Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

Condoleezza Rice

Pioneering Black American leaders in US foreign policy

Who exactly are the people representing America to the world? Chances are they’re “pale, male, and Yale”, as the saying goes. Even in 2024, the US Foreign Service – especially in senior positions – doesn’t look like the rest of America. African Americans, people of color, and women continue to encounter barriers to influential roles.

However, some Black diplomats — like UN Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield — have broken this racial ceiling and helped reimagine what an American envoy can be. Her predecessors, through the sweep of US history, encountered discrimination and racism both domestically and abroad and left an indelible mark on US foreign policy. To mark the end of Black History Month, GZERO highlights the stories of a select few:

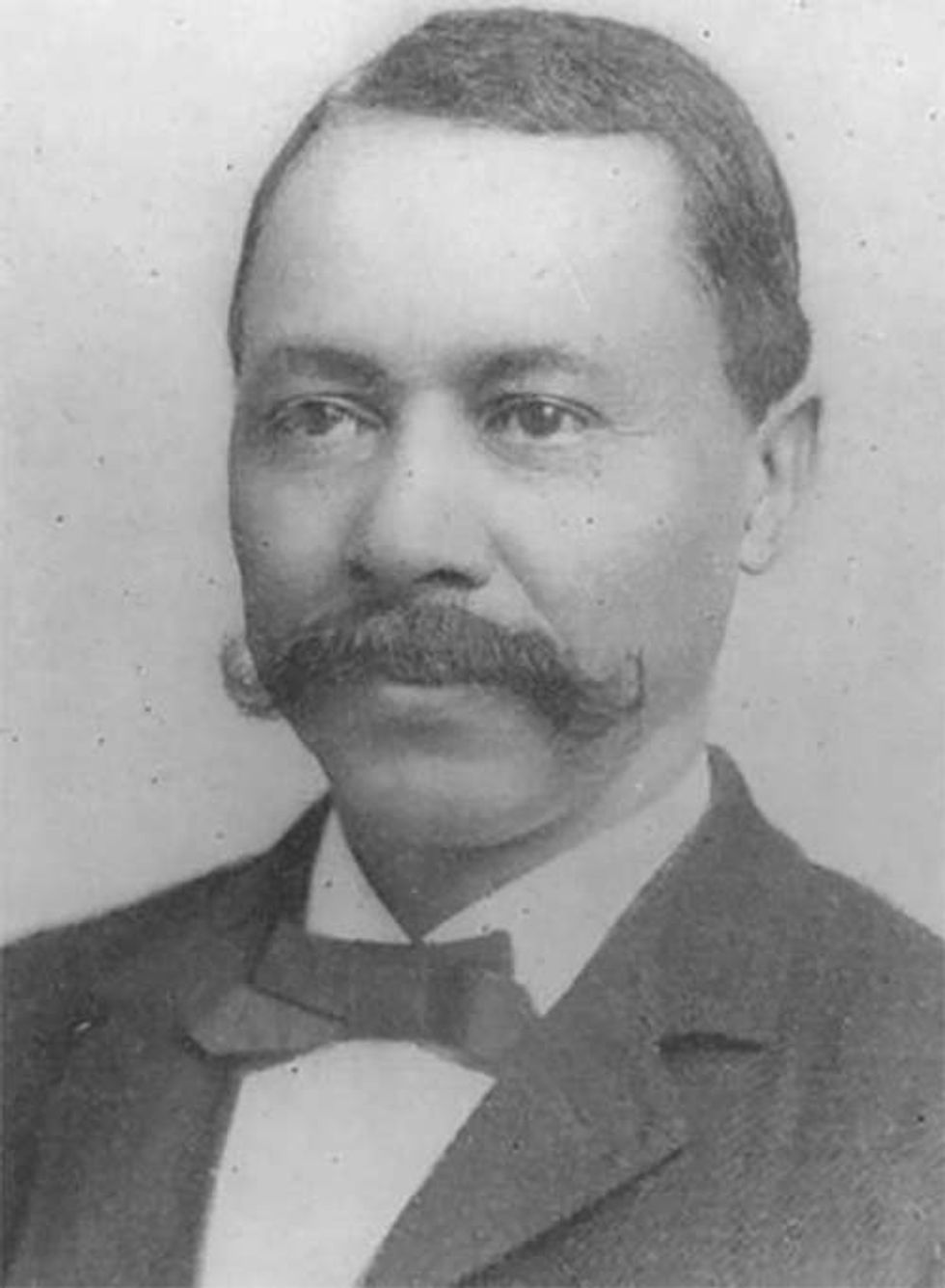

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Fair Use/National Museum of American Diplomacy

Born into a free Black family in Connecticut in 1833, Bassett broke racial barriers from the very onset of his career. He was the first Black student admitted to the Connecticut Normal School and taught at the pioneering Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia in the years before the Civil War.

