Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

Georgia’s next target: LGBTQ+ freedoms

Pride Month is sure to look different in Georgia this year – and may soon disappear forever.

This week, the Eurasian country – not the US state – introduced legislation aimed at curtailing civil liberties for LGBTQ+ people. The draft text includes a ban on same-sex marriages, same-sex adoptions, gender-affirming care, endorsement of same-sex relationships at gatherings and educational institutions, plus any same-sex depictions in media.

Over a decade ago, the South Caucasus republic became one of the few post-Soviet states to enshrine anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination into law. So, why the 180-degree change?

The Georgian Dream ruling party, in power since 2012, has been slowly shifting the country’s alignment away from Brussels and toward Moscow. This year, thousands protested Georgia Dream’s foreign agent law, which opponents say is identical to a law used by the Kremlin to crush dissent. Huge demonstrations and a presidential veto couldn’t stop the bill from passing.

But don’t expect mass protests against the similarly Kremlin-aligned anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. Tbilisi has repeatedly canceled Pride Marches after right-wing protesters violently stormed the celebrations, and much of Georgia’s majority Orthodox Christian society is likely to support the measures in the name of national and religious identity.

Tinatin Japaridze, a Georgian-born regional analyst at Eurasia Group, says the Georgian Dream party is pushing this legislation to serve them politically and shore up conservative support.

Without a strong coalition to oust Georgian Dream, she says “they will continue to adopt and adapt the Russian playbook in a way that they hope will keep them in power for as long as possible.”

Condoleezza Rice

Pioneering Black American leaders in US foreign policy

Who exactly are the people representing America to the world? Chances are they’re “pale, male, and Yale”, as the saying goes. Even in 2024, the US Foreign Service – especially in senior positions – doesn’t look like the rest of America. African Americans, people of color, and women continue to encounter barriers to influential roles.

However, some Black diplomats — like UN Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield — have broken this racial ceiling and helped reimagine what an American envoy can be. Her predecessors, through the sweep of US history, encountered discrimination and racism both domestically and abroad and left an indelible mark on US foreign policy. To mark the end of Black History Month, GZERO highlights the stories of a select few:

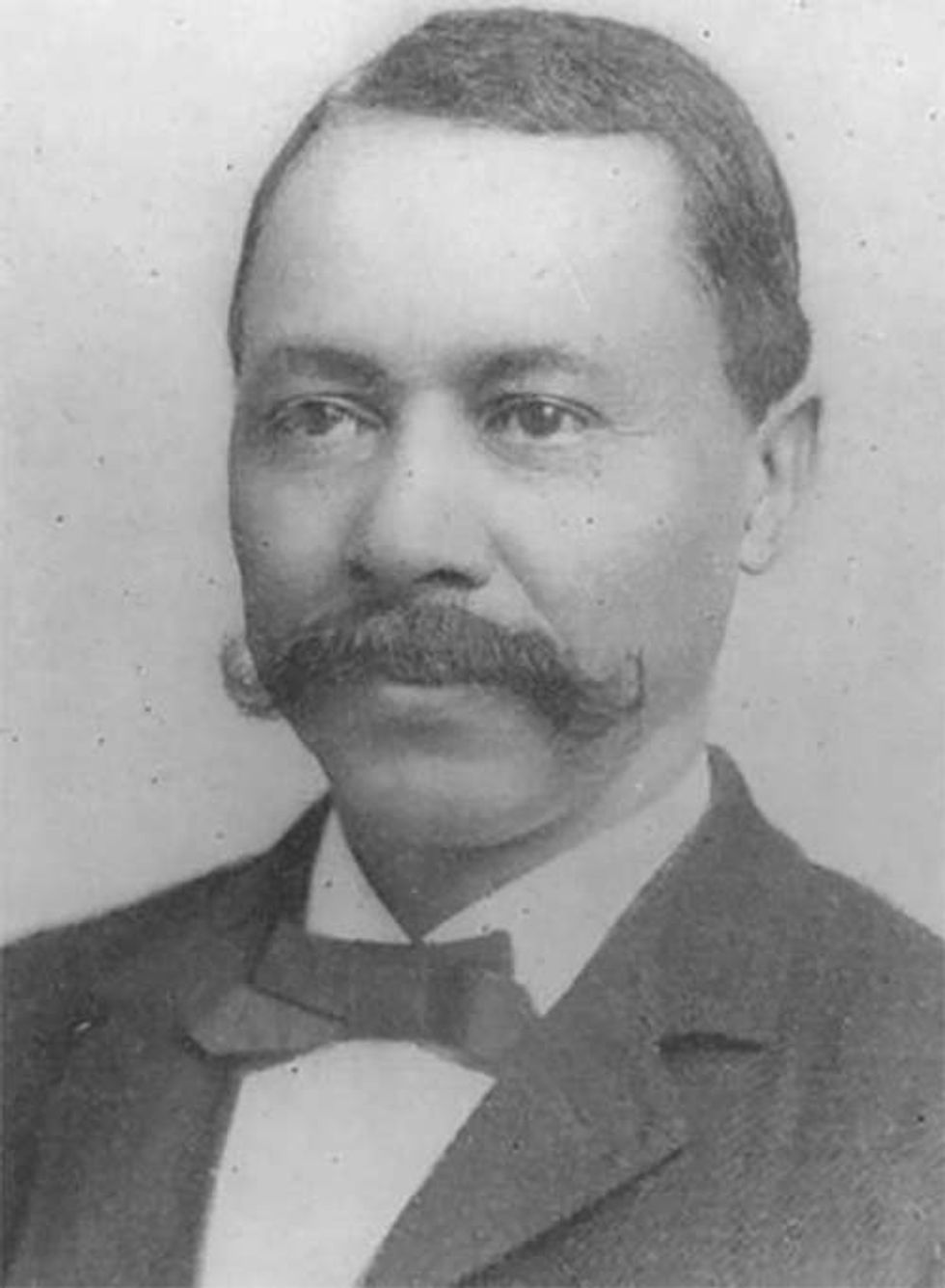

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Fair Use/National Museum of American Diplomacy

Born into a free Black family in Connecticut in 1833, Bassett broke racial barriers from the very onset of his career. He was the first Black student admitted to the Connecticut Normal School and taught at the pioneering Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia in the years before the Civil War.

His impassioned polemics for abolition and equal rights during the war thrust him into the political spotlight. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him minister to Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 1869, Basset became the first African American to serve as a diplomat anywhere in the world. Upon his return to the United States, he served as American Consul General for Haiti in New York City.

