GZERO North

Does Canada need to prepare for a US attack?

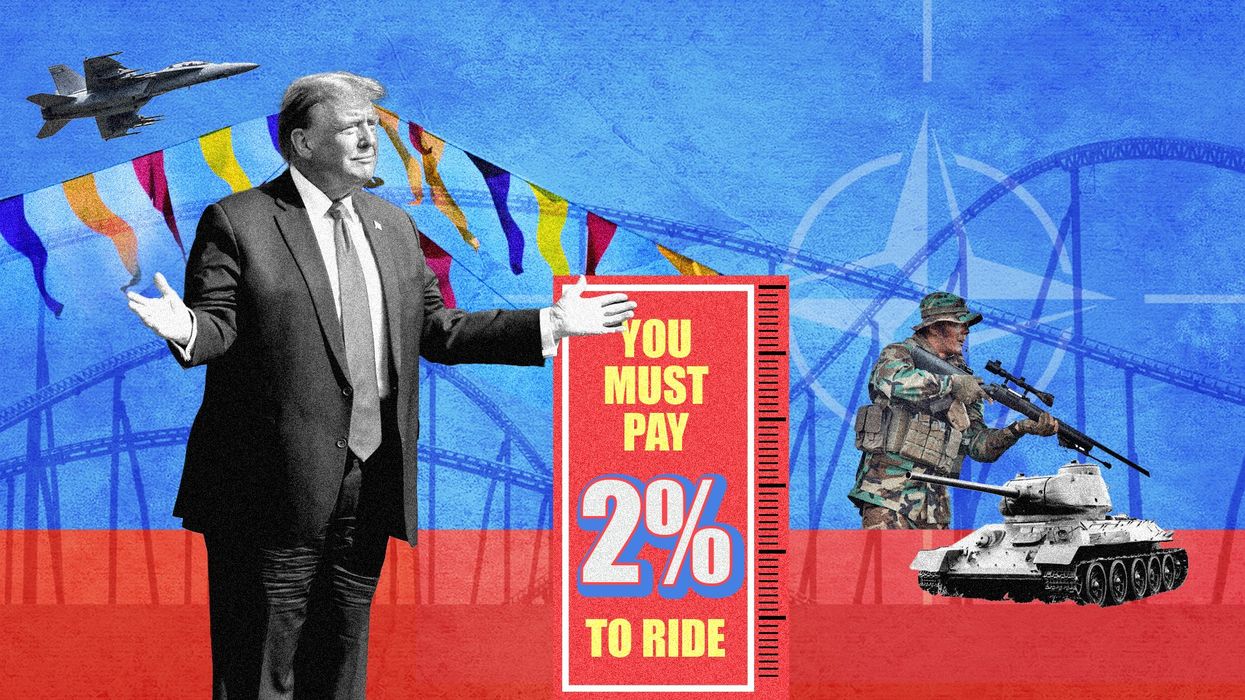

Canada has begun thinking the unthinkable: how to defend against a US attack. It suddenly realizes — far too late – that the 2% GDP goal on defense spending is no longer aspirational but urgent. But what kind of military does it need? To find out, GZERO Publisher Evan Solomon spoke with retired Vice Admiral Mark Norman, the former vice chief of defense staff in Canada and currently a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

Mar 13, 2025