For many, Paul Rusesabagina became a household name after the release of the 2004 tear-jerker film Hotel Rwanda, which was set during the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

Rusesabagina, who used his influence as a hotel manager to save the lives of more than 1,000 Rwandans, has again made headlines in recent weeks after he was reportedly duped into boarding a flight to Kigali, Rwanda's capital, where he was promptly arrested on terrorism, arson, kidnapping and murder charges. Rusesabagina's supporters say he is innocent and that the move is retaliation against the former "hero" for his public criticism of President Paul Kagame, who has ruled the country with a strong hand since ending the civil war in the mid 1990s.

Indeed, this case reflects the full scope of complexities underpinning contemporary Rwandan politics and society.

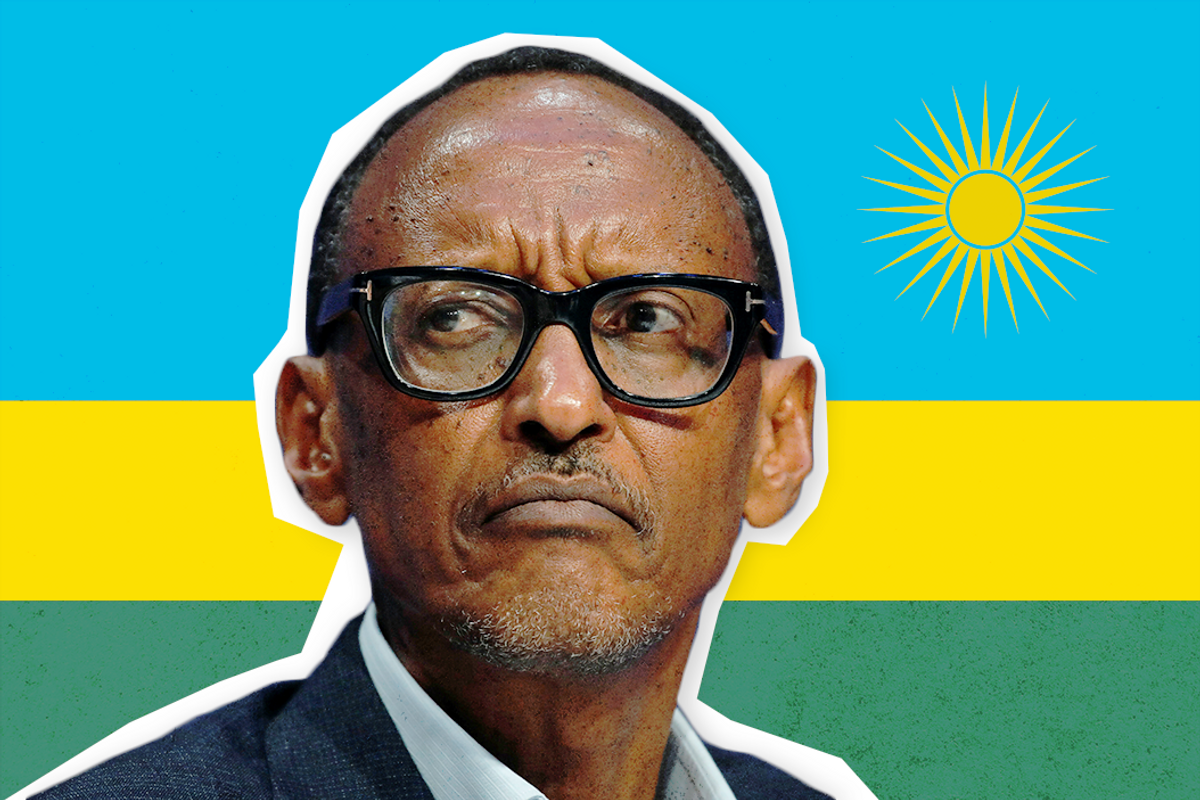

Paul Kagame: A "benevolent dictator"

Much of Kagame's worldview was formed during his formative years growing up in a Ugandan refugee camp. An ethnic Tutsi, Kagame was one of hundreds of thousands who fled during the country's decades-long civil war to escape violent attacks by the Hutu-led government.

In the waning days of the Rwandan genocide — during which Tutsis were systematically raped, tortured and murdered by their Hutu neighbors, and some 1 million Rwandans were killed — Paul Kagame commanded the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RFP), a Tutsi militia that eventually ended the Hutus' murderous campaign, emerging as the most powerful political force in post-conflict Rwanda. Kagame became president in 2000.

Since then, Kagame has been credited with overseeing a period of stability and economic prosperity after one of the world's bloodiest conflicts, but critics accuse him of widespread human rights abuses.

Internal perceptions

While many Rwandans revere Kagame for his role in ending the conflict and then putting Rwanda on the map as one of the fastest-growing economies in Africa, and one of the best places to do business in the world (in the World Bank's 2019 "Doing Business" report it ranked 29th out of 190 countries), he is also widely viewed as a strongman known for suppressing dissenting views and creating an atmosphere of growing mistrust and fear.

Indeed, politically motivated killings and enforced disappearances of high-profile political opponents in the years since Kagame took power are well documented, while human rights groups have long denounced arbitrary arrests and torture of Rwandans who dare to criticize the government.

Many Rwandans also lament the concentration of power amongst a small group of political elite who are loyal to the president. Kagame's reelection in 2017 — when he claimed to have reaped a fanciful 99 percent of the vote — was seen by many as a sham, reflective of the oppressive political environment the RFP has cultivated. Importantly, this contested election came just two years after Kagame held a referendum overriding term limits that would allow him to stay at the helm until 2034. (Vladimir Putin seemed to find this move inspiring, following suit this year.)

External perceptions

The international development community, and much of the West, have lauded Kagame for steering the country through a period of profound economic growth that's lifted at least 1 million people out of poverty. Meanwhile, Kagame's focus on expanding female representation in politics — over 60 percent of the country's lawmakers are women — has also endeared him to leaders in Europe and the US. (When US President Donald Trump met with his Rwandan counterpart in 2018, he praised Kagame's "absolutely terrific" leadership and said: "It's a great honor to have you as a friend." )

Additionally, the Kagame government's focus on promotion of new technologies and environmental policy (in 2019, Rwanda became the first African country to introduce a complete ban on all single-use plastics) has led to strong partnerships with economic heavyweights like Germany. The two countries recently created a joint pilot project to introduce electric cars to Rwanda, with plans to expand the electronic automotive industry throughout the region.

To be sure, while some Western leaders have condemned Kagame for his human rights record in the past — with Washington going so far as to cut military aid to Rwanda in 2012, citing the government's support for violent militias in the Democratic Republic of the Congo — most have been willing to look the other way because of the country's economic potential. (In the late1990s, leaders including US President Bill Clinton and the UK's Tony Blair repeatedly praised Kagame's leadership as visionary.)

A complex legacy

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian writer, philosopher and dissident, once said: "The battle between good and evil runs through the heart of every man." While Paul Kagame has pioneered reforms that have helped stabilize a war-torn country, many believe that his oppressive tactics have led to continued pain and suffering, making it hard for Rwanda's post-genocide society to fully heal.