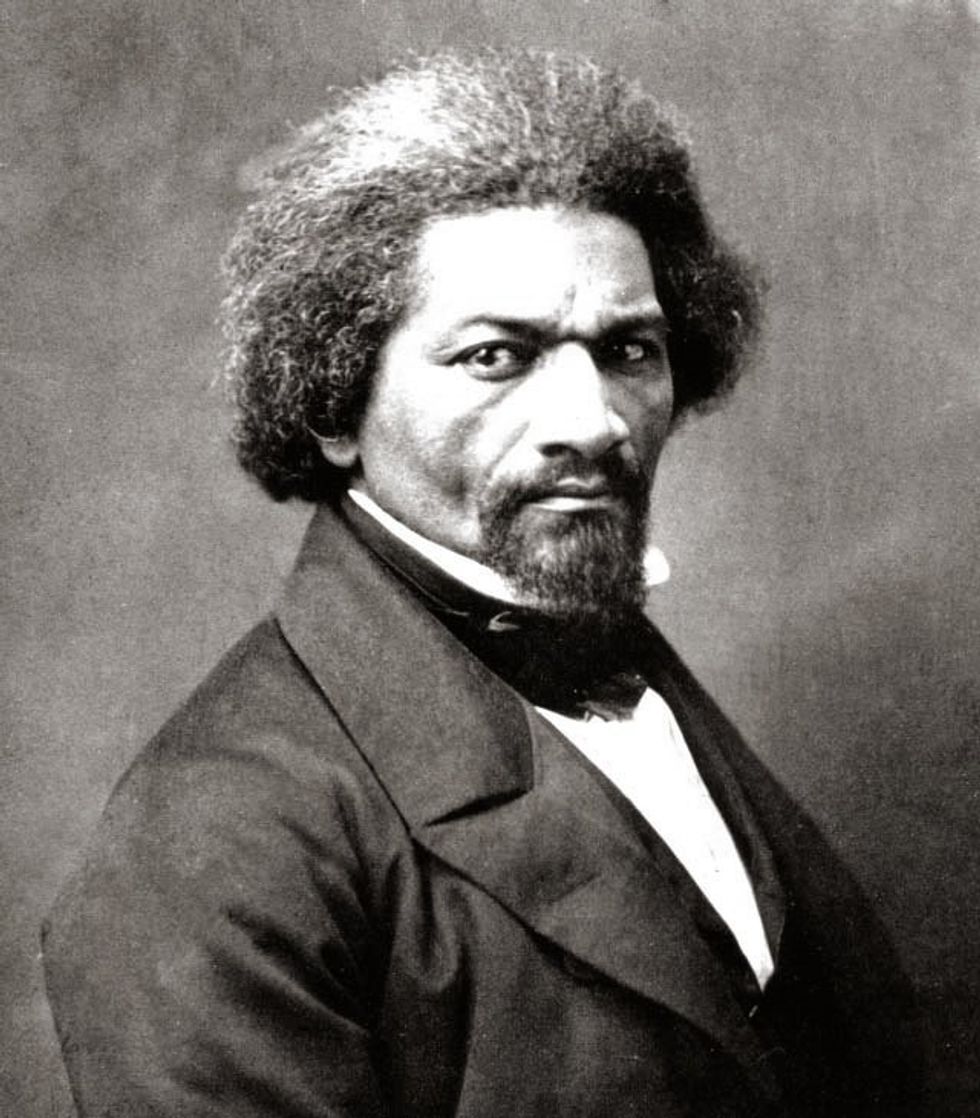

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Wiki Commons

Frederick Douglass, renowned abolitionist and orator, served as the United States minister resident, and consul-general to Haiti and Chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889, appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. However, Douglass resigned in 1891, opposing President Harrison's aggressive territorial ambitions in Haiti. Haiti nonetheless honored Douglass by appointing him as a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the 1892 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His principled stance against imperialism cost him his diplomatic career and underlines the tension Black diplomats still may feel navigating the predominantly white and upper-class U.S. Foreign Service.

