In this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we focus on all things inflation … including:

- Ways to address it

- Those who embrace it

- Nigeria’s eye-popping food prices

- Historical recessions

- Dinosaur skeletons

Thanks for reading.

– The GZERO Daily team

What We’re Watching: Three ways to address inflation … with varying degrees of success

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiErdonomics: Growth > stability

Turkey has long had a hyperinflation problem, but that doesn’t mean that its central bank has sought to raise interest rates to bring prices down. In fact, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose unorthodox economic approach has been dubbed Erdonomics, has even sought to lower interest rates during inflationary times. Why?

Central to his approach is the belief that economic growth trumps all, including price stability. So Turkey’s central bank has been unwilling to raise interest rates to reverse hyperinflation, and Erdogan has even called himself an “enemy” of interest rates.

As the Turkish president explains it, keeping interest rates low – and static – stimulates demand, driving economic growth.

But that hasn’t panned out. Inflation in Turkey soared to a quarter-century high of 85% in October – largely due to roaring food and fuel prices. Crucially, analysts think the official number was closer to 186%, meaning prices would have almost tripled. As a result, the average Turk has far less disposable cash to inject into the economy. What’s more, Turkey has seen its currency, the lira, plummet a whopping 90% since 2008.

What do Turks think of the cost-of-living crunch? They will get to weigh in on May 14, when the country heads to the polls. Erdogan is facing a united opposition that has been pushing the message that he has wrecked the economy.

Price controls and unintended consequences

Inflation = prices going up. But what if they just … didn’t?

That’s basically the thought process behind price controls, an alternative tactic for fighting inflation where the government mandates maximum prices for goods. While this might sound good, price controls remove the magical balance of supply and demand: When something is expensive, it signals to producers that they can profit by increasing supply. But if the government artificially holds down prices, producers aren’t incentivized to meet demand, which leads to supply shortages, inefficiencies, and unintended consequences.

Most economists believe that monetary policies can tame inflation without capping prices. But with inflation now running rampant, some left-wing policymakers and economists are revisiting the idea. In 2022, US Sen. Elizabeth Warren proposed a bill to outlaw “abusive price gauging” during market shocks. Progressives argue that price caps help the poor, but there’s a catch.

The thing about price controls is that they tend to work in the beginning. In 1971, President Richard Nixon tried to nip inflation in the bud by implementing a 90-day freeze on most wages, prices, and rents. The result: Inflation fell by 50% ... at first. But as soon as the government eased restrictions, prices shot back up, requiring another round of caps that barely made a dent. The takeaway: Price controls might help in the short run, but not in the long run.

Argentina has long been addicted to using price controls for political gain. In late 2021, after an electoral loss attributed to 53% inflation, the ruling party slapped price controls on over 1,400 products. But like the last time the government did this in 2013, it’s only making inflation worse — currently over 100% year-on-year.

The historical upshot of price controls: When the precise balance of supply and demand is replaced by the blunt axe of government policy, the solution is more likely than not to be worse than the problem.

The Goldilocks approach to adjusting interest rates

Western central banks are, broadly speaking, focused on two key things: Keeping inflation down and employment up. To strike the right balance, and, like Goldilocks, ensure that the economy is neither too hot nor too cold, many central banks adjust interest rates to prevent the economy from overheating.

Given the inflationary pressures of the past year – as a result of the war in Ukraine, supply chain kinks, and pandemic stimulus – the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England, Bank of Canada, and others, have aggressively raised interest rates to increase the cost of credit within their respective economies.

While interest-rate policy aims to keep consumer prices steady (global food prices, in particular, have soared), central banks’ policies also influence – and are influenced by – financial behaviors.

For example, market turmoil in the US in recent times has tampered with investors’ appetite for risk. This has partly contributed to mass layoffs in the tech sector, something the Fed is watching closely as it adapts its interest-rate policy.

But not all wealthy countries are adopting this approach. For instance, the Bank of Japan, which has long focused on keeping interest rates low to stimulate growth, has left interest rates at - 0.1%, leading to stubbornly high prices for consumers.

__________________________________

Not everyone hates inflation – just ask the dinosaur skeletons

Rising prices are a headache for most people, but not everyone is unhappy. People who have low fixed-rate mortgages or other fixed-cost debts, for example, actually get a break from inflation, because it has the effect of reducing the burden of repaying or servicing what they’ve borrowed. Paying what they owe costs less because the currency has lost value compared to when they took out the mortgage.

Meanwhile, there are folks who hold assets that tend to rise in value when inflation goes up, such as stocks in energy or food production companies. Another is gold, which generally rises in value during bouts of inflation because it’s seen as a more stable store of value — after all, it’s been used as money for 2,500 years.

But the most colorful beneficiaries of inflation may be hoarders or other collectors of items like Rolex watches, fine art, classic cars, designer handbags, sports memorabilia, fine wines, and even dinosaur skeletons!

As inflation drives down the value of money, people invest in items like these, which are seen to hold value more predictably than cash. Not everyone has access to a fine wine cellar or a classic car garage, but surely you’ve got an unexpected inflation hedge lurking in some old shoebox somewhere, don’t you?

Tell us what you collect/hoard for rainy days here.

CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Carlos Santamaria

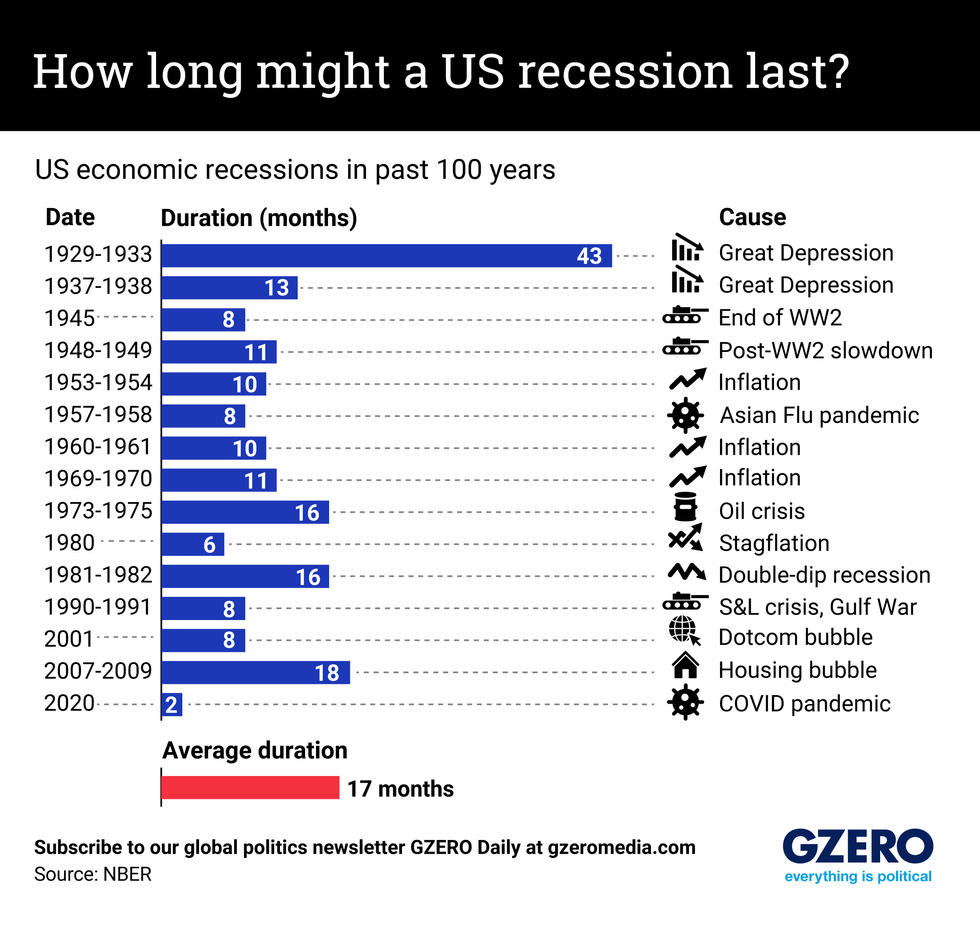

Carlos SantamariaFor months, we've been debating the odds of a looming inflation-fueled US recession. It hasn't happened yet — in no small part due to a tight jobs market. (For more on who makes the recession call, read our primer here.)

But the fact that it hasn't happened yet doesn't mean recession fears are over. In fact, economists believe it'll start as soon as cash-strapped businesses — faced with high interest rates to fight inflation — begin giving workers pink slips across the board. Still, it's more likely than not that when it comes, the recession will be not only mild (not triggering mass unemployment) but also historically short.

We take a look at the duration and cause of US recessions over the past century.

Staving off default: How unsustainable debt is threatening human progress

At last week’s World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings, GZERO Media spoke with Navid Hanif, assistant secretary-general for economic development at the UN, about the fact that three-fifths of the lowest-income countries in the world are debt distressed and in danger of default.

Hanif explains how a financial divide will eventually become a development divide, which is not good for the world. While stressing the urgency of the growing debt problem, Hanif also expresses optimism about the potential for post-pandemic progress, citing the growth of internet access and a renewed commitment to climate goals.

Hard Numbers: World inflation champs, hyperinflation history, device deflation, how much do you spend on food?

Alex Kliment

Alex Kliment538: What country currently has the highest annual inflation rate in the world? Crisis-wracked Lebanon (190%) is up there, and so too are the perpetually mismanaged economies of Argentina (103%) and Zimbabwe (92%). But at the moment, independent economists say Venezuela’s annualized price growth is running at a dizzying 538%. A combination of overspending and a plummeting currency is to blame.

143: You’ve probably heard about the quadrillion percent inflation that took hold in post-World War II Hungary, an episode generally regarded as the worst example of hyperinflation in modern history. But the one that started it all was in France more than 150 years earlier, when in the months after the French Revolution, inflation hit 143%. Let them eat cake, indeed.

24: Is anything getting cheaper these days? Yes! It’s in your hand/pocket/purse! According to the latest US Consumer Price Index report, which tracked prices through February, the item that has shown the biggest price drop is … smartphones, which cost 24% less than a year ago.

59: How much does food price inflation hurt? In Nigeria, households spend an average of 59% of their income just on eating. The figure for most emerging and developing economies is above 25%, while among the wealthiest G7 economies, it’s closer to 15% or less. In the US, an average household spends just below 7% of its income on food.Podcast: Recession or not?

GZERO Staff

GZERO StaffIn the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast produced in partnership between GZERO Media and Citi Global Wealth Investments, Eurasia Group’s Rob Kahn has a frank discussion with Charlie Reinhard, head of Citi’s Investment Strategy for North America, about the state of the economy and unemployment. They dive into the sticky rates of inflation, what the Federal Reserve is going to do about it, and what kind of recession – if any – investors should expect.

This special edition of GZERO Daily was written by Riley Callanan, Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, and Carlos Santamaria. It was edited by Tracy Moran. Graphic by Luisa Vieira, art by Annie Gugliotta.