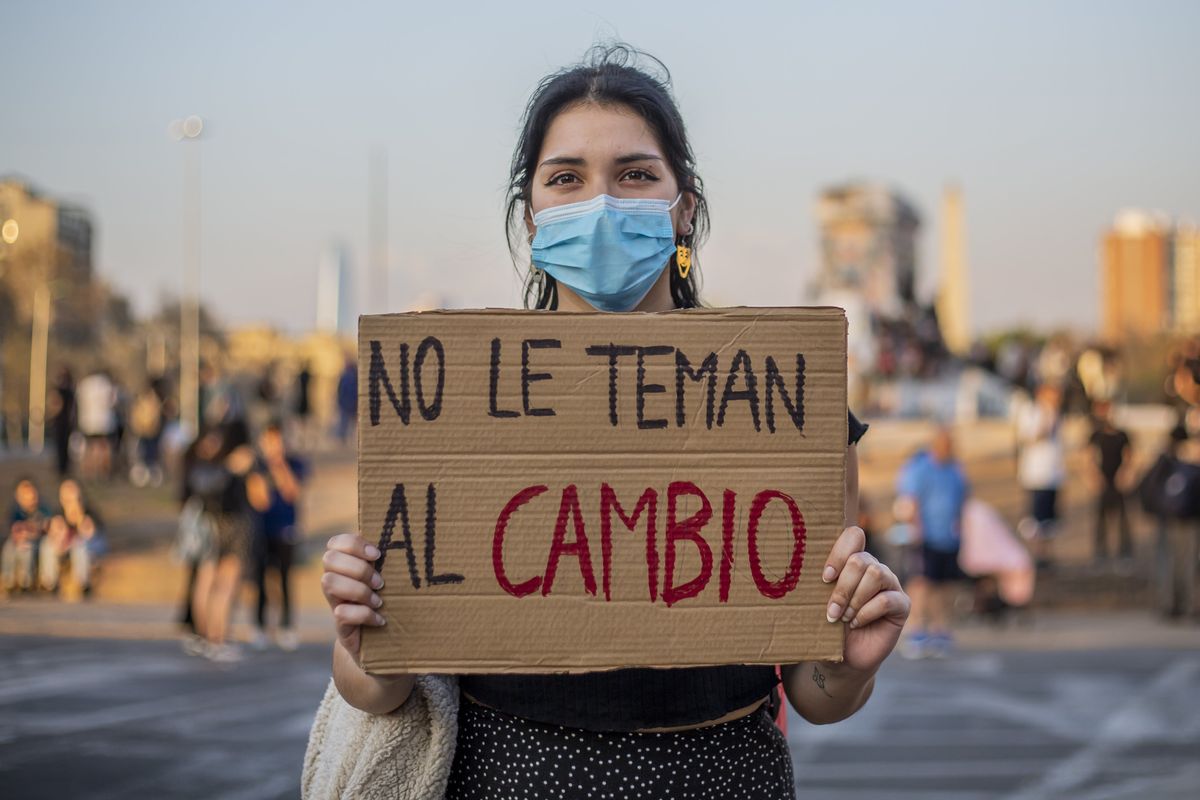

Chileans will try again this year to agree on a new constitution to replace the one drafted during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. A substantial share of the population has long wanted to jettison the Pinochet-era charter – though it has undergone significant changes over the years – and the issue became a rallying cry for the massive demonstrations that rocked the country in 2019. Yet the first attempt to do so failed when voters decisively rejected in last September’s referendum a new draft that was seen by many as moving the country too far to the left.

As the Congress-appointed expert committee prepares to start work on a new version on March 6, we asked Eurasia Group expert Luciano Sigalov what to expect from Chile’s second attempt to rewrite its constitution.

What are the next steps in the process?

The 24-member expert committee is tasked with producing a preliminary draft of a new constitution by June 6. The body comprises respected academics, former officials, and advisers to political parties; there are roughly an equal number of figures chosen by center-left and center-right parties. Separately, elections will be held for a new constitutional council on May 7, with compulsory voting. The council will start its work on a final draft of the new charter on June 7, using the preliminary version prepared by the expert committee. Supervising the whole process is a 14-member technical committee composed of legal specialists chosen by congress. It is charged with preserving core aspects of the country’s democratic system including a bicameral legislature and central bank independence. The process is scheduled to produce a new charter by Nov. 7. A ratification plebiscite, also featuring compulsory voting, will be held on Dec. 17.

What lessons were learned from the failure of the last one?

Quite a few, as is evident in the changes made to the constitutional process. The expert and technical committees represent new guardrails put in place to produce a more consensus-driven and rigorous document. Parts of the new constitution presented to voters in last September’s referendum seemed hastily cobbled together, as underscored by a commitment by its drafters to continue tweaking it had it won approval. In addition, articles in the new charter will require the approval of a three-fifths majority of the constitutional council, rather than the two-thirds previously. And limits will be placed on the participation of independents, who advanced radical proposals the first time around. Lastly, the drafting period this time will be shorter to try to prevent voter fatigue with the process.

Why is a new constitution so important for Chile?

Replacing the Pinochet-era constitution would be an important milestone for Chilean democracy and a big step forward in the political transition sparked by the 2019 protests. The country-wide, months-long demonstrations developed into the country’s most acute social and political crisis in years. Even though a new charter would not meet long-held demands to enhance the social safety net and provision of public services overnight, it would provide a more favorable framework to advance progressive reforms.

And what does it mean for President Gabriel Boric’s administration?

On the one hand, a new legal framework should make it easier for Boric to make his promised changes to healthcare and pension systems, which would expand the role of the state in providing these essential public services. On the other hand, it would represent an important symbolic victory for Boric, who has long been a leading advocate of the campaign to replace the Pinochet-era document. Last September’s rejection of the proposed rewrite was a damaging blow for his young administration (Boric took office last March).

So, what do you think – is the new charter likely to win approval?

A constitution that is more moderate and consensus-driven will certainly have better chances of approval. However, approval is far from guaranteed and will depend on its final shape and public sentiment as the 17 December plebiscite approaches. Chileans have shown they don’t like radical change, and growing discontent with the political class could sour people on the constitutional process. Although Chileans have long demanded a new charter, they seem to have grown tired of an effort that has lasted for more than three years.

What would be the consequences of another failed process?

A second failed attempt to rewrite the constitution during his administration would be another damaging blow for Boric. The political class would likely give up on trying to rewrite the constitution, at least for the foreseeable future, and the issue would become less of a priority for voters. That said, if the rejection is coupled with failed efforts to reform the pension system, a new round of protests could emerge.