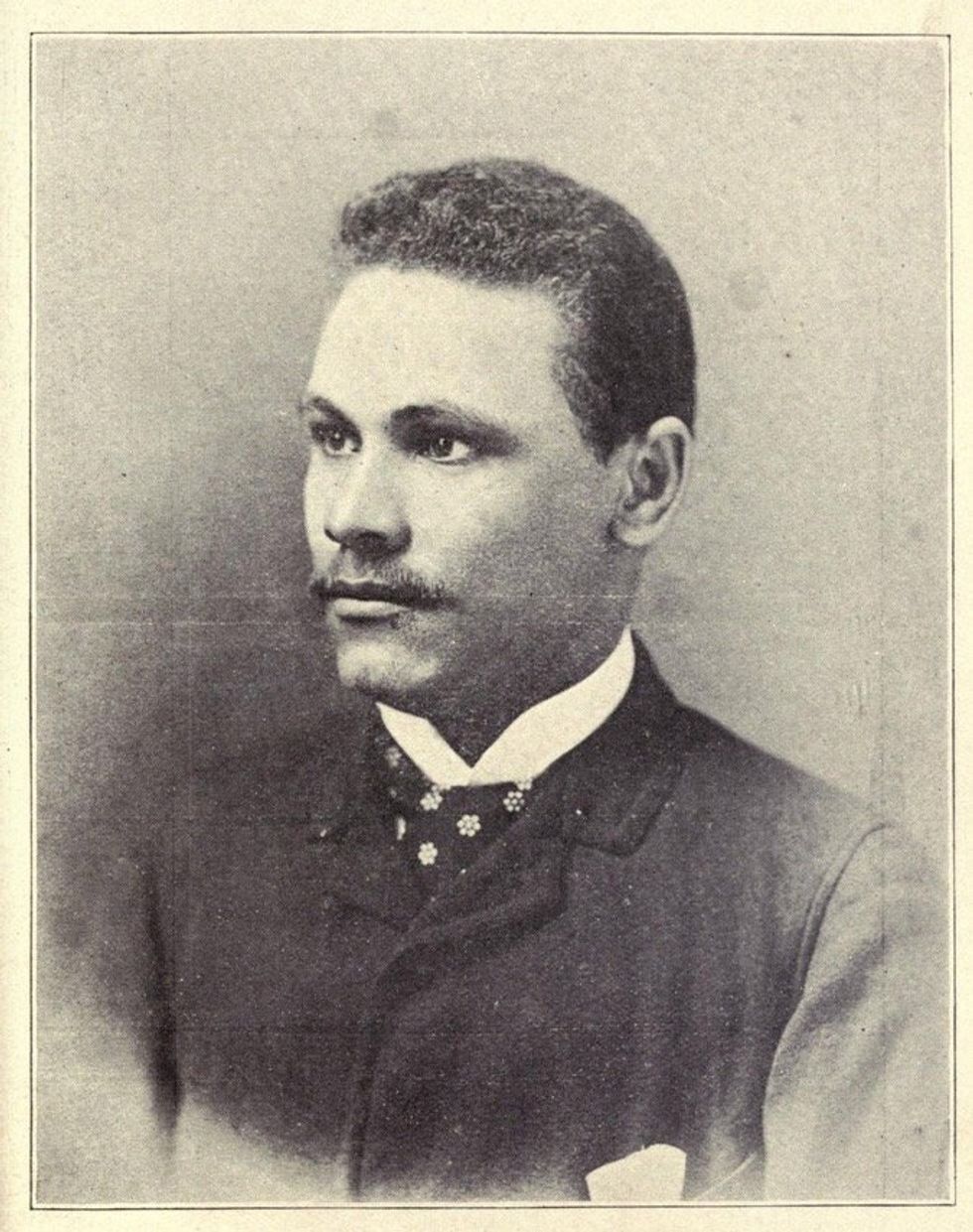

William Henry Hunt

William Henry Hunt

Wiki Commons

Hunt was born into slavery in Tennessee in 1863, the son of Sophia Hunt and the man who enslaved her. Upon emancipation, his mother took him to Nashville, where access to education allowed him to attain a post in the US Consulate in Madagascar eventually. He went on to serve in consular roles spanning from Liberia to France until his retirement on December 31, 1932, pioneering a path for Black diplomats in the 20th century.

