GZERO World Clips

AI is already discovering new cures

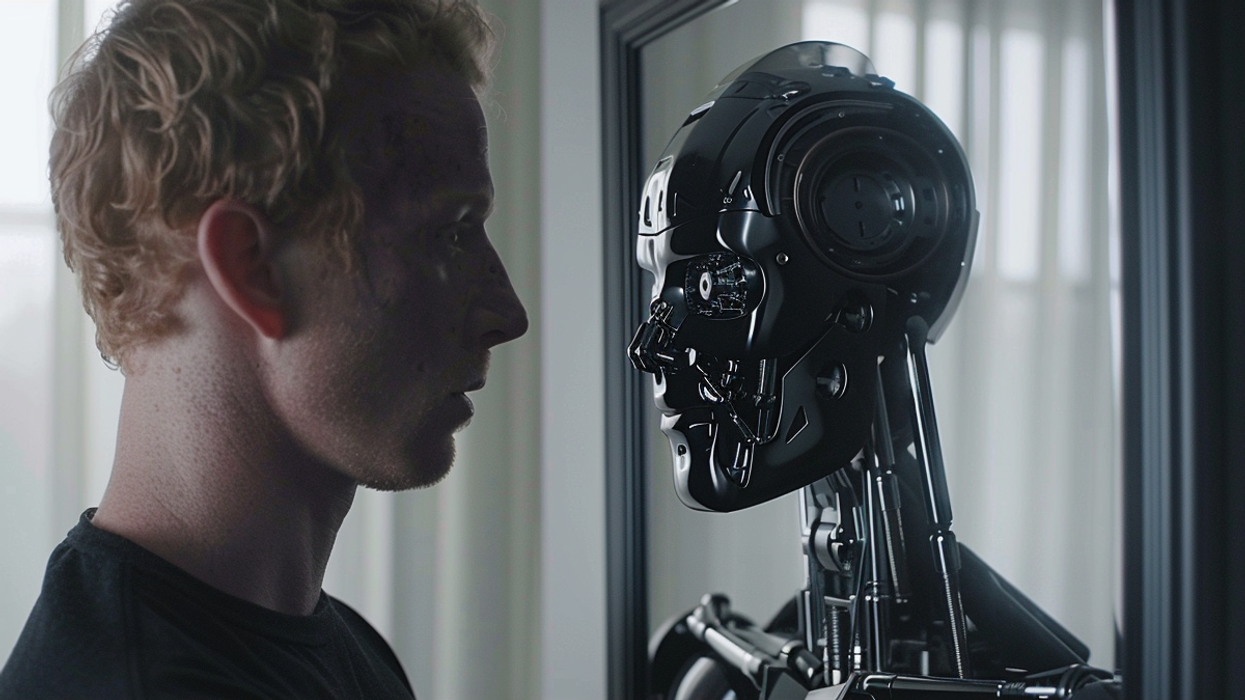

Siddhartha Mukherjee explains how AI is designing entirely new medicines—molecules that may have never existed—by learning the rules of chemistry and generating drugs with unprecedented speed and precision.

Sep 08, 2025