His impassioned polemics for abolition and equal rights during the war thrust him into the political spotlight. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him minister to Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 1869, Basset became the first African American to serve as a diplomat anywhere in the world. Upon his return to the United States, he served as American Consul General for Haiti in New York City.

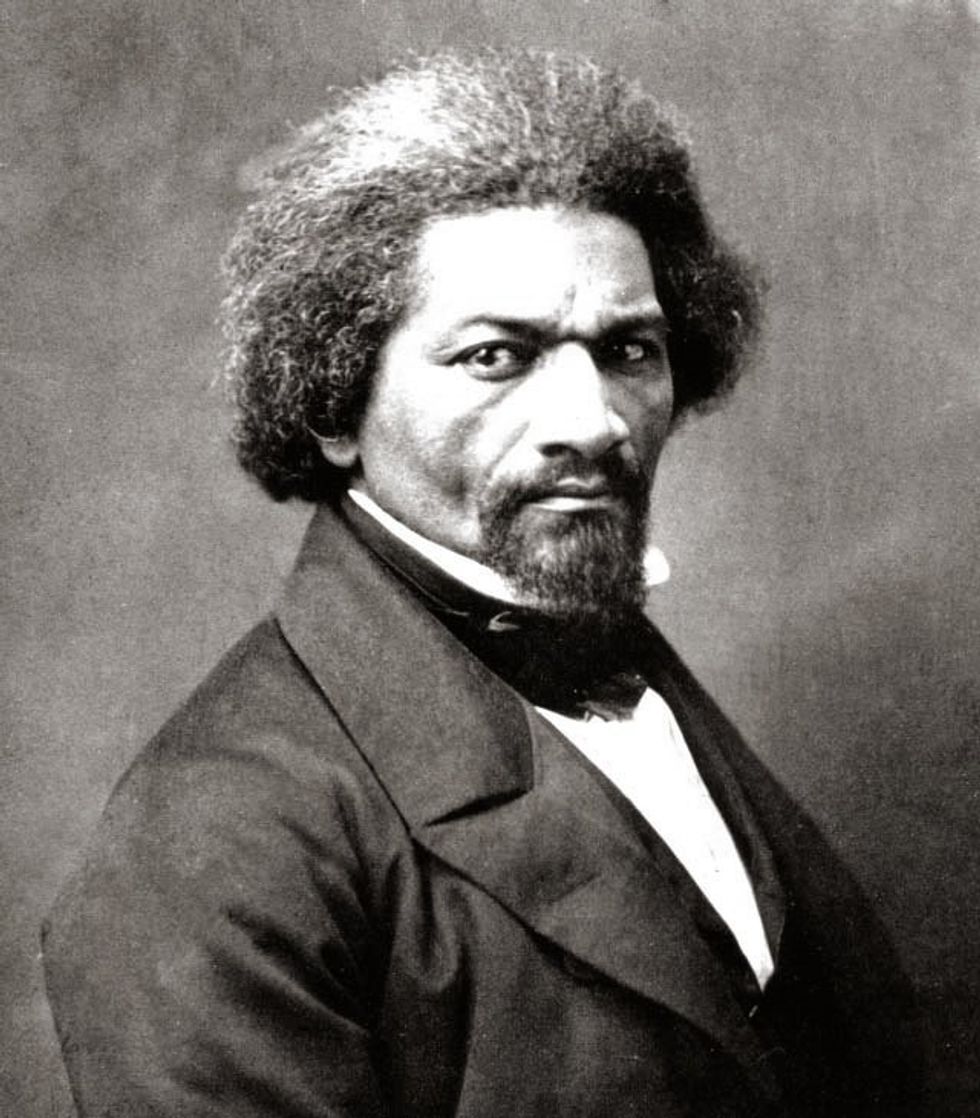

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Wiki Commons

Frederick Douglass, renowned abolitionist and orator, served as the United States minister resident, and consul-general to Haiti and Chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889, appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. However, Douglass resigned in 1891, opposing President Harrison's aggressive territorial ambitions in Haiti. Haiti nonetheless honored Douglass by appointing him as a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the 1892 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His principled stance against imperialism cost him his diplomatic career and underlines the tension Black diplomats still may feel navigating the predominantly white and upper-class U.S. Foreign Service.

