Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

dissent

Mamuka Mdinaradze, leader of the ruling Georgian Dream party's parliamentary faction, is punched in the face by opposition MP Aleko Elisashvili during discussion of the bill on "foreign agents" in the Parliament, Tbilisi, Georgia, April 15, 2024 in this still image taken from a live broadcast video.

Georgia’s parliament advances divisive foreign agents bill

Georgia’s ruling party, Georgian Dream, on Wednesday advanced a controversial “foreign agents” bill that rights groups say could be used to stifle civil society and silence political opponents.

The bill, which has sparked street violence and a parliamentary fistfight, would require any organization receiving 20% of its funding from abroad to register as a foreign agent.

Critics call it the “Russian law” because it mimics legislation the Kremlin has used to silence dissent in Russia. Georgian Dream and its billionaire founder, who made his fortune in Russia, are often seen as sympathetic to Moscow. The Kremlin denies any connection to the bill.

Georgian Dream says the law is like the US Foreign Agents Registration Act, aka FARA. But while FARA primarily focuses on government lobbyists, the Georgian law targets any organizations that have foreign funding. The EU, meanwhile, says the bill violates democratic norms, and warned that its passage would “negatively impact Georgia’s progress” in joining the bloc.

The bill, which must still pass two more readings before becoming law, is “very damaging for Georgia’s image and for Western support of Georgia,” says Tinatin Japaridze, a Georgian-born analyst at Eurasia Group.

It’s a sign, she says, that the former Soviet republic is at risk of tilting in the “direction of being under Moscow’s influence yet again,” particularly if Georgian Dream retains control after October’s crucial parliamentary elections.

Tracking anti-Navalny bot armies

In an exclusive investigation into online disinformation surrounding online reaction to Alexei Navalny's death, GZERO asks whether it is possible to track the birth of a bot army. Was Navalny's tragic death accompanied by a massive online propaganda campaign? We investigated, with the help of a company called Cyabra.

Alexei Navalny knew he was a dead man the moment he returned to Moscow in January 2021. Vladimir Putin had already tried to kill him with the nerve agent Novichok, and he was sent to Germany for treatment. The poison is one of Putin’s signatures, like pushing opponents out of windows or shooting them in the street. Navalny knew Putin would try again.

Still, he came home.

“If your beliefs are worth something,” Navalny wrote on Facebook, “you must be willing to stand up for them. And if necessary, make some sacrifices.”

He made the ultimate sacrifice on Feb. 16, when Russian authorities announced, with Arctic banality, that he had “died” at the IK-3 penal colony more than 1,200 miles north of Moscow. A frozen gulag. “Convict Navalny A.A. felt unwell after a walk, almost immediately losing consciousness,” they announced as if quoting a passage from Koestler’s “Darkness at Noon.” Later, deploying the pitch-black doublespeak of all dictators, they decided to call it, “sudden death syndrome.”

Worth noting: Navalny was filmed the day before, looking well. There is no body for his wife and two kids to see. No autopsy.

As we wrote this morning, Putin is winning on all fronts. Sensing NATO support for the war in Ukraine is wavering – over to you, US Congress – Putin is acting with confident impunity. His army is gaining ground in Ukraine. He scored a propaganda coup when he toyed with dictator-fanboy Tucker Carlson during his two-hour PR session thinly camouflaged as an “interview.” And just days after Navalny was declared dead, the Russian pilot Maksim Kuzminov, who defected to Ukraine with his helicopter last August, was gunned down in Spain.

And then, of course, there is the disinformation war, another Putin battleground. Navalny’s death got me wondering if there would be an orchestrated disinformation campaign around the event, and if so, whether there was any way to track it? Would there be, say, an online release of shock bot troops to combat Western condemnation of Navalny’s death and blunt the blowback?

It turns out there was.

To investigate, GZERO asked the “social threat information company” Cyabra, which specializes in tracking bots, to look for disinformation surrounding the online reactions to the news about Navalny. The Israeli company says its job is to uncover “threats” on social platforms. It has built AI-driven software to track “attacks such as impersonation, data leakage, and online executive perils as they occur.”

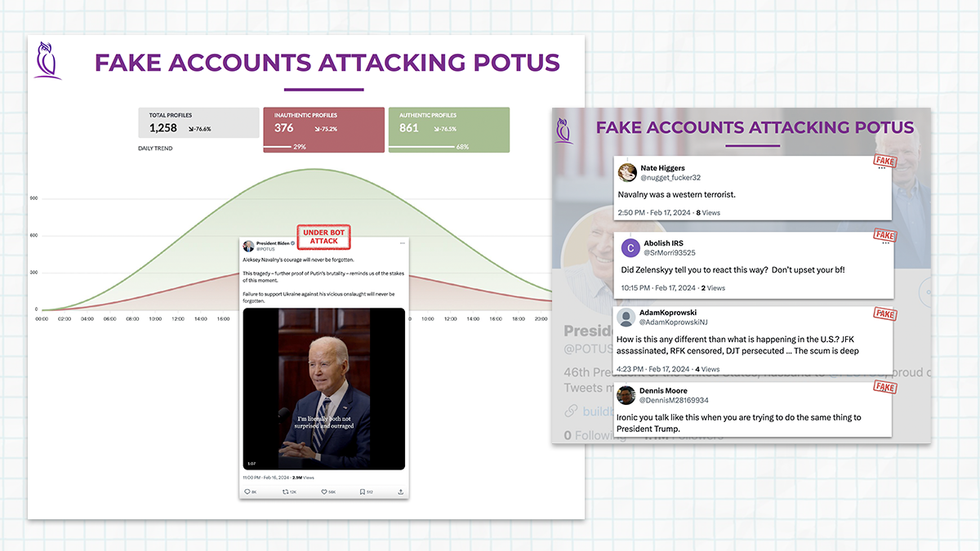

Cyabra’s team focused on the tweets President Joe Bidenand Prime Minister Justin Trudeau posted condemning Navalny’s death. Their software analyzed the number of bots that targeted these official accounts. And what they found was fascinating.