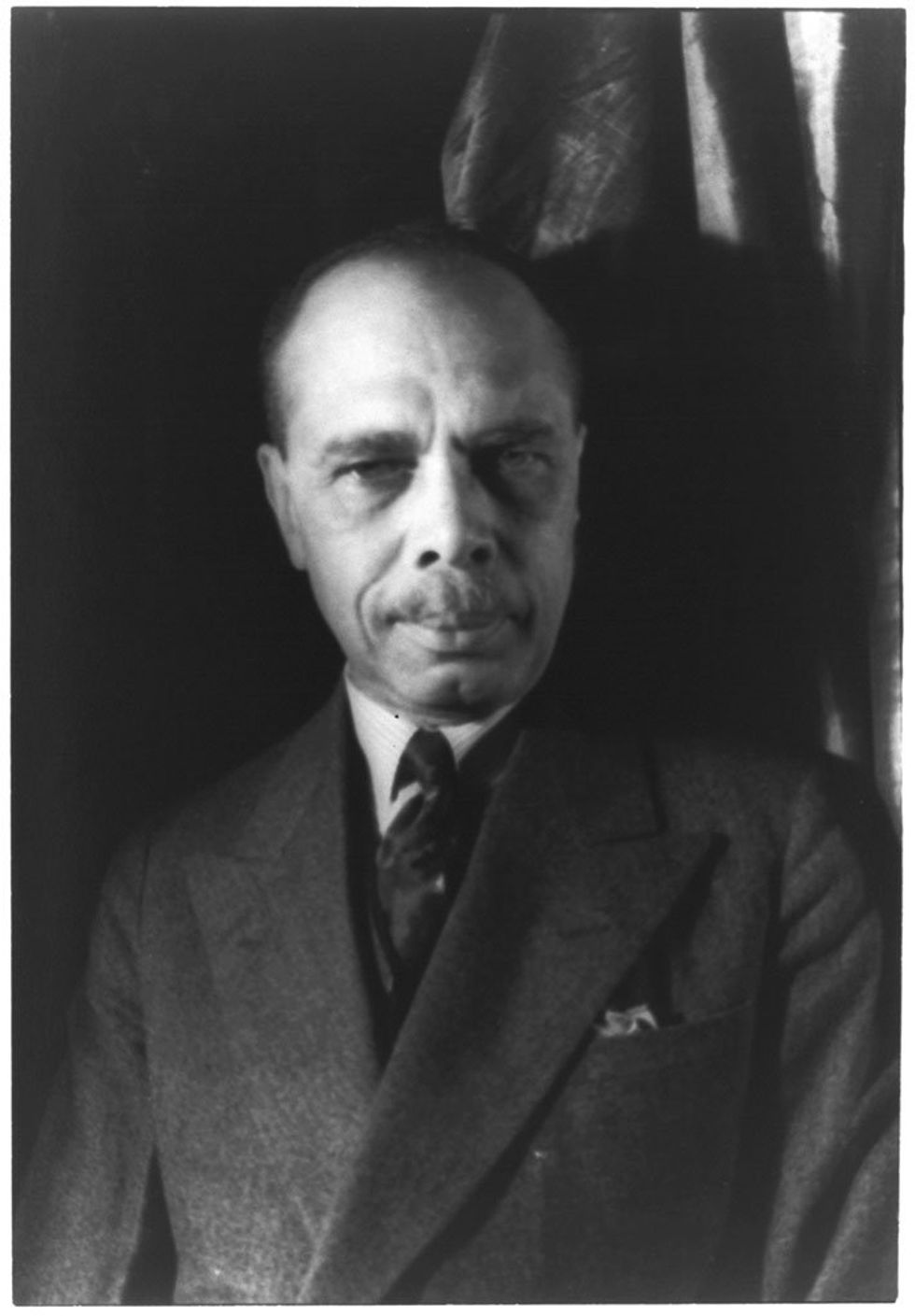

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson

Library of Congress/Flickr Commons

Johnson served as a consul in Venezuela from 1906-1913, under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, he’s best remembered for contributions to the African-American cause that transcended diplomacy. He was a leading figure in the early days of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – effectively its executive officer from 1920 – and wrote “The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man.” He also co-wrote "Lift Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the Black National Anthem, and established the "Daily American," the first Black newspaper.

Ralph Bunche

Anefo photo collection. Dr. Ralph Bunche in Stockholm with the widow of Count Folke Bernadotte. April 10, 1949. Stockholm, Sweden.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Ralph Bunche was arguably the most prominent African American diplomat of the twentieth century. He worked at the State Department from 1943 to 1971, serving under every president from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon. His initial focus on civil rights for African Americans evolved into a global human rights advocacy. He played a pivotal role in the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the adoption of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In 1950, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation efforts in the Palestine conflict, and in 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