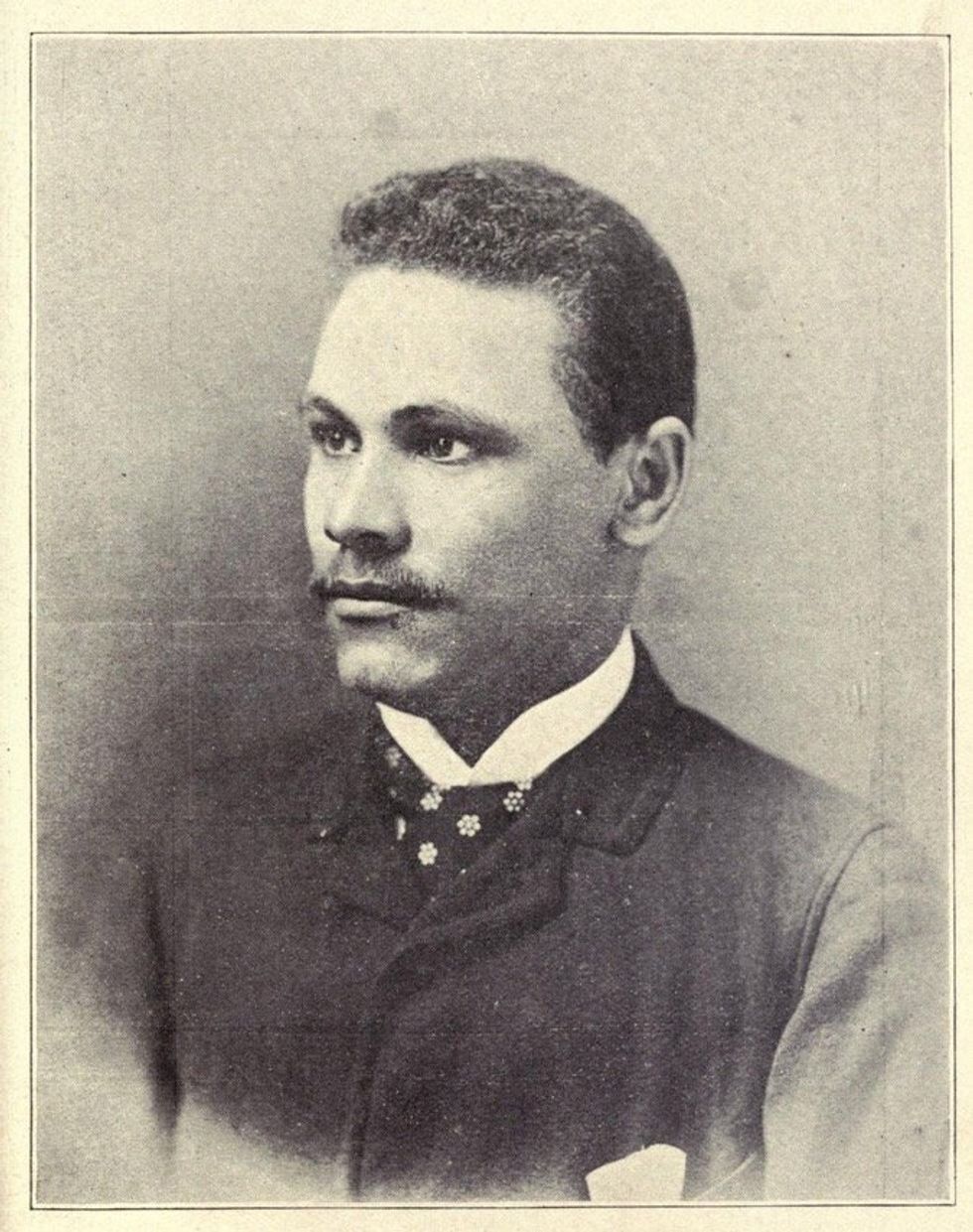

William Henry Hunt

William Henry Hunt

Wiki Commons

Hunt was born into slavery in Tennessee in 1863, the son of Sophia Hunt and the man who enslaved her. Upon emancipation, his mother took him to Nashville, where access to education allowed him to attain a post in the US Consulate in Madagascar eventually. He went on to serve in consular roles spanning from Liberia to France until his retirement on December 31, 1932, pioneering a path for Black diplomats in the 20th century.

