GZERO World Clips

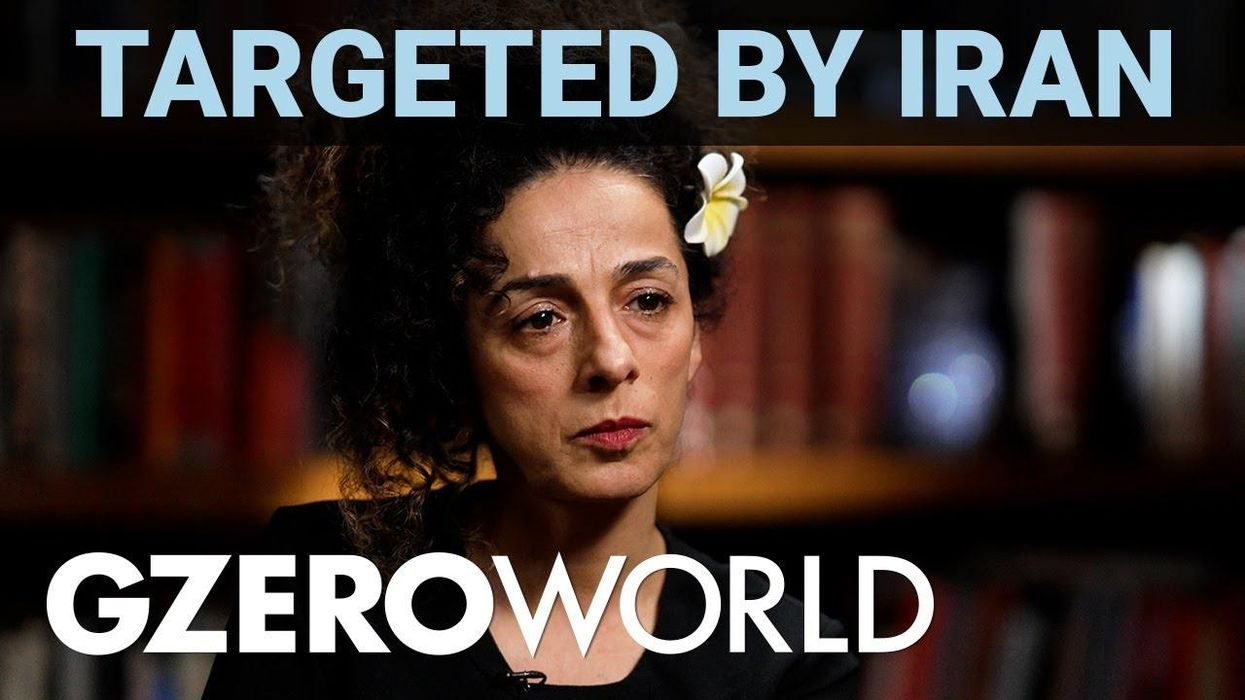

Masih Alinejad lives in Brooklyn. Iran wants to kill her.

Iranian journalist and activist Masih Alinejad has long been in Tehran's crosshairs, accused of being an agent of the United States. She denies it. "I'm not an American agent. I have agency," Alinejad tells Ian Bremmer on GZERO World.

Dec 20, 2022