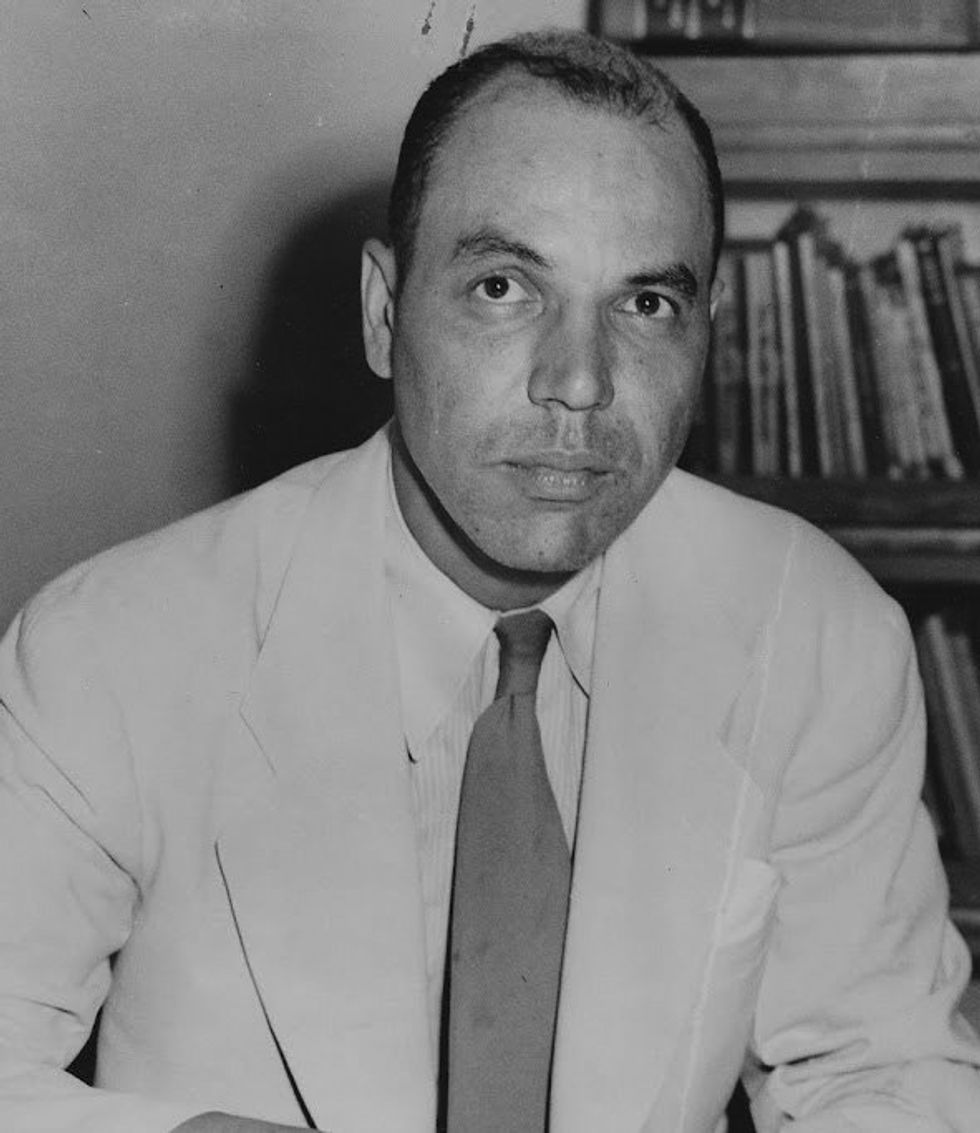

Edward Dudley

Edward Dudley

Fair Use/Flickr

Dudley was named minister to Liberia in 1948 and then an ambassador when the US raised its diplomatic mission to the embassy level the following year under the administration of Harry Truman. During this period, he and a few other Black diplomats were instrumental in the dismantling of the “Negro Circuit”, which limited the Black diplomatic corps to undesirable posts in select countries—often African and predominantly Black countries—while their white counterparts were transferred all over the world.

Clifton R Wharton Sr

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Norway Clifton R. Wharton, Sr., 3:50 PM. President John F. Kennedy sits with US Ambassador to the Kingdom of Norway, Clifton R. Wharton. Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Wharton was the first African American to pass the rigorous Foreign Service examination and benefitted from the advocacy against the “Negro Circuit.” He worked across embassies and consulates around the world. He was the first Black career diplomat to lead a US mission in Europe as Minister to Romania, appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower. Wharton was appointed a US representative to NATO—a first for Black Americans—and a UN delegate. USPS issued a stamp as a tribute to his impeccable service 16 years after he passed.

Carl Rowan

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan, 11:53AM. President John F. Kennedy meets with newly-appointed U.S. Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan right. West Wing Colonnade, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Rowan rose to fame as a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune, writing an acclaimed series about racism in America. He sat and interviewed the most prominent figures in America, including then-Senator John F. Kennedy, on the campaign trail in 1960. Impressed, Kennedy appointed Rowan Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, where he played a crucial role at the United Nations during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Later, he was the first Black director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and, at that time, was the highest-ranking African American in the US government.

Patricia Roberts Harris

Patricia Roberts Harris

Fair Use/United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

The first African American woman to serve as a US ambassador, Harris served in Luxembourg between 1965-67 under the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. After her tenure, she was nominated as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet in 1977. Her confirmation meant she became the first Black woman to direct a federal department.

