Analysis

10 elections to watch in 2025

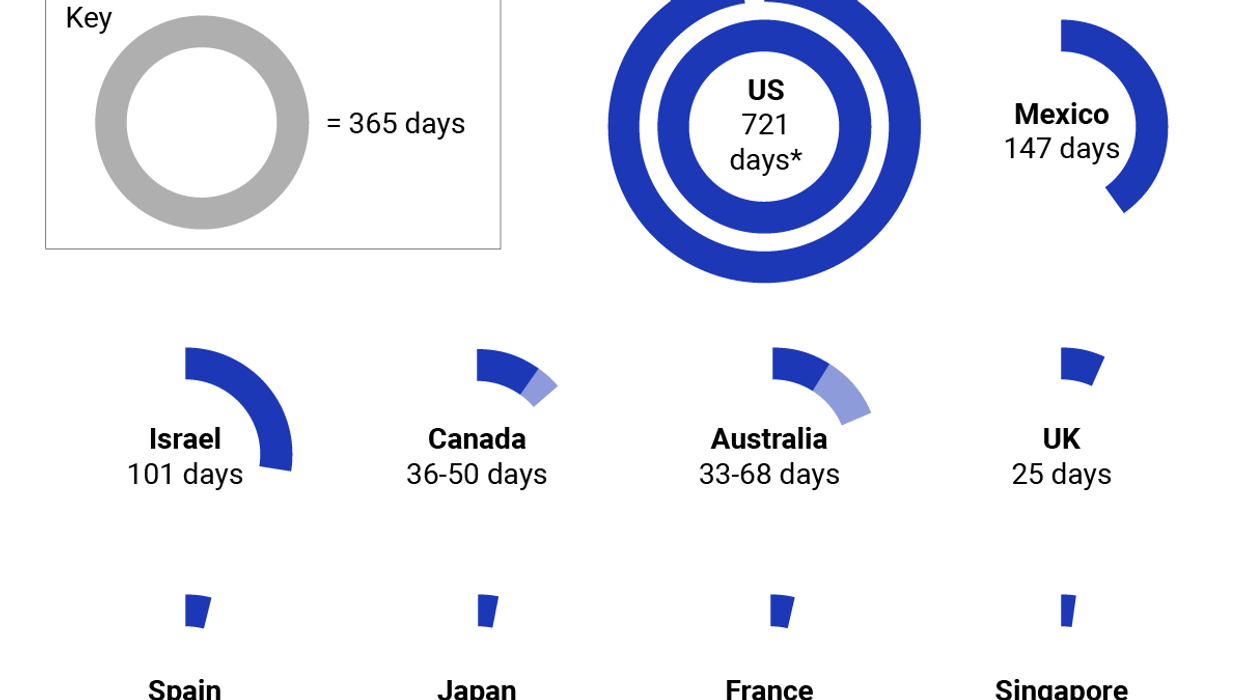

This time last year, we had you buckle up for the world’s most intense year of democracy in action, with more than 65 countries holding elections involving at least 4.2 billion people. As we now know, many of those voters turned against incumbents in 2024 — from the United Kingdom and the United States to Botswana, Japan, and South Korea, just to name a handful. Now, we’re spotlighting the 10 most consequential elections of 2025.

Dec 26, 2024