What We're Watching

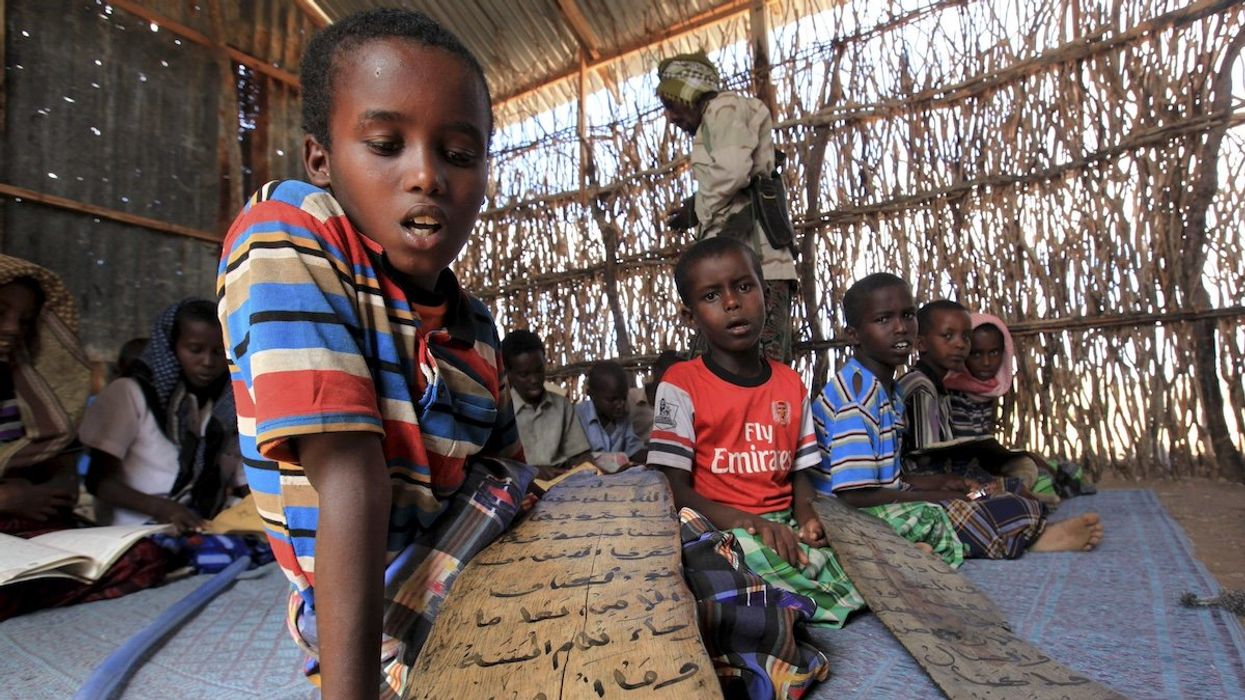

African leaders gather to hear Beijing’s pitch

Leaders from 50 African nations are expected to gather in Beijing on Wednesday for the 9th triennial China-Africa Cooperation summit — aimed at deepening strategic coordination between China and Africa – but China’s ongoing economic woes have shifted the tone considerably.

Sep 03, 2024