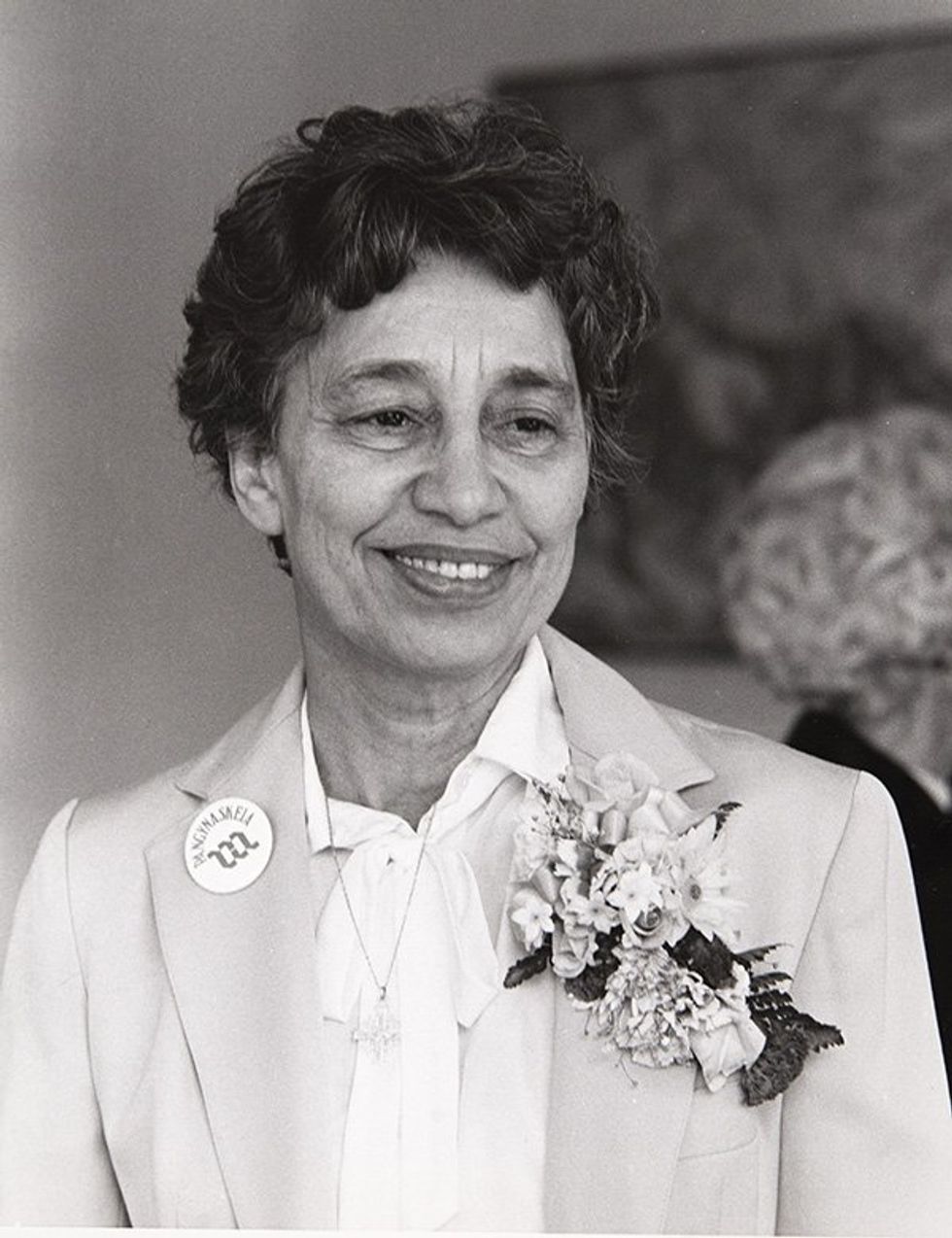

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Fair Use/Flickr

Smythe-Haithe was the first Black woman to hold an ambassador position in Africa and the second Black female ambassador during the Carter Administration. Prior to her diplomatic career, she worked with the NAACP on the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case alongside Thurgood Marshall. She also served on the State Department’s Advisory Council for African Affairs under President John F. Kennedy.

Colin Powell

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell makes a point as he testifies May 15, 2001, before the Senate approprations subcommittee for programs of the State Department for the fiscal year 2002.

Reuters

Born in New York to immigrant parents from Jamaica, Powell became the first Black Secretary of State under President George Bush in 2001 after a 35-year career in the military. Powell oversaw foreign policy during the worst national disaster of recent memory, the September 11 attacks. Despite accolades, his tenure was marked by controversy, notably his defense of the 2003 Iraq invasion before the United Nations Security Council. He resigned upon President Bush's 2004 reelection, but his tenure coincided with a surge in black diplomats in the Foreign Service.

Condoleezza Rice

U.S. Secretary of State-designate Condoleezza Rice sits before her U.S. Senate confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, January 18, 2005. Rice vowed to press diplomacy in President Bush's second term after he was criticized for hawkish and unilateral policies in his first four years.

Larry Downing/Reuters

Appointed as National Security Advisor by President George W. Bush in 2002, Rice made history as the second Black person and first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State in 2005. In that role, she advocated for Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza and ceasefire negotiations with Hezbollah in 2005 – though the Bush administration’s legacy in Iraq and Afghanistan dominates memories of her tenure. Under her leadership, the State Department witnessed an increase in Black diplomats, although this progress saw setbacks under President Donald Trump.

- The 1619 Project’s creator Nikole Hannah-Jones discusses its cultural impact ›

- The history of Black women judges in America ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black immigrants in the US ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black representation in the US Congress ›

- Why do Black people feel "erased" from American history? ›

- Ron DeSantis and the latest battle over Black history ›

- Will foreign policy decide the 2024 US election? - GZERO Media ›

- Kamala Harris makes her case - GZERO Media ›

Activists descend on Washington, DC, to mark the 60th anniversary of MLK's "I have a dream" speech.

