because Hungary is a member of the European Union.

It's been over a decade since the 58-year old, whom some have dubbed the "Trump before Trump" became prime minister. In that time he has, critics say, hollowed out Hungary's governing institutions and eroded the state's democratic characteristics.

But now for the first time since then, Orbán faces a real challenge to his power. Six ideologically-diverse opposition parties have joined forces to unseat him. But even if the opposition bloc wins elections next spring, a hard feat given Orbán's popular appeal, what would it even mean to "liberalize" Hungary again?

Orbán: Liked but not loved. Early in his political career, Orbán learnt that popular resentment could be harnessed as a political weapon. After the collapse of Hungary's communist regime, Orbán, a student who grew up in the countryside without running water, became a founding member of Fidesz (then called "Alliance of Young Democrats"), an anti-communism youth party. Under his influence, in particular his close alliance with Hungary's influential churches, the party took on a strongly socially conservative bent as well as a resentment of so-called "urban elites."

Since then, Orbán has fashioned himself as a bulwark against a corrupt political elite detached from salt-of-the-earth Hungarians who are tired of being pushed around by liberal elites and global heavyweights. In recent years, he has appealed in particular to Hungarians' strong sense of nationalism to rally against the progressive and migrant-friendly policies of the European Union.

Still, while Orban's anti-EU, anti-immigrant sentiment has struck a chord with many Hungarians — particularly during Europe's migrant crisis in 2015 — he has not personally endeared himself to constituents like, say, Donald Trump or Israel's Bibi Netanyahu. (No one, for example, is getting Orbán's initials inked across their chest.) Analysts say that the absence of cult-like infatuation surrounding the PM could indeed bode well for those vying to unseat him.

A ragtag opposition makes common cause. Last December, opposition parties put aside their political differences and teamed up to oust Orbán. Undoubtedly, this unsettled Orbán, who had long exploited discord within the opposition to tighten his grip on power. Tellingly, the opposition bloc — which spans the political spectrum and includes the progressive Democratic Coalition and the right-wing Jobbik party — has vowed to run unity candidates in all 106 legislative races. For now, the plan is working: Fidesz and the United Opposition are neck-and-neck in the polls.

Meanwhile, Budapest's liberal mayor Gergely Karácsony — formerly a member of the Green Politics Can be Different Party who won the mayoral race in a massive upset in 2019, defeating the Fidesz-aligned incumbent — is considered the frontrunner to head the opposition after leadership primaries take place in September. Karácsony is also a former political pollster, which is sure to come in handy on the campaign trail. Still, an upset in relatively liberal Budapest is one thing — replicating that at the national level will require winning over millions of more conservative rural voters.

What's actually at stake? Well, democracy. Hungary has taken an authoritarian turn under Orbán, who has cracked down on the independent media and restructured the electoral map to benefit Fidesz (Hungarian gerrymandering, if you will). Crucially, he has also gutted the judiciary, stacking the Constitutional Court with loyalists. And in some instances, the government has simply scoffed at court rulings. (Last year, Orbán said he would ignore a court ruling ordering the government to compensate Roma families for school segregation policies.) The EU, for its part, has condemned the erosion of the rule of law in the country, though Brussels has never been able to dish out anything more punitive than a wrist slap.

More recently, Orbán, like his ideological compatriots in Poland, has taken up the third rail issue of LGBT rights, vowing to soon hold a referendum on banning LGBT content from school curriculums. (Opposition figures said the move aimed to deflect attention from recent allegations that Orbán's government spied on journalists and activists.)

Even if the opposition wins next spring, reversing Orbán's political legacies — dilution of the independent judiciary, increased corruption and cronyism — will be extremely challenging. That's because Orbán's reforms are now entrenched in many of Hungary's institutions: for example, parliament recently appointed an Orbán ally to head the Supreme Court for nine years. Additionally, overriding big legislation requires a two-thirds majority in parliament, a pipe dream for the fragmented opposition. And even if Fidesz loses, the group will still remain immensely popular for some time.

The (potential) de-Orbanization of Hungary. Winning the election next year is only half the battle for Hungary's fired-up opposition. Reversing the political legacy of an illiberal stalwart like Viktor Orbán could take many, many years.