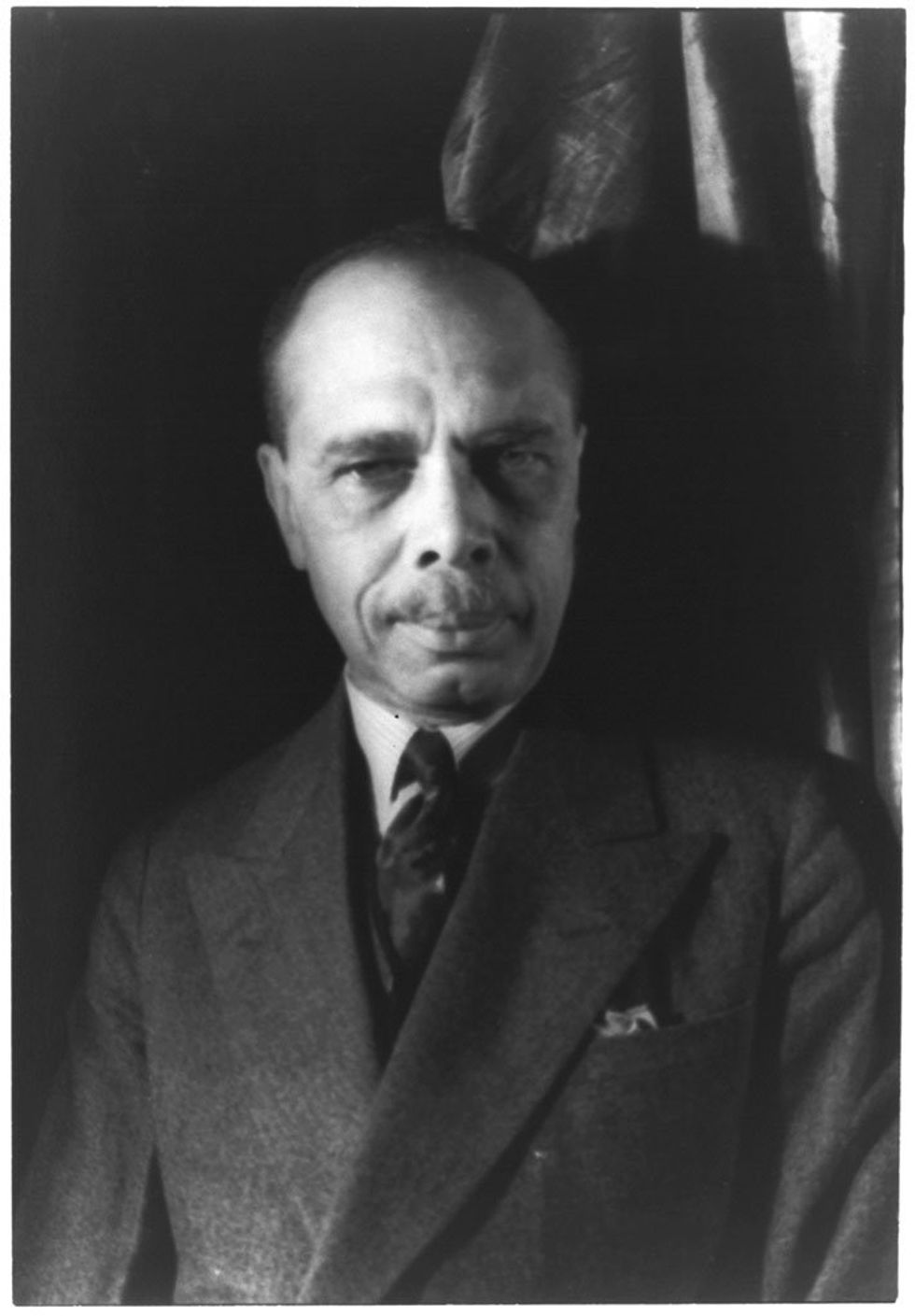

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson

Library of Congress/Flickr Commons

Johnson served as a consul in Venezuela from 1906-1913, under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, he’s best remembered for contributions to the African-American cause that transcended diplomacy. He was a leading figure in the early days of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – effectively its executive officer from 1920 – and wrote “The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man.” He also co-wrote "Lift Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the Black National Anthem, and established the "Daily American," the first Black newspaper.