The March on Washington, 60 years later

Sixty years ago on Monday, over a quarter of a million people gathered in Washington, DC, for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, a century after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream Speech,” galvanizing supporters of the Civil Rights Movement.

The march was initially conceived 20 years prior by labor leader Philip Randolph when African Americans were excluded from the job creation programs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. By the late 1950s, with the Civil Rights Act stalled in Congress, Dr. King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference were also planning to march on Washington for freedom.

Together, they planned a march to capitalize on the growing grassroots support and outrage over racial inequality in the US. The massive turnout, in conjunction with a decade of other peaceful protests for civil rights, convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Act into law in 1964. The following year, he signed the National Voting Rights Act of 1965. Together, these bills outlawed discrimination against people of color and women, effectively ended segregation, and made discriminatory voting practices illegal.

This weekend, thousands gathered in Washington to commemorate the march’s 60th anniversary. The day was filled with speeches from civil rights leaders and activists reminding the nation of its unfinished work on equality. I attended and was struck by how intergenerational but connected the crowd was – alumni of HBCUs were embraced by current students, and older members of Black fraternities and sororities reminisced with new members. Like an echo, the words “go vote” were exchanged in lieu of “goodbye.”

Yolanda King, Dr. King’s 15-year-old granddaughter, told the crowd, “If I could speak to my grandfather today, I would say, I’m sorry we still have to be here to rededicate ourselves to finishing your work and ultimately realizing your dream,” she said. “Today, racism is still with us. Poverty is still with us. And now, gun violence has come for places of worship, our schools, and our shopping centers.”

Leaders of other social movements also gave speeches, from Parkland survivor and March for Our Lives founder David Hogg, to Planned Parenthood CEO Alexis McGill Johnson. In the aftermath of the Supreme Court overturning Affirmative Action and Roe v. Wade, all of the speakers warned that the progress of the civil rights movement could be reversed.

“We’ve come a long way in the 60 years since MLK stood on those steps, " said Albert Williams, a civil rights activist who attended Saturday’s march and the original in 1963, “but black communities throughout the world are still in a state of emergency today.”

GZERO reporter Riley Callanan was on hand this weekend for the commemorative march in Washington, DC.

Harry Belafonte attends the “Sing Your Song” premiere in New York in 2011.

The beloved Harry Belafonte

Born in Harlem in 1927, Harry Belafonte’s voice carried around the world.

You can read about his meteoric rise and his importance in the American civil rights movement here. He died in New York on Tuesday.

My first memory of Belafonte was the song “Day-O,” also known as “The Banana Boat Song.” As a small child, I loved that song. My mother had an album of his music, and I listened to “Day-O” over and over and over and over and over.

Later, I was delighted to see him perform it on TV. The rhythm and melody seemed playful and joyous, and Belafonte’s megawatt smile multiplied the effect. A happy man belting out a happy song.

At some older age, I began to finally listen to and absorb the lyrics.

Work all night on a drink of rum

Daylight come and we want go home

Stack banana 'til the morning come

Daylight come and we want go home

Come Mister tally man, tally me banana

Daylight come and we want go home

Lift six foot, seven foot, eight foot bunch

Daylight come and we want go home

A beautiful bunch of ripe banana

Daylight come and we want go home

Hide the deadly black tarantula

Daylight come and we want go home

Harry Belafonte was a man with an overflow of charisma, grace, beauty, and God-given talent. He was a warrior for justice. Not just for his people, but for all people.

And his was a voice and expression so clear that small children listened to and loved him.

– Willis Sparks

Facebook civil rights audit; TikTok in Hong Kong

Nicholas Thompson, editor-in-chief of WIRED, provides his perspective on technology news:

Will the new audit of Facebook civil rights practices change the way the company operates?

Yes. It came under a lot of pressure from civil rights activists who organized an advertising boycott. And then an internal audit on Facebook's effect on civil rights came out. It was quite critical. Those two things, one after the other, will surely lead to changes at the company.

What is happening with TikTok in Hong Kong?

Well, China passed its oppressive new security law in Hong Kong. All the tech companies are suddenly in a difficult situation. To comply with the law, violating some of your fundamental principles or do you withdraw? Most of them are delaying. TikTok acted quickly but that was an easy choice for them and their parent company, ByteDance, which already owns a TikTok competitor in China.

Is Quibi officially a bust?

Not yet, but they really, really, really need a hit.