GZERO World Clips

Why Pakistan sees China as a "force for stability"

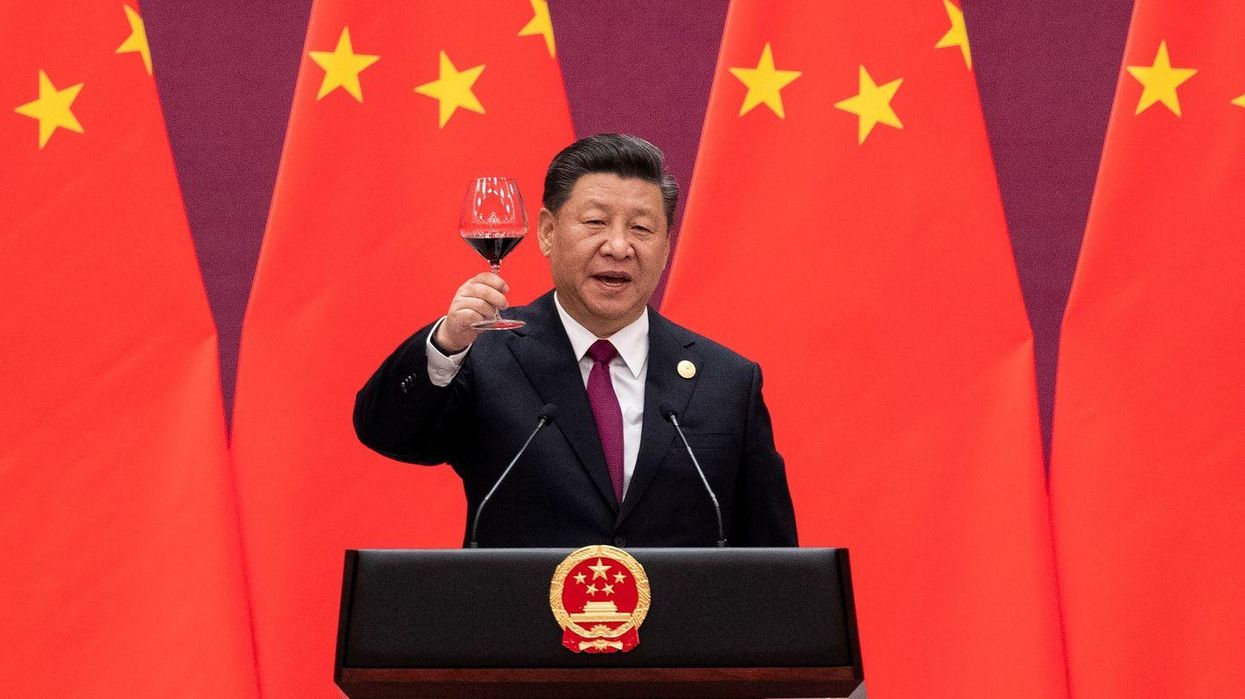

Pakistan and China have deep strategic and economic ties that go back decades. On GZERO World with Ian Bremmer, Former Pakistani Foreign Minister Hina Khar explains why Pakistan sees China as a “force of stability” in Southeast Asia.

Aug 18, 2025