Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

Putin is becoming more desperate. Could he use a nuclear weapon?

This past week has seen the most dramatic escalation of the war in Ukraine since Russia’s initial invasion on February 24. It comes directly on the back of Russian President Vladimir Putin meeting with his last remaining important friends on the global stage—the leaders of China, India, Kazakhstan, Turkey—all of whom directly pressured him in private and in public to end the war.

What did Putin do in response? He escalated.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily for free and get your daily fix of global politics on top of my weekly email.

Putin called up a minimum 300,000 additional conscripts in a mobilization that he’d been avoiding for months because he knew how unpopular it would be at home.

He announced the formal annexation of four Ukrainian regions—Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson—containing some 7 million people and comprising about 15% of Ukraine’s territory, and took their future status off the negotiating table.

He warned that any military incursions or strikes into these illegally annexed regions would be considered attacks on the Russian homeland and hinted that they would be met with potentially nuclear retaliation, even though Russia didn’t completely control these regions at the time of annexation and there are still active hostilities going on there.

It’s likely he ordered the sabotage of the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 gas pipelines to Europe last week—something the Kremlin denies responsibility for but NATO members are convinced (albeit with only circumstantial evidence to date) the Russians were behind.

Putin addresses a rally at Red Square marking the annexation of Ukrainian territory on September 30.Alexander Nemenov/AFP via Getty Images

Putin addresses a rally at Red Square marking the annexation of Ukrainian territory on September 30.Alexander Nemenov/AFP via Getty Images

Yet these escalatory actions have neither meaningfully improved Russia’s chances on the battlefield, made a dent in Ukraine’s resolve to win the war, nor weakened the West’s support for Kyiv.

In fact, over the last week Ukrainian forces have made significant advances in both eastern and southern Ukraine, pushing Russian troops out of strategic cities in Luhansk, Donetsk, and Kherson regions—three of the four illegally annexed Ukrainian territories. These losses add to the more than 2,000 square miles that Ukraine had recaptured in the Kharkiv region in mid-September, even forcing the Kremlin to admit that the self-declared borders of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions—and, therefore, the claimed borders of Russia itself—have yet to be determined.

Russia’s humiliating battlefield setbacks have prompted rare public criticism from even Putin’s closest cronies and confidants. The shambolic mobilization effort, meanwhile, has been met with nationwide protests and stinging rebukes by even Russian state media. Between 200,000 and 700,000 Russians have fled the country to dodge the draft.

For his part, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky responded to Putin’s escalation by abandoning his past offer of neutrality, signing a request to NATO for fast-track admission to the alliance (which he won’t get but is nonetheless symbolic), and declaring negotiations with Putin an “impossibility.”

The United States and the United Kingdom have already issued new sanctions, and European Union leaders will unanimously agree on an eighth round of sanctions as soon as this Friday, likely including a price cap on imports of Russian oil. The U.S. has also announced a new $625 million arms package including the provision of 4 more HIMARS rocket launchers, on top of the $1.1 billion in security aid and 18 HIMARS announced last week.

In the coming weeks, Ukraine is poised to make additional battlefield gains, especially in the strategic Kherson region. How will Putin respond to further losses of “Russian” territory now that he has publicly committed to defending it by any means necessary?

His troops are incapable of turning the military tide, no matter how much cannon fodder he continues to throw into the meat grinder. He has made negotiations with the Ukrainians a non-starter. And he doesn’t seem prepared to simply take the loss and move on.

Ukrainian soldiers raise the national flag near Lyman, Donetsk region on October 4.(Anatolii Stepanov/AFP via Getty Images)

Ukrainian soldiers raise the national flag near Lyman, Donetsk region on October 4.(Anatolii Stepanov/AFP via Getty Images)

But what other options does he have?

He can and almost surely will cut off all the remaining gas to Europe, in the hopes that the economic and political pain of a tough winter will create divisions and undermine support for Ukraine. But that’s not going to work: the Europeans (and, indeed, all of the allies) have held together incredibly tightly in response to previous Russian escalations, and they are now fairly well-prepared to survive this winter without Russian gas while avoiding severe rationing.