Ralph Bunche

Anefo photo collection. Dr. Ralph Bunche in Stockholm with the widow of Count Folke Bernadotte. April 10, 1949. Stockholm, Sweden.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Ralph Bunche was arguably the most prominent African American diplomat of the twentieth century. He worked at the State Department from 1943 to 1971, serving under every president from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon. His initial focus on civil rights for African Americans evolved into a global human rights advocacy. He played a pivotal role in the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the adoption of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In 1950, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation efforts in the Palestine conflict, and in 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

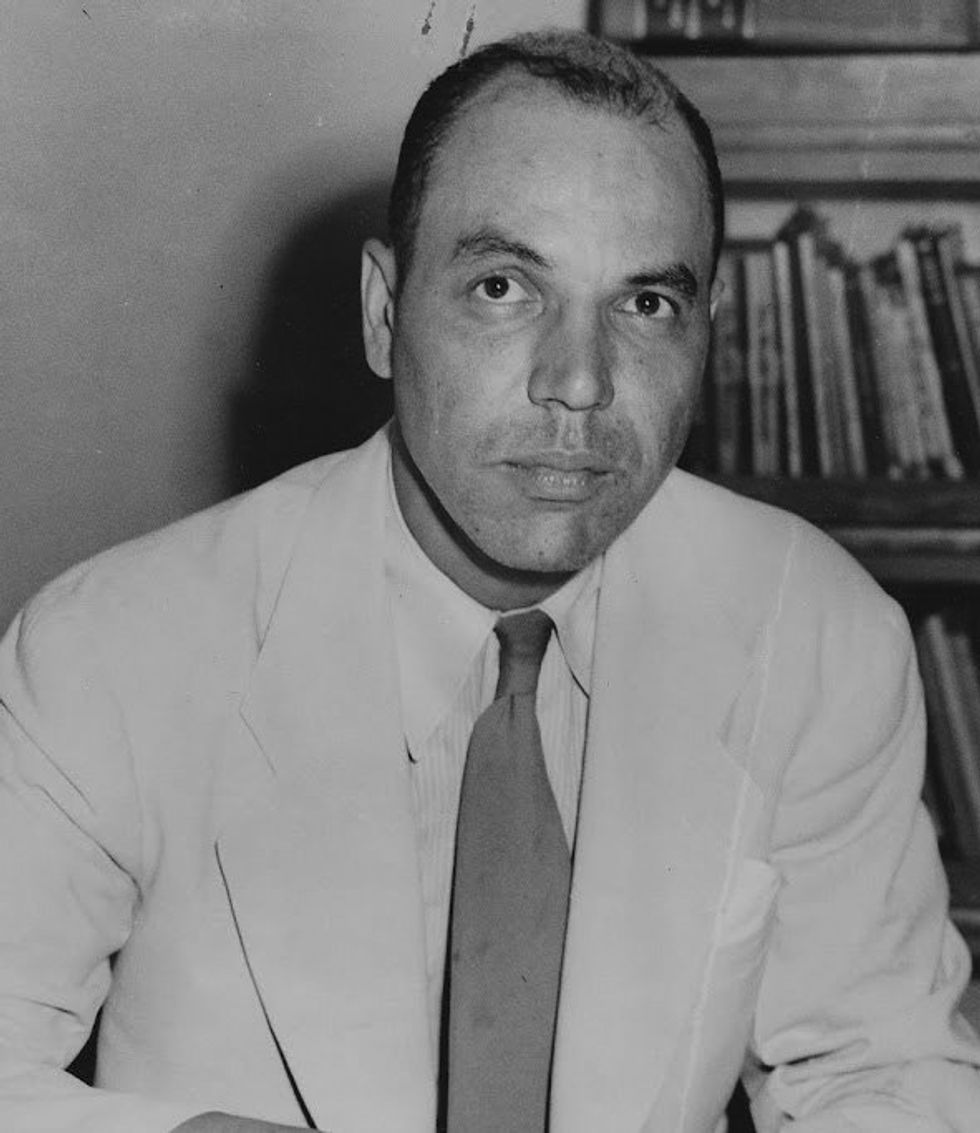

Edward Dudley

Edward Dudley

Fair Use/Flickr

Dudley was named minister to Liberia in 1948 and then an ambassador when the US raised its diplomatic mission to the embassy level the following year under the administration of Harry Truman. During this period, he and a few other Black diplomats were instrumental in the dismantling of the “Negro Circuit”, which limited the Black diplomatic corps to undesirable posts in select countries—often African and predominantly Black countries—while their white counterparts were transferred all over the world.

Clifton R Wharton Sr

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Norway Clifton R. Wharton, Sr., 3:50 PM. President John F. Kennedy sits with US Ambassador to the Kingdom of Norway, Clifton R. Wharton. Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Wharton was the first African American to pass the rigorous Foreign Service examination and benefitted from the advocacy against the “Negro Circuit.” He worked across embassies and consulates around the world. He was the first Black career diplomat to lead a US mission in Europe as Minister to Romania, appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower. Wharton was appointed a US representative to NATO—a first for Black Americans—and a UN delegate. USPS issued a stamp as a tribute to his impeccable service 16 years after he passed.

Carl Rowan

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan, 11:53AM. President John F. Kennedy meets with newly-appointed U.S. Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan right. West Wing Colonnade, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Rowan rose to fame as a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune, writing an acclaimed series about racism in America. He sat and interviewed the most prominent figures in America, including then-Senator John F. Kennedy, on the campaign trail in 1960. Impressed, Kennedy appointed Rowan Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, where he played a crucial role at the United Nations during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Later, he was the first Black director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and, at that time, was the highest-ranking African American in the US government.

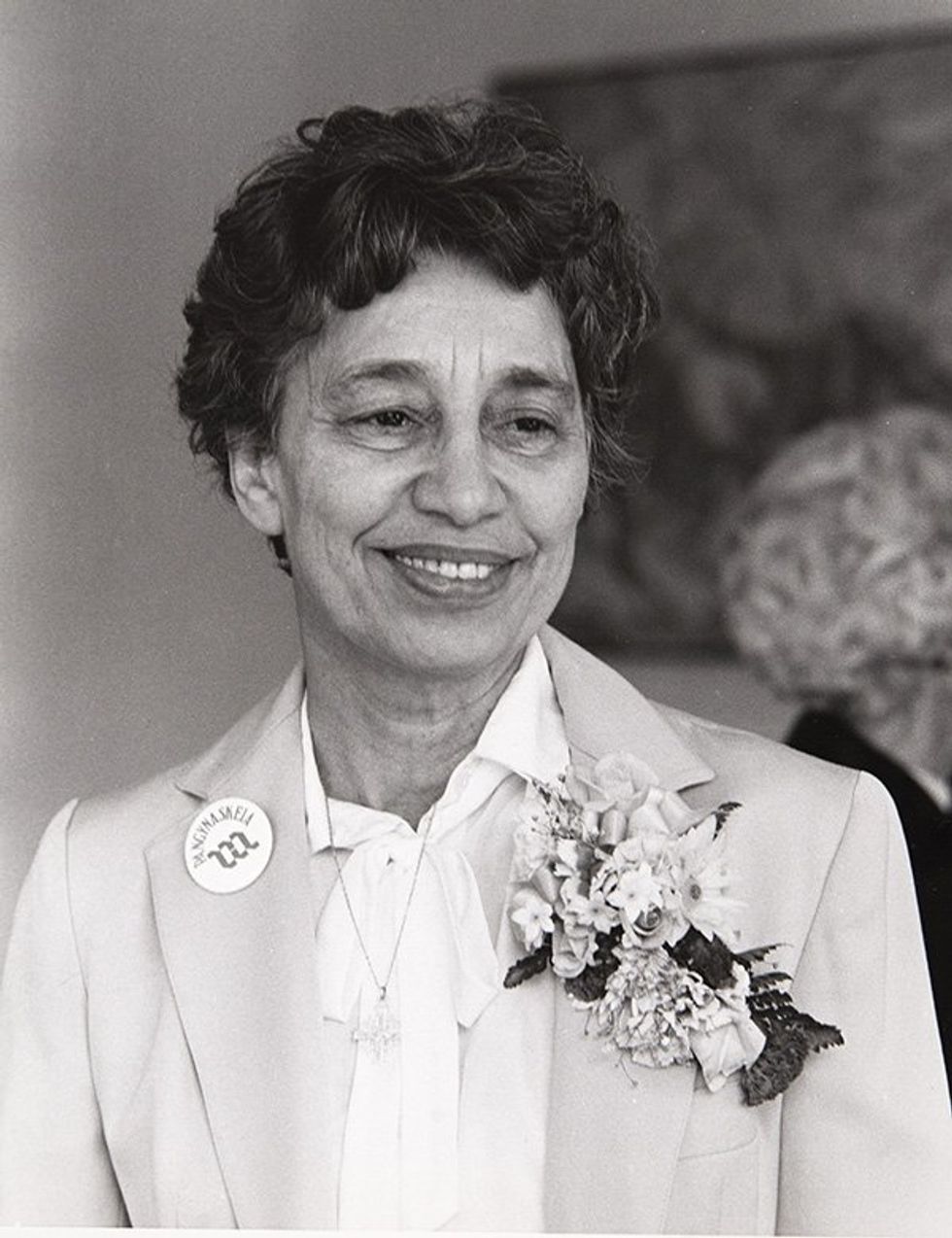

Patricia Roberts Harris

Patricia Roberts Harris

Fair Use/United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

The first African American woman to serve as a US ambassador, Harris served in Luxembourg between 1965-67 under the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. After her tenure, she was nominated as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet in 1977. Her confirmation meant she became the first Black woman to direct a federal department.

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Fair Use/Flickr

Smythe-Haithe was the first Black woman to hold an ambassador position in Africa and the second Black female ambassador during the Carter Administration. Prior to her diplomatic career, she worked with the NAACP on the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case alongside Thurgood Marshall. She also served on the State Department’s Advisory Council for African Affairs under President John F. Kennedy.

Colin Powell

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell makes a point as he testifies May 15, 2001, before the Senate approprations subcommittee for programs of the State Department for the fiscal year 2002.

Reuters

Born in New York to immigrant parents from Jamaica, Powell became the first Black Secretary of State under President George Bush in 2001 after a 35-year career in the military. Powell oversaw foreign policy during the worst national disaster of recent memory, the September 11 attacks. Despite accolades, his tenure was marked by controversy, notably his defense of the 2003 Iraq invasion before the United Nations Security Council. He resigned upon President Bush's 2004 reelection, but his tenure coincided with a surge in black diplomats in the Foreign Service.

Condoleezza Rice

U.S. Secretary of State-designate Condoleezza Rice sits before her U.S. Senate confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, January 18, 2005. Rice vowed to press diplomacy in President Bush's second term after he was criticized for hawkish and unilateral policies in his first four years.

Larry Downing/Reuters

Appointed as National Security Advisor by President George W. Bush in 2002, Rice made history as the second Black person and first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State in 2005. In that role, she advocated for Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza and ceasefire negotiations with Hezbollah in 2005 – though the Bush administration’s legacy in Iraq and Afghanistan dominates memories of her tenure. Under her leadership, the State Department witnessed an increase in Black diplomats, although this progress saw setbacks under President Donald Trump.

- The 1619 Project’s creator Nikole Hannah-Jones discusses its cultural impact ›

- The history of Black women judges in America ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black immigrants in the US ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black representation in the US Congress ›

- Why do Black people feel "erased" from American history? ›

- Ron DeSantis and the latest battle over Black history ›

- Will foreign policy decide the 2024 US election? - GZERO Media ›

- Kamala Harris makes her case - GZERO Media ›

Israeli protesters demonstrate against the right-wing government outside the Knesset in Jerusalem.

Hard Numbers: “Anarchy” in Israel, Michigan State University shooting, the plight of Black mothers and babies, alleged abuses in Portuguese Catholic Church, the new promised land for Scotch

90,000: As Israel’s Knesset began a contentious debate over Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s proposed judicial reforms on Monday, a whopping 90,000 people hit the streets of Jerusalem to protest against the measures, with another 100,000 joining demonstrations nationwide. Netanyahu accused his opponents of “pushing the country to anarchy.” Here’s more from GZERO on the back story.

3: At least three people were killed, and five injured, when a gunman opened fire at Michigan State University on Monday night. The assailant then turned the gun on himself. It is the latest in a string of mass shootings on college campuses and schools across the country in recent years.

87: New data on US childbirths shows that, even when correcting for income, Black mothers and their babies fare worse than white ones. The infant mortality rate for rich Black mothers is 87 points higher than that for poor White mothers, according to a decade-long study, which was conducted in California.

4,815: A new report commissioned by the Portuguese Catholic Church alleges that its priests and other authority figures sexually abused at least 4,815 children over the past seven decades. The investigating commission says this number is merely the “tip of the iceberg.” But under Portuguese law, only 25 of those cases are recent enough to be prosecuted.

219 million: India is now the world’s leading importer of Scotch by volume, taking in 219 million bottles of the stuff last year. An increase of some 60% over 2021 helped to push India past France for the top spot. Still, billion-strong India remains a tiny part of the global scotch market — the industry hopes that a long-awaited UK-India trade deal could help to crack things open more.Biden’s promise to name a Black woman to SCOTUS isn’t unprecedented

US President Joe Biden has gotten pushback from some Republicans for honoring his campaign pledge to nominate a Black woman to replace outgoing Justice Breyer on the Supreme Court.

But for Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Clarence Page, how is that different from when Ronald Reagan promised to pick the court's first woman in Sandra Day O'Connor?

"Biden isn't saying that just being black is enough, or just being a woman is enough. I think they've got to be qualified first," he tells Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

Page believes the three names that have come forth on the president's shortlist are all qualified. It's too bad, he says, that they can be stigmatized by those who think they will get the job because of their race.

Watch this episode of GZERO World with Ian Bremmer: Black voter suppression in 2022

- The history of Black voting rights in America - GZERO Media ›

- Why do Black people feel "erased" from American history? - GZERO ... ›

- The Graphic Truth: SCOTUS vacancies in presidential election years ... ›

- Biden's SCOTUS pick to replace Breyer must appeal to Senate ... ›

- SCOTUS confirmation hearings no longer serve a purpose - GZERO Media ›

Nikole Hannah-Jones blames backlash against 1619 Project, CRT on the myth of US "exceptionalism"

Why is there such a strong conservative reaction to the 1619 Project and critical race theory?

For Nikole Hannah-Jones, the New York Times journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for her work as creator of the 1619 Project, a big part of the problem is that we, "as Americans, are deeply, deeply invested in this mythology of exceptionalism.

"We really are indoctrinated into this idea that these intrepid colonists broke off from [...] Great Britain so that they could advance the ideas of liberty and individual rights. And to believe in that, then you have to downplay the role of slavery."

In other words, she adds, you must gloss over the fact that America has been "plagued by racism and inequality from our beginning."

What Hannah-Jones calls the white backlash against that narrative, she says, should not surprise us. Even after the horrific killing of George Floyd, which could have been an inflection point, Hannah-Jones laments, some politicians seized the opportunity to divide us even further on race.

"How do we divide these people who were finding common cause in Black equality? And you do that by saying, you know, we, we believe, you know, what happened to George Floyd was wrong, but it's gone too far now. Now they're trying to make you feel like there's something wrong with your whiteness. Now they're taking away your icons, they're knocking down your statues and they want to tell your children that your children are evil."

Watch this episode of GZERO World with Ian Bremmer: Counter narrative: Black Americans, the 1619 Project, and Nikole Hannah-Jones

Nikole Hannah-Jones: America chose slavery — and benefited from it

Many people today still think US slavery was only prevalent in the South. They are wrong, says Nikole Hannah-Jones. All 13 colonies had slaves upon America's independence.

It's not just that the Founding Fathers were slave-owners, which we all know. Slave labor, the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times journalist points out, powered the US Industrial Revolution by producing cheap cotton for textiles.

"We've kind of tried to section slavery off as if it was just in the realm of the backwards South, but this wasn't American endeavor and our nascent capitalism, [which] was really built on the institution of slavery."

In her view and that of the 1619 Project she created, slavery is central to the American story because it wasn't accidental at all.

"We did not need slavery to be successful, but we chose slavery. And that led to our success in many ways."

Watch this clip from her interview with Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

Watch the full episode of GZERO World with Ian Bremmer: Counter narrative: Black Americans, the 1619 Project, and Nikole Hannah-Jones

Why do Black people feel "erased" from American history?

Growing up, New York Times journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones only learned a little about the plight of Black people in America during Black History Month. The Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of the 1619 Project studied some usual suspects such as Harriet Tubman or Frederick Douglass, and then discussed slavery to cover the Civil War.

But then Black people like herself, she says, vanish from the narrative until the civil rights movement.

“There was no really larger understanding of how Black Americans fit into the larger story of America. And there certainly wasn't the teaching of Black people as actors in the American story."

For Hannah-Jones, this explains why white Americans don't know what it means "to be erased" from US history as well as broader American culture and literature.

"That erasure is really demeaning, and it's really powerful.”

Watch this episode of GZERO World with Ian Bremmer: Counter narrative: Black Americans, the 1619 Project, and Nikole Hannah-Jones

- US global reputation a year after George Floyd's murder; EU ... ›

- Nikole Hannah-Jones pushes back against "disqualifying" 1619 ... ›

- Breathing while Black: WaPo's Karen Attiah on racial injustice ... ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black representation in the US Congress ... ›

- The history of Black voting rights in America - GZERO Media ›

- The problem with China’s Zero COVID strategy | GZERO World Podcast - GZERO Media ›

- Pioneering Black American leaders in US foreign policy - GZERO Media ›

- How will the summer of 2024 be remembered in US history? - GZERO Media ›

- Yuval Noah Harari explains why the world isn't fair (but could be) - GZERO Media ›