Climate

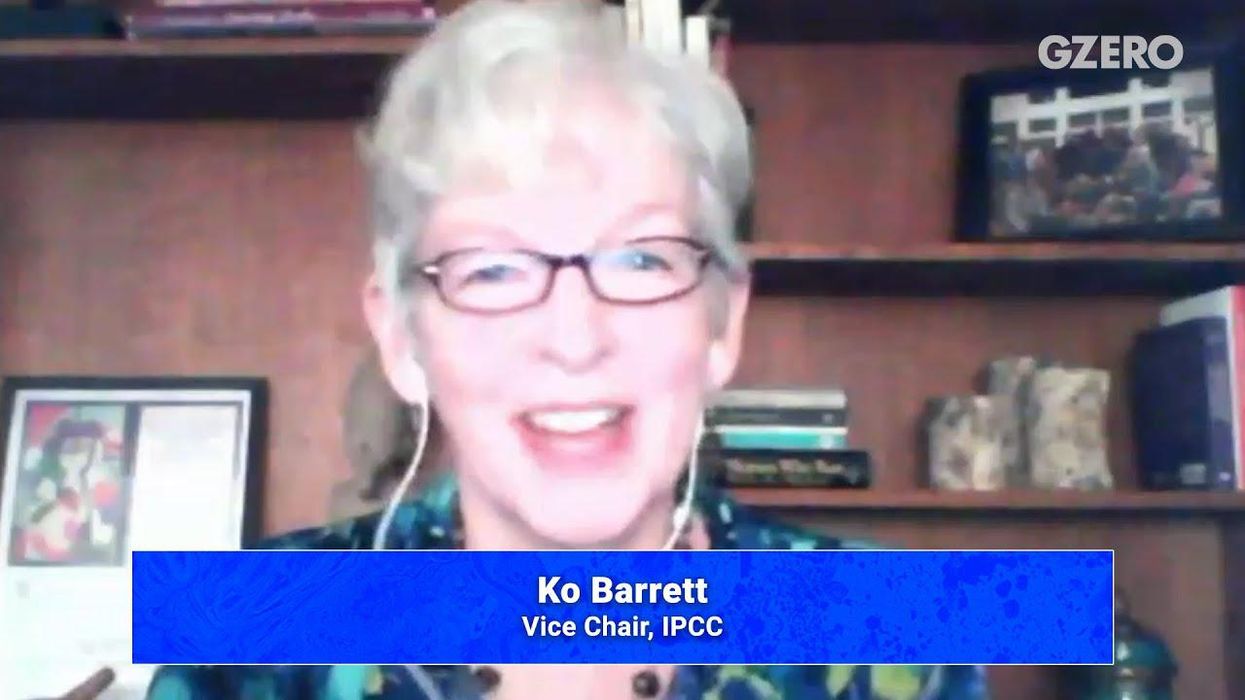

Asia will lose land as the planet warms, says IPCC's Ko Barrett

Last August, a landmark IPCC report underscored the urgency of the climate crisis — with big implications for Asia, the region most at risk. Ko Barret, vice president at the IPCC, says Asia should especially watch out for a combination of sea level rise above the global average and a lot more rain than usual that'll together result in shorelines receding along the Mekong delta. Barrett spoke during the first of a two-part Sustainability Leaders Summit livestream conversation sponsored by Suntory.

Oct 31, 2021