Similarly, he could lash out against Ukraine’s Western supporters by launching asymmetric attacks on NATO members (e.g., cyberattacks, drone or missile strikes on military depots or supply lines). Indeed, Putin’s September 30 speech and Russian state media have been laying the ground for this type of escalation, framing the conflict not as Russia vs. Ukraine but as Russia vs. the collective West. But Putin knows that an attack on NATO would automatically expand the war and trigger direct U.S. military intervention, no doubt precipitating Russia’s total defeat.

That’s why we have to take the nuclear threat seriously: Putin is increasingly boxed in, with no good military, diplomatic, or economic options to turn the tables. He’s losing badly on every front, and in seven short months Russia has gone from China’s most important partner on the global stage to a bigger Iran—a global pariah. Is it possible Putin views nukes, the ultimate game-changer, as the only move he has left?

The White House certainly believes this is a real possibility, and they have explicitly warned Putin that the U.S. would respond to nuclear use by directly attacking Russian troops and military assets on the ground in Ukraine. That would of course turn the current cold/proxy war between Russia and NATO into a full-fledged hot war between nuclear-armed powers.

Everything possible has to be done to avoid that. Unfortunately, while the United States and its allies have proven to be very effective at punishing the Russians and supporting the Ukrainians, they have been incapable of deterring Putin’s behavior. Despite all the actions taken by the West in the last 7 months, he has continued to escalate. It is now clear that at the end of the day, the decision to deploy nukes is up to Putin, and there’s little anyone can do to change that.

I still think it’s very unlikely that the Russians would actually use nuclear weapons on the battlefield. But it’s much more likely now than it was a couple of months ago, and the more desperate Putin gets, the more plausible this scenario becomes. The war is becoming more dangerous.

🔔 Don't forget to subscribe to GZERO Daily and get the world's best global politics newsletter every day PLUS a weekly special edition from yours truly. Did I mention it's free?

Revisiting Holodomor, the controversial 1932-33 Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

Revisiting Holodomor, the controversial 1932-33 Soviet genocide against Ukrainians

This November marked the 88th commemoration of the 1932-33 Ukrainian Holodomor, the famine caused by Joseph Stalin’s forced collectivization of agriculture that killed more than 3 million Ukrainians out of between 6 and 11 million total victims across the Soviet Union.

The narrative around the Holodomor has been the subject of controversy for decades. While today historians largely agree that the famine was the result of Soviet policy (rather than a tragic natural disaster) and that ethnic Ukrainians were disproportionately affected by it (they were 30-50% of the victims but only 21% of the Soviet population), this wasn’t always the case.

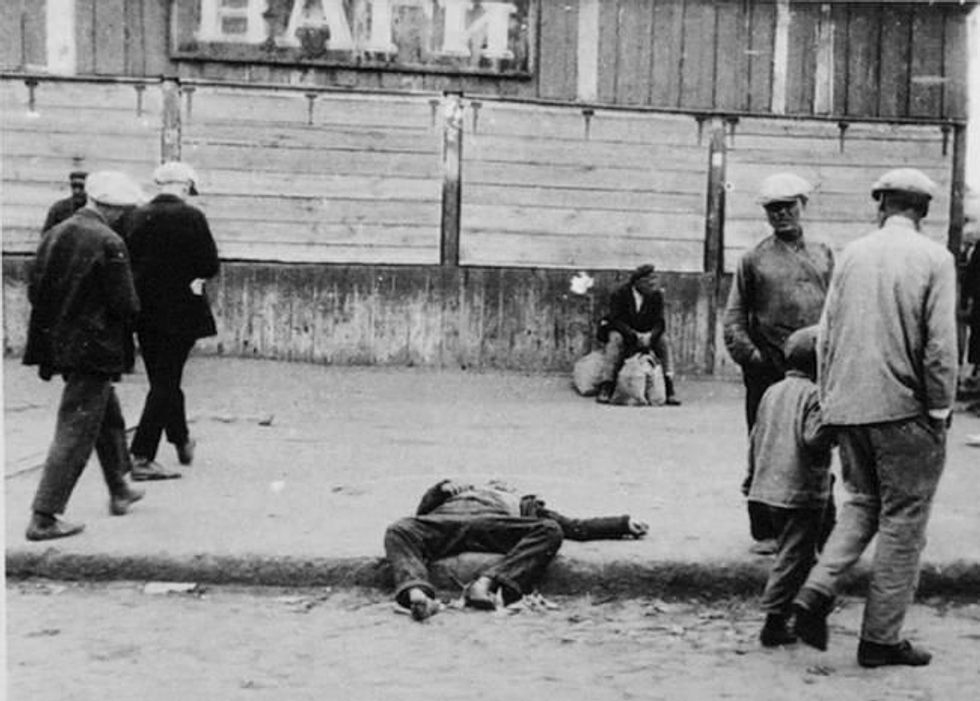

"The sympathy shrinks," the photographer notes in his original caption. Kharkov, Ukraine. 1933.(Wikimedia Commons)

