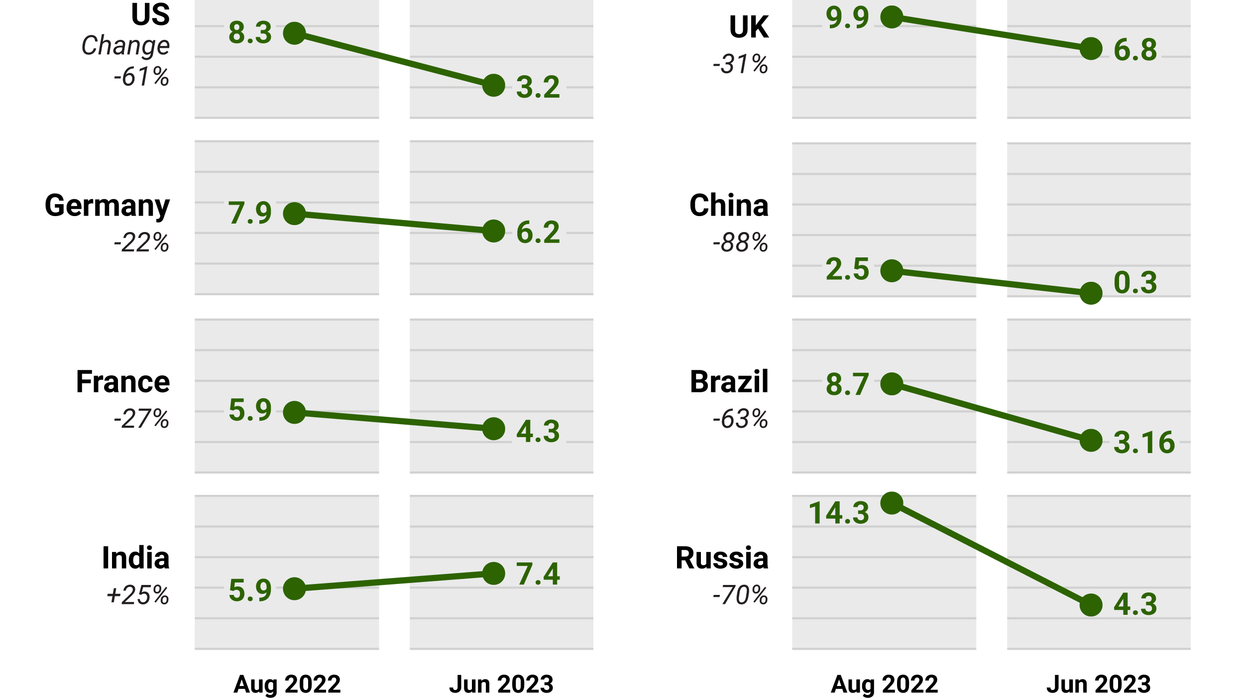

Graphic Truth

The Graphic Truth: Summer inflation – then and now

The summer of 2022 was, broadly speaking, the summer of inflation. An energy crunch caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine, coupled with increased post-COVID demand and supply chain kinks sent prices through the roof. Elevated oil and gas, in particular, set records around the globe.

Aug 17, 2023