Quick Take

All eyes on Russia ahead of Putin-Xi meeting

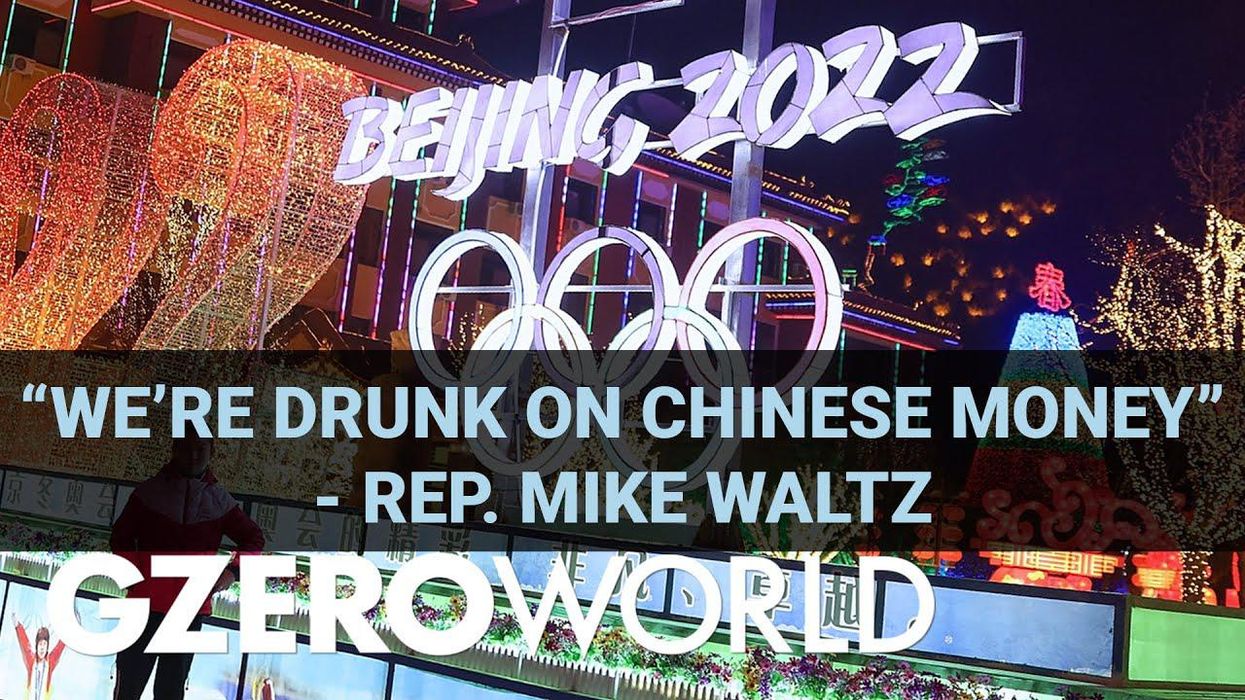

Ian Bremmer's Quick Take: If the Russians wanted to engage in a full-scale invasion, they're not quite there yet, but they certainly will be by the time the Olympics are over. That's relevant because there is this Olympics moratorium on fighting, which the Chinese actually not only co-sponsored, but actually drafted along with the United Nations leadership. And to the extent that President Putin cares at all about his relationship with China, and Beijing hosting the Olympics and Putin, traveling right over ther - it is very, very, very hard to imagine that the Russians would engage in any direct military activities in Ukraine before the Olympics are over. And certainly not while Putin is over there in Beijing for the opening ceremony.

Jan 31, 2022