Economy

A new attitude and a new budget: Can the Tories make a comeback?

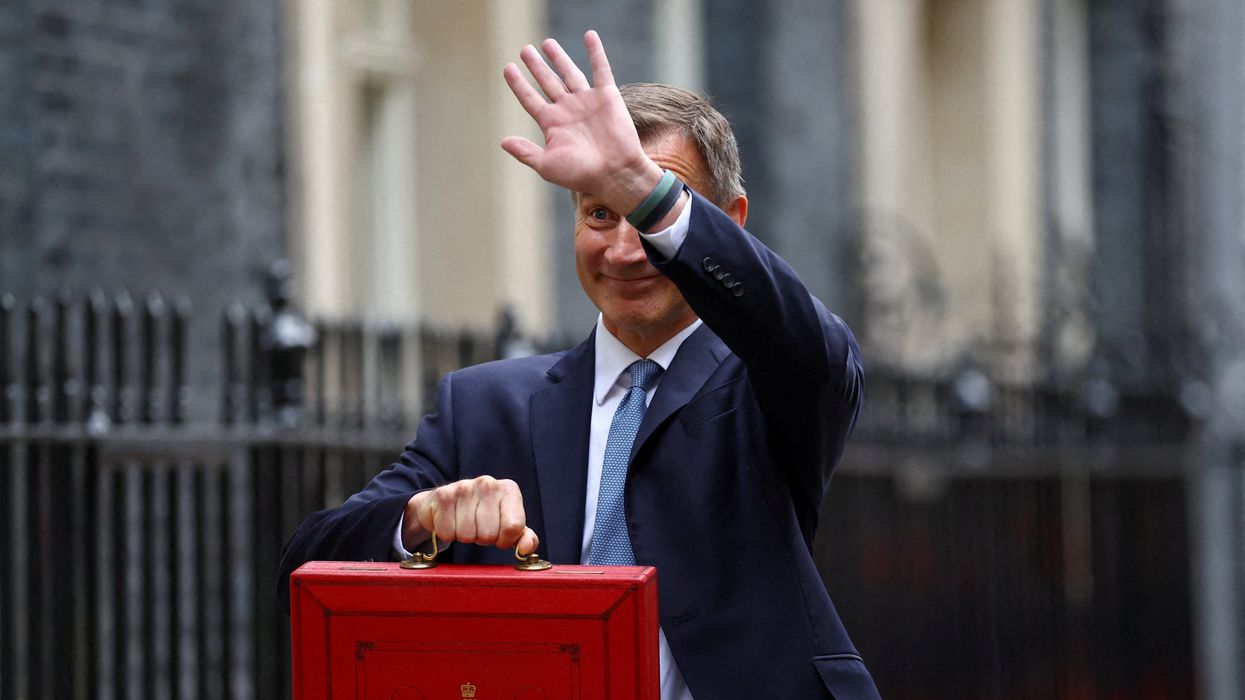

Weeks after the International Monetary Fund forecast that the UK will be the worst-performing advanced economy this year, British Chancellor Jeremy Hunt on Wednesday handed down a fresh national budget.

Mar 15, 2023