"The sympathy shrinks," the photographer notes in his original caption. Kharkov, Ukraine. 1933.(Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, it wasn’t until my PhD advisor and dear mentor Robert Conquest published his 1987 book, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, that these facts gained wide acceptance.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

Conquest’s Harvest of Sorrow was the first book to authoritatively document the Holodomor. It was also the first to credibly claim that the famine was deliberately imposed on the Ukrainian peasantry by the Soviet state for ethnic reasons. The book had such an impact that many Ukrainians first learned about the deadly famine from translated excerpts broadcasted on Radio Liberty. (Incidentally, Bob was the person that got me interested in Ukraine, to the point where I moved to Kiev briefly in 1992 and wrote my dissertation on the politics of ethnicity in Ukraine and Russia.)

But not everyone was convinced. Several scholars rejected Conquest’s conclusion that the famine was systematically biased against Ukrainians and therefore that it was genocide. Instead, they noted the famine killed many non-Ukrainians, both in Ukraine and elsewhere in the Soviet Union. While Stalin’s agricultural policies did kill Ukrainians at a higher rate than other ethnic groups, they claimed this was due to factors outside the government’s control, such as bad weather and pre-famine policies and features (such as Ukrainians being disproportionately represented in agriculture or living on more productive land) rather than deliberate state policy.

Soviet guards take crops from Ukrainian farmers in Odessa, 1932.(Wikimedia Commons)

Soviet guards take crops from Ukrainian farmers in Odessa, 1932.(Wikimedia Commons)

To this day, outside of academia there is no universal consensus about whether the 1932-33 famine was a crime against humanity committed in the Soviet Union’s pursuit of its economic and political objectives or an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people.

The Ukrainian government officially recognized the Holodomor as a genocide in 2006, but only 15 other nations (including Australia, Canada, Mexico, and the Baltics) have followed suit. Russia categorically rejects the label for obvious reasons. Opposition from the Kremlin explains why the UN General Assembly and the European Union, which depends heavily on Moscow for energy and regional stability, recognize Holodomor as a crime against humanity but not a genocide. The potential backlash from Putin also explains why no US president has ratified the genocide declaration issued by the US Congress.

Enter a new study published last July by economists Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, titled “The Political-Economic Causes of the Soviet Great Famine, 1932–33”. From the abstract (emphasis mine):

This study constructs a large new dataset to investigate whether state policy led to ethnic Ukrainians experiencing higher mortality during the 1932–33 Soviet Great Famine. All else equal, famine (excess) mortality rates were positively associated with ethnic Ukrainian population share across provinces, as well as across districts within provinces. Ukrainian ethnicity, rather than the administrative boundaries of the Ukrainian republic, mattered for famine mortality. These and many additional results provide strong evidence that higher Ukrainian famine mortality was an outcome of policy, and suggestive evidence on the political-economic drivers of repression. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that bias against Ukrainians explains up to 77% of famine deaths in the three republics of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus and up to 92% in Ukraine.

In short, the paper offers novel, rigorous, and compelling evidence that the Holodomor was indeed premeditated and intentional genocide against ethnic Ukrainians, rather than the unintended consequence of bad but ethnically neutral collectivization policies.

A woman walks by two starving peasants dying on the streets of Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1932 (Wikimedia Commons)

A woman walks by two starving peasants dying on the streets of Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1932 (Wikimedia Commons)

The authors find that higher famine mortality for ethnic Ukrainians was not due to “differences in agricultural production, weather or urbanization” or to Ukrainians’ socio-cultural and institutional differences relative to other Soviet ethnic groups. Moreover, ethnic Ukrainians’ excess mortality was just as high in Russia as in territorial Ukraine, meaning that “Soviet policies which led to the famine targeted ethnic Ukrainians rather than Ukraine.” Combined, these findings suggest that ethnic Ukrainians were systematically targeted. This ethnic bias explains 9 out of 10 famine deaths in Ukraine and close to 8 out of 10 deaths throughout the Soviet Union.