According to Cyabra, “29% of the Twitter profiles interacting with Biden’s post about Navalny on X were identified as inauthentic.” For Trudeau, the number was 25%.

Courtesy of Cyabra

Courtesy of Cyabra

So, according to Cyabra, more than a quarter of the reaction you saw on X related to Navalny’s death and these two leaders’ reactions came from bots, not humans. In other words, a bullshit campaign of misinformation.

This finding raises a lot of questions. What’s the baseline of corruption to get a good sense of comparison? For example, is 27% bot traffic on Biden’s tweet about Navalny’s death a lot, or is everything on social media flooded with the same amount of crap? How does Cyabra's team actually track bots, and how accurate is their data? Are they missing bots that are well-disguised, or, on the other side, are some humans being labeled as “inauthentic”? In short, what does this really tell us?

In the year of elections, with multiple wars festering and AI galloping ahead of regulation, the battle against disinformation and bots is more consequential than ever. The bot armies of the night are marching. We need to find a torch to see where they are and if there are any tools that can help us separate fact from fiction.

Tracking bot armies is a job that often happens in the shadows, and it comes with a lot of challenges. Can this be done without violating people’s privacy? How hard is this to combat? I spoke with the CEO of Cyabra, Dan Brahmy, to get his view.

Solomon: When Cyabra tracked the reactions to the tweets from President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau about the “death” of Navalny, you found more than 25% of the accounts were inauthentic. What does this tell us about social media and what people can actually trust is real?

Brahmy: From elections to sporting events to other significant international headline events, social media is often the destination for millions of people to follow the news and share their opinion. Consequently, it is also the venue of choice for malicious actors to manipulate the narrative.

This was also the case when Cyabra looked into President Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau’s X post directly blaming Putin for Navalny’s death. These posts turned out to be the ideal playing ground for narrative-manipulating bots. Inauthentic accounts on a large scale attacked Biden and Trudeau and blamed them for their foreign and domestic policies while attempting to divert attention from Putin and the negative narrative surrounding him.

The high number of fake accounts detected by Cyabra, together with the speed at which those accounts engaged in the conversation to divert and distract following the announcement of Navalny’s death, shows the capabilities of malicious actors and their intentions to conduct sophisticated influence operations.

Solomon: Can you tell where these are from and who is doing it?

Brahmy: Cyabra monitors for publicly available information on social media and does not track IP addresses or any private information. The publicly shared location of the account is collected by Cyabra. When analyzing the Navalny conversation, Cyabra saw that the majority of the accounts claimed themselves as coming from the US.

Solomon: There is always the benchmark question: How much “bot” traffic or inauthentic traffic do you expect at any time, for any online event? Put the numbers we see here for Trudeau and Biden in perspective.

Brahmy: The average percentage of fake accounts participating in an everyday conversation online typically varies between 4 and 8%. Cyabra’s discovery of 25-29% fake accounts related to this conversation is alarming, significant, and should give us cause for concern.

Solomon: Ok, then there is the accuracy question. How do you actually identify a bot and how do you know, given the sophistication of AI and new bots, that you are not missing a lot of them? Is it easier to find “obvious bots”— i.e., something that tweets every two minutes 24 hours a day, then say, a series of bots that look and act very human?

Brahmy: Using advanced AI and machine learning, Cyabra analyzes a profile’s activity and interactions to determine if it demonstrates non-human behaviors. Cyabra’s proprietary algorithm consists of over 500 behavioral parameters. Some parameters are more intuitive, like the use of multiple languages, while others require in-depth expertise and advanced machine learning. Cyabra’s technology works at scale and in almost real-time.

Solomon: There is so much disinformation anyway – actual people who lie, mislead, falsify, scam – how much does this matter?

Brahmy: The creation and activities of fake accounts on social media (whether it be a bot, sock puppet, troll, or otherwise) should be treated with the utmost seriousness. Fake accounts are almost exclusively created for nefarious purposes. By identifying inauthentic profiles and then analyzing their behaviors and the false narratives they are spreading, we can understand the intentions of malicious actors and remedy them as a society.

While we all understand that the challenge of disinformation is pervasive and a threat to society, being able to conduct the equivalent of an online CT scan reveals the areas that most urgently need our attention.

Solomon: Why does it matter in a big election year?

Brahmy: More than 4 billion people globally are eligible to vote in 2024, with over 50 countries holding elections. That’s 40% of the world’s population. Particularly during an election year, tracking disinformation is important – from protecting the democratic process, ensuring informed decision-making, preventing foreign interference, and promoting transparency, to protecting national security. By tracking and educating the public on the prevalence of inauthentic accounts, we slowly move closer to creating a digital environment that fosters informed, constructive, and authentic discourse.

You can check out part of the Cybara report here.

- Understanding Navalny’s legacy inside Russia ›

- Navalny’s widow continues his fight for freedom ›

- “A film is a weapon on time delay” — an interview with “Navalny” director Daniel Roher ›

- Navalny's death is a huge loss for democracy - NATO's Mircea Geona ›

- Alexei Navalny's death: A deep tragedy for Russia ›

- Navalny's death is a message to the West ›

- Navalny’s death: Five things to know ›