Munich Security Conference

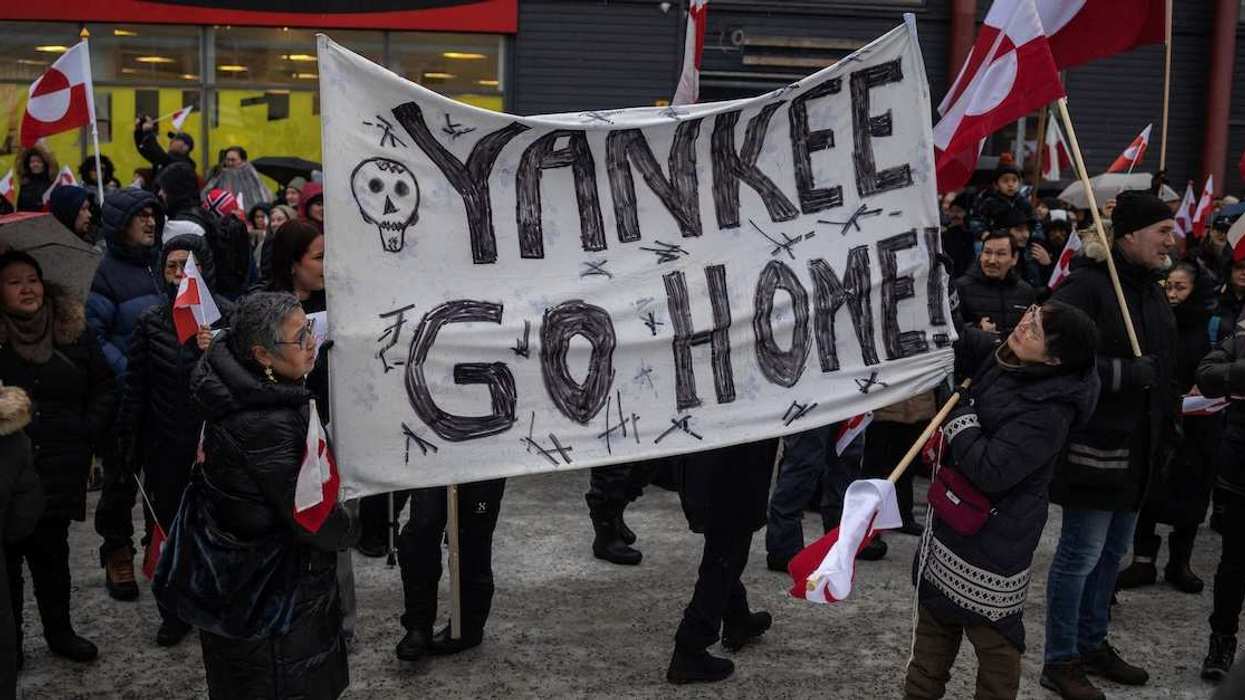

Are we in an era of "wrecking ball politics?"

At the 62nd Munich Security Conference in Munich, GZERO’s Tony Maciulis spoke with Benedikt Franke, Vice Chairman and CEO of the Munich Security Conference, to discuss whether the post-1945 global order is under strain or already unraveling.

Feb 12, 2026