Graphic Truth

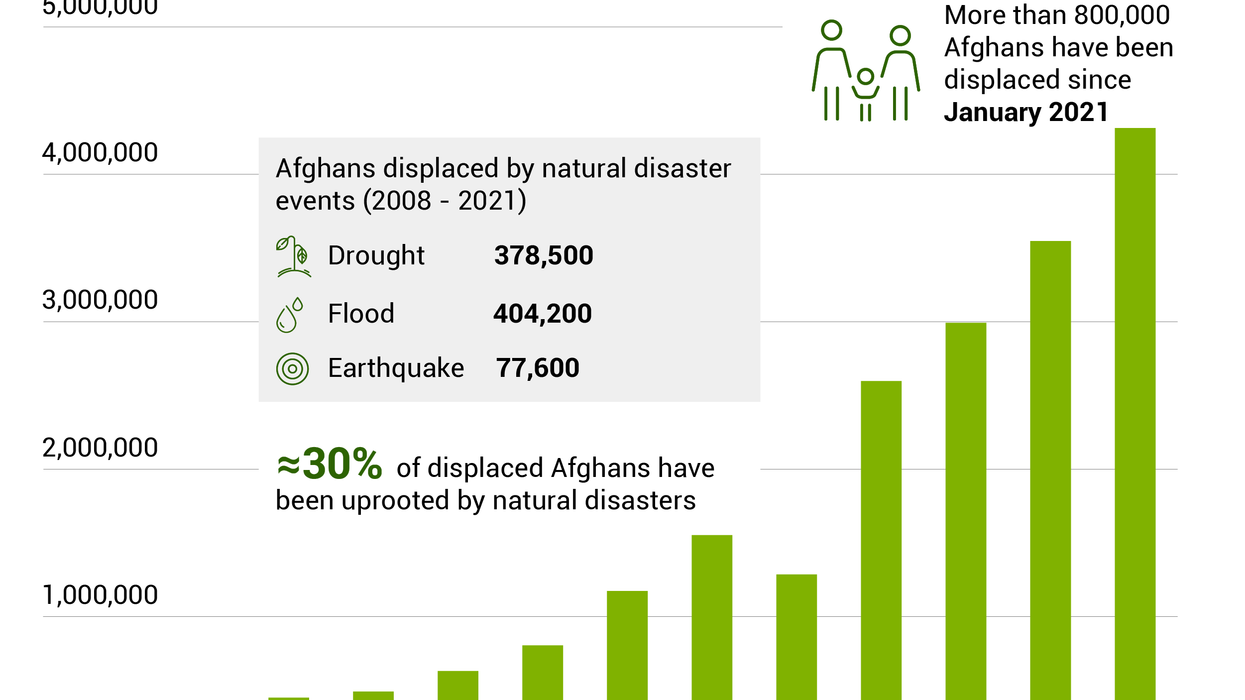

The Graphic Truth: Displaced inside Afghanistan

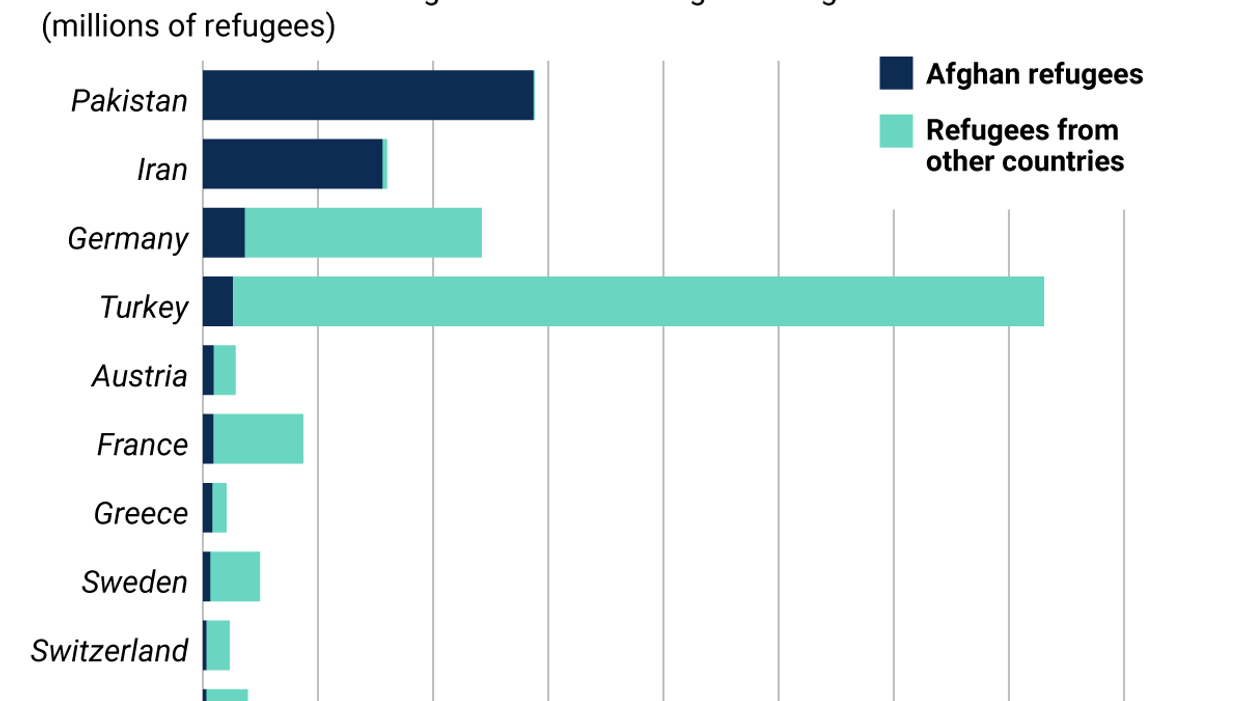

Afghanistan has been mired in war since the Soviet Union invaded the country in the late 1970s. In the post-Soviet era, the vying for influence between different clans and terror groups caused mass migration throughout the landlocked country. This trend continued under the Taliban’s oppressive rule, and the subsequent US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, which saw millions of Afghans caught in the crossfire of war. But it’s not just conflict that has led to the internal displacement of Afghans. In recent decades, natural disasters – many linked to climate change – have pummeled the country, causing hundreds of thousands to flee. We look at the numbers of internally displaced Afghans since 2008.

Aug 23, 2022