GZERO North

Is Canada set for a snap election?

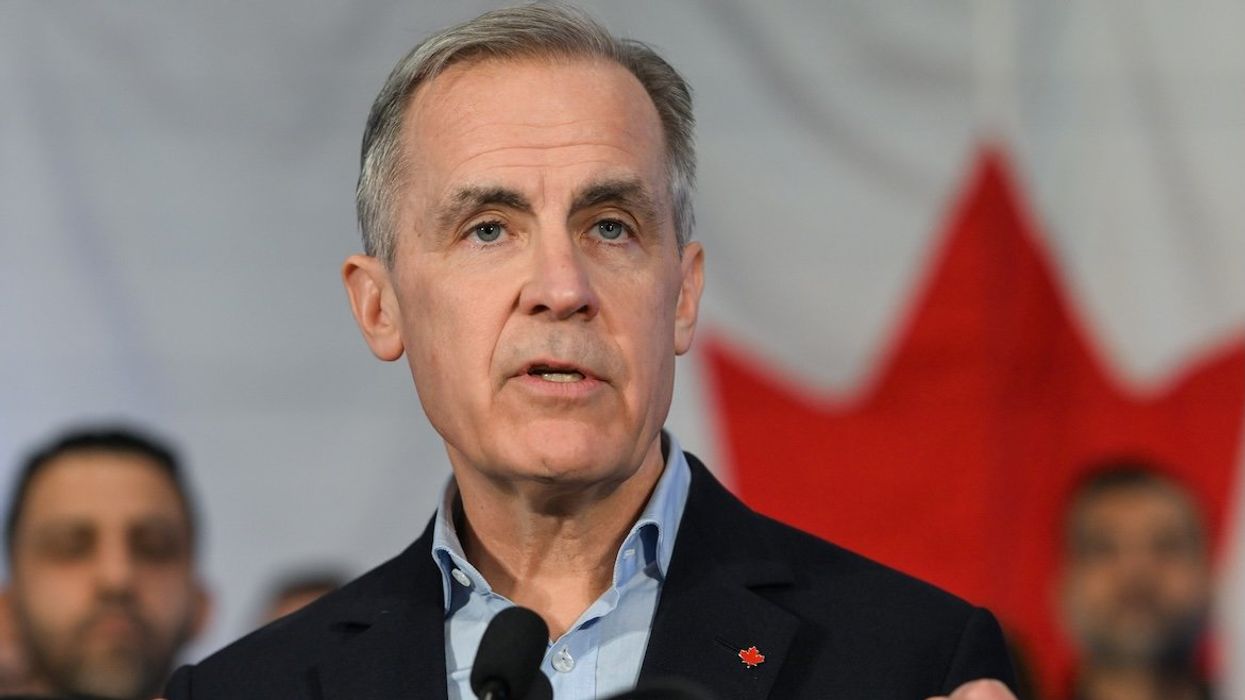

An internal memo from Canada’s New Democratic Party is warning candidates to prepare for a federal election call as early as March 10. The memo suggests that if former Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney becomes leader of the Liberal Party on March 9, he might announce an election the next day and send Canadians to the polls this spring.

Feb 13, 2025