Middle East

