GZERO World Clips

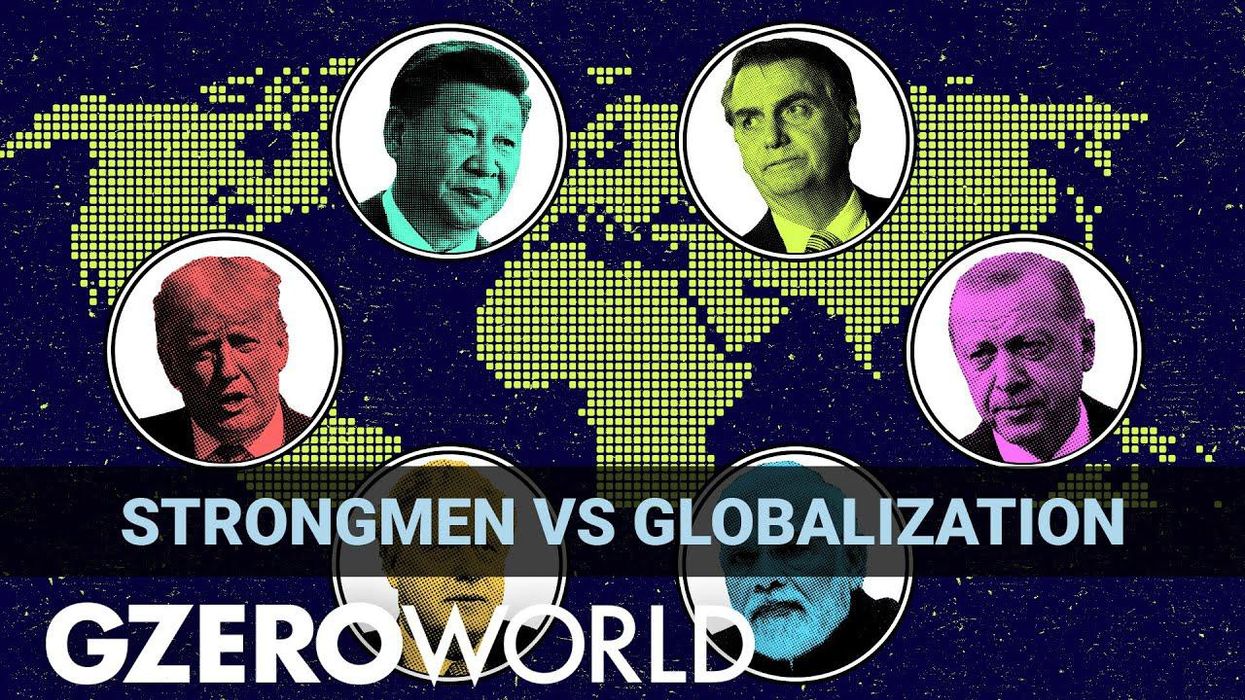

How to consolidate power by creating an enemy

As things become more unstable in the world with inflation and rising food prices, and commodity prices, there is going to be more and more appetite with strong leadership. Part of the pushback against globalization has been led by autocrats who reject things like free trade and the liberal international order. For them, globalization means losing control. But the world today remains more interconnected than ever. So, do they want less globalization, or rather a version that fits their narrative? On GZERO World, Ian Bremmer speaks to Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, who wrote a book about the rise of the age of the strongmen.

Jun 26, 2022