But why did the Soviet state target ethnic Ukrainians? Did Stalin want to exterminate them simply because of who they were, or was there a more instrumental reason? The authors test a bunch of hypotheses and rule out crude ethnic hatred as the main driver, finding that “Ukrainian areas do not suffer higher famine mortality if they are not agriculturally productive.” Instead, they conclude that the targeting of Ukrainians stemmed from Stalin’s need to control agricultural production. Famine mortality was driven by collectivization and grain procurement, the regime’s centrally planned agricultural policies, which were “more intensively enforced in regions with larger Ukrainian population shares”:

Since Ukrainians were the largest ethnic group in productive areas, had a stronger ethnic identity than other groups and were in sharp conflict with the Bolsheviks in 1917 and during the Civil war, the regime repressed Ukrainians more than other groups living in productive regions to overcome potentially stronger resistance[…] Amongst the subversive peasants according to Stalin’s view, ethnic Ukrainians were the most problematic […] Thus, it is likely that the Soviets systematically repressed Ukrainians during the famine to strengthen their control over agriculture.

These findings vindicate Conquest’s conclusions: Holodomor was a genocide perpetrated along ethnic lines, the scars of which continue to live on.

Ukrainian activists protest outside the Russian embassy in Kiev in 2020, during a protest called "You killed us then and continue to kill us now".(Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images)

Ukrainian activists protest outside the Russian embassy in Kiev in 2020, during a protest called "You killed us then and continue to kill us now".(Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images)

Even if the Holodomor itself wasn’t primarily motivated by Russian hatred of Ukrainians, the famine inflamed ethnic tensions that have sown discord between the two nations ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Remember this the next time you read about the West’s worries that Russia might invade Ukraine… again.

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.

Welcome to the GZERO

Welcome to the GZERO

Hi, I’m Ian Bremmer, and I want to help us all become a little less crazy. Starting now.

I think, talk, and write about global politics for a living. That's too important a subject to be left to “schools of thought,” which is why I left academia to go into business—the business of geopolitics. And because so many people know they don’t really understand this subject—and know they need to—I and 200 of the smartest people I know have built the world’s largest political science company, Eurasia Group.

Yet, I rarely get to really engage, argue, and laugh with those who follow me on TV, in print, or in social media. That’s what this page is for—and why I’m glad you’re here.

Want to understand the world a little better? Subscribe to GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer for free and get new posts delivered to your inbox every week.

You might be wondering about the title, GZERO World. Here’s the idea: We don’t live in a world run by the leaders of the “Group of 7” (G-7) countries, or the G20, or any secret coalition of cool heads, deep pockets, and great powers. This is the GZERO, a moment in history where nobody is driving this bus. “Global leadership” today is full of contradictions: the United States is the world’s superpower—but also the most politically divided and dysfunctional of the rich democracies. China is #2—but also the most unified and stable of authoritarian regimes. America First? It’s more like Every Nation for Itself.

That’s why I named my media company GZERO Media and my weekly public television show and podcast GZERO World.

On the show, I talk to newsmakers about the events and ideas driving headlines. But there’s only so much we can cover in 30 minutes a week, so in this newsletter, we’ll continue those conversation and go deeper.

World news today is stressful. I’m writing this page to separate fact from fiction, signal from noise, and the trivial from the essential. I think that’s the secret to making us all 10% less crazy. I can’t do 50%. That’s water weight. You’ll go back to your regular news diet and gain it right back. But with a little focus and a little time, 10% is doable. So let’s do it!

A warning—If you only “like” ideas you already agree with, this page is probably not for you.

I’m going to make my case on issues like America’s role in the world, China’s rise, Europe’s future, Russia’s plans, Latin America’s evolution, Africa’s promise, pandemic fallout, climate change, dangerous new technologies, and all things GZERO. I invite you to think with me, argue with me, and tell me about it. You read my posts, and I’ll read your comments, because I care very much what YOU think.

So, thanks for stopping by, and here we go!

🔔 And if you haven't already, don't forget to subscribe to my free newsletter, GZERO Daily by Ian Bremmer, to get new posts delivered to your inbox.