Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

In this special edition of GZERO Daily, in partnership with Citi Global Wealth Investments, we focus on the uncertainty stalking the global economy.

Today we’ve got:

- Three geopolitics stories that could boost/burn the global economic recovery

- A white-knuckle ride to renewing the Ukraine grain deal

- Growing tech layoffs (even before Friday’s SVB blowup)

- An unexpected link between Xi Jinping and Kurt Cobain?

Thanks for reading.

The GZERO Daily team

What geopolitics stories could still blow up the global economy?

Investors hate uncertainty. For now, most of them are trying to understand how central bankers, particularly at the US Federal Reserve, will calibrate changes in interest rates to slow inflation while avoiding recession.

But there are also three big geopolitical stories that will generate plenty more questions throughout 2023.

Russia’s war

After more than a year of war following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, two realities have emerged. Russia’s military isn’t strong enough to conquer Ukraine, but it is probably strong enough to prevent a complete Ukrainian victory. The war has now settled into a stalemate that continues to put upward pressure on energy prices and threaten further surges in food prices. (The current deal to allow grain exports through the Black Sea expires on March 18.)

To some extent, the consensus expectation for a war that lasts beyond 2023 will allow producers and companies to adjust their supply chains to new realities, to make alternative arrangements for diminished supplies of oil, gas, grain, and other commodities, and to find new trade partners.

But wars create surprises, and Russia’s inability to win the war leaves its leaders to think up creative new ways to punish Ukraine and its backers, with attacks in cyberspace, on pipelines, or on fiber optic cables, for example, adding wildcards to a deck already stacked against a predictable economic recovery from COVID.

China’s rebound?

In a time of war and global economic uncertainty, China poses a long list of questions. After all its extended COVID lockdowns, can Chinese leaders jumpstart China’s own economic growth to inject new fuel into global commerce? The relatively modest growth target the Chinese leadership recently announced generates optimism that Beijing has a realistic understanding of the risks in pushing too hard too quickly on state spending and loose lending. Has China finally cleared its COVID hurdles? There’s a lot of optimism on that front. Will US-China relations continue to deteriorate? If Washington decides that Xi Jinping’s government is trying to boost Russia’s odds of winning the war, that’s a safe bet.

Iran in flux

Two weeks ago, a senior US Defense Department official issued a startling warning. “Back in 2018,” he said, “when the [Trump] administration decided to leave the JCPOA, it would have taken Iran about 12 months to produce one bomb's worth of fissile material. Now it would take about 12 days.” That followed news in February that the International Atomic Energy Agency charged with monitoring Iranian nuclear facilities had reported finding small quantities of uranium enriched at 84%. (Enrichment at 90% can produce a nuclear weapon.)

This is a country preparing for its first transition of supreme leadership in more than 30 years, given Ali Khamenei’s advancing age and declining health. (He’ll be 84 next month.) It has faced widespread protests. The unrest seems to have died down for the moment, but given how abruptly the upheaval began, some new and equally unexpected trigger could start the cycle of demonstrations all over again. And Iran’s willingness to provide Russia with drones for use against Ukraine has newly antagonized Europeans as well as Americans.

There are fears in Israel that only an attack on Iran can prevent the development of a nuclear weapon. What’s more, many say that the recent restoration of ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, is yet another sign of the deepening rift between Washington and Riyadh. Taken together, this all suggests there is constant wrangling in the heart of the world's main oil-producing region, where the US holds limited leverage.

In all these cases – Russia’s war, China’s rebound, and Iran’s flux – we have risks that are reasonably well understood. None is guaranteed to create a new and unforeseen crisis, but all of them bear careful watch through 2023 and beyond.

What We’re Watching: Grain deal deadline, tech layoffs, interest rate ripples

Gabrielle Debinski

Gabrielle DebinskiWill the Black Sea grain deal be renewed?

Amid growing concern that Russia may refuse to renew a deal to allow food and fertilizer shipments to travel through a safe passage in the Black Sea, UN Secretary-General António Guterres this week visited Kyiv, where he called for the renewal of the agreement, which is set to lapse on March 18. Quick recap: The grain deal, negotiated by Turkey, the UN, Russia, and Ukraine, was implemented in the summer of 2022 in a bid to free up 20 million tons of grain stuck at Ukrainian ports due to Russia’s blockade. You’ll likely remember that the two states are both huge exporters of wheat, while Russia is also the global fertilizer king. Indeed, the deal has helped alleviate a global food crisis that was hitting import-reliant Africa particularly hard, and driving up global food prices. Kyiv, for its part, says that if the deal is expanded to additional ports it could export at least some of the 30 million tons of grain that remain stuck. The Kremlin hasn’t said what its plans are but this week accused the West of “shamelessly burying" the Black Sea deal in what could be used as a pretext for its refusal to play ball.

For more on what Guterres has to say about the ongoing war in Ukraine and its human toll, check out his interview with Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

What should we make of the great tech implosion?

We’ve heard a lot about a downturn in the tech sector in recent months after giants including Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Salesforce, Alphabet, and Spotify laid off large chunks of their workforces. All in all, an estimated 200,000 US tech workers have been shown the door since the start of 2022 – more than the equivalent of the entire Apple workforce. At the same time, however, unemployment in the US remains at record lows, with the US adding more than 311,000 new jobs in February alone, yet another sign of the labor market's resilience. So what does – and doesn’t – the great tech debacle tell us about the current state of the global economy? First, COVID was a boon for the tech sector. As the world shut down, tech companies made the most of increased demand for work/play/eat-from-home services and embarked on massive hiring sprees. Alphabet, for example, increased its workforce by 16% between 2020-2021. But as soon as things reopened, it became clear that consumers wanted to go back to exercising in sweaty gyms and dining at overpriced ramen bars. Demand plummeted. What’s more, rising interest rates – an effort to tackle runaway inflation – and a dizzying stock market are making it harder for tech companies to raise capital and putting downward pressure on stock prices, leading to massive cost-cutting measures. Crucially, analysts warn that things will get worse before they get better.

A mountain of interest rate-driven debt

In the same way that inflation is a global problem, the fix has worldwide ripple effects. Indeed, rising interest rates to tame inflation are making it more expensive to borrow money — as well as pay it back. Last year, a group of 58 developed and emerging economies accounting for over 90% of global GDP surveyed by The Economist were on the hook for a whopping $13 trillion just in interest payments on their debt, up an astounding 25% from 2021. And this is on top of all the additional money that many countries borrowed to spend on stimulus programs during the pandemic. Everyone now owes a lot more than they signed up for at the micro and macro levels: Mortgage rates in the US have skyrocketed, corporate debt has ballooned in Hungary, and highly indebted countries like Ghana are now in even bigger trouble. So long as inflation forces central banks to keep interest rates high, access to capital will be tight for everyone: people looking to finance homes and cars, countries seeking relief from their massive debt burdens, and companies looking to raise money. And as the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank on Friday showed, this kind of risk aversion on the part of investors can — when the stars misalign — threaten to unleash broader financial chaos.CIO Strategy Webcast Series

Citi Global Wealth Investments

Citi Global Wealth InvestmentsJoin us each week on Thursday at 11:30am EST for a conversation with senior investment professionals and external thought leaders on timely market events and ask your most pressing questions.

The Graphic Truth

Gabrielle Debinski

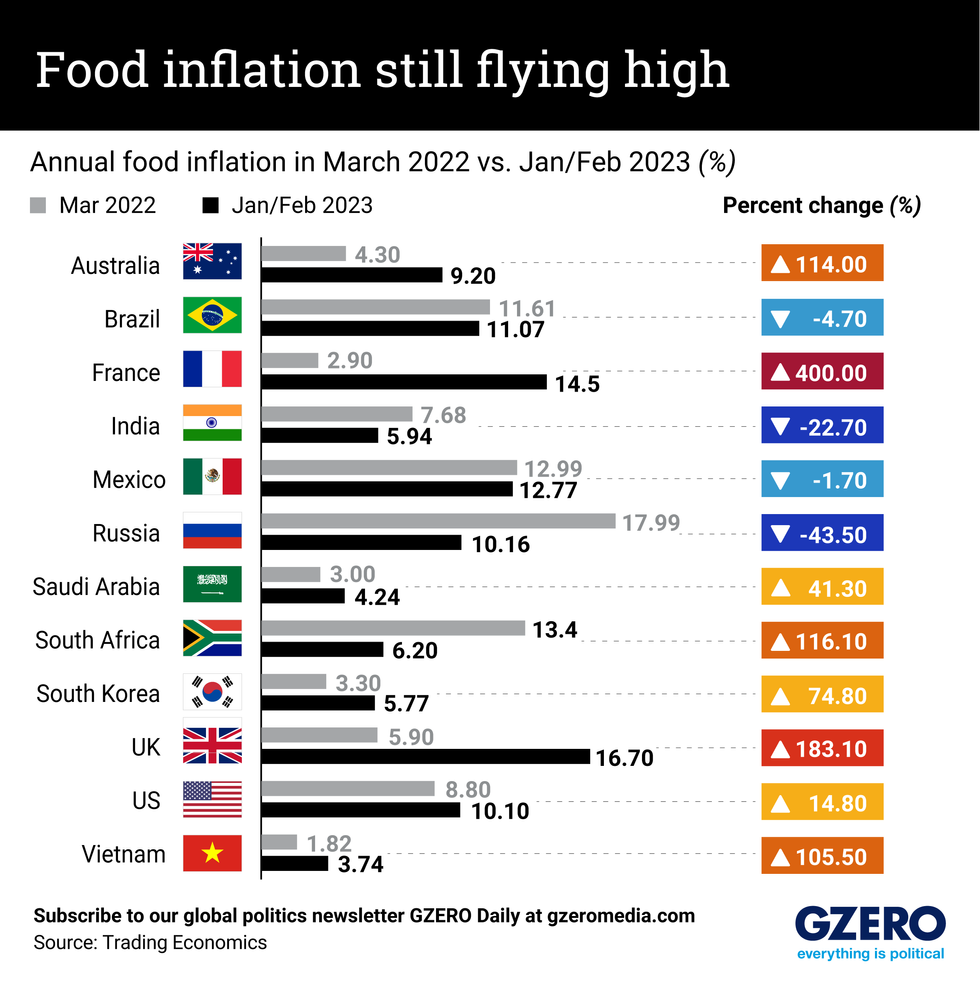

Gabrielle DebinskiAs the war in Ukraine lingers and pandemic aftershocks continue to pound the global economy, food inflation remains sky-high throughout much of the world. Consider that over the past year alone, egg prices in the US rose by a whopping 60% on average. While prices of some food staples have dropped in recent months, partly due to the Black Sea grain deal, stubborn inflation driving up transport and labor costs means that consumers aren’t feeling prices ease at the supermarket. We take a look at food inflation in select countries now compared to a year ago, exactly one month after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Hard Numbers: Beijing underpromises, Russia slips sanctions, sunlight helps to grow US jobs, oil prices in perspective

Alex Kliment

Alex Kliment32: Beijing’s new 2023 GDP growth target of “around 5%” is the country’s lowest in 32 years. The last time the Chinese Communist Party hedged this much, the Soviet Union was still around and a little-known band from Seattle had just released a record called “Nevermind.”

2.2: Despite the most comprehensive Western sanctions ever placed on its economy, Russia’s GDP shrunk just 2.2% last year, defying hopes and predictions of a much larger collapse. Why? Europe and the US were reluctant to sanction Russian energy exports too harshly, and Asian buyers were more than happy to buy up what the West wouldn’t.

126,000: Nearly a quarter of new jobs added by the US in January were a direct result of … the weather. An analysis by Morgan Stanley found that sunny skies heated up hiring in the world’s largest economy, creating an additional 126,000 jobs in the first month of the year.

40: Although oil prices have started to creep up again as China’s economy gets back to business, crude is still 40% cheaper than it was a year ago, right after Russia invaded Ukraine. Still, with China predicted to import record amounts of oil in the coming months, prices could rise more later this year.Podcast: Should I STILL be worried?

“The equivalent of what we spent in World War II was spent in the course of a year and a half to support the US economy, and that had global impacts,” says David Bailin, chief investment officer and global head of investments at Citi Global Wealth. “All of that was rolled out with incredible speed and effectiveness. And the hangover effects from that … are very, very significant,” Bailin explains on the latest episode of Living Beyond Borders, a podcast from Citi Global Wealth Investments and GZERO Media.

Bailin and Eurasia Group President Ian Bremmer, together with moderator Shari Friedman, discuss the state and future of the global economy amid the war in Ukraine. While 2023 will see slow growth, Bailin says, this resetting period will lead to significant opportunities for global growth in 2024 and beyond.

Want to know how worried you should be about the state of the economy? Tune in here.This edition of GZERO Daily was written by Gabrielle Debinski, Alex Kliment, Carlos Santamaria, and Willis Sparks. Graphic by Luisa Vieira, art by Paige Fusco. It was edited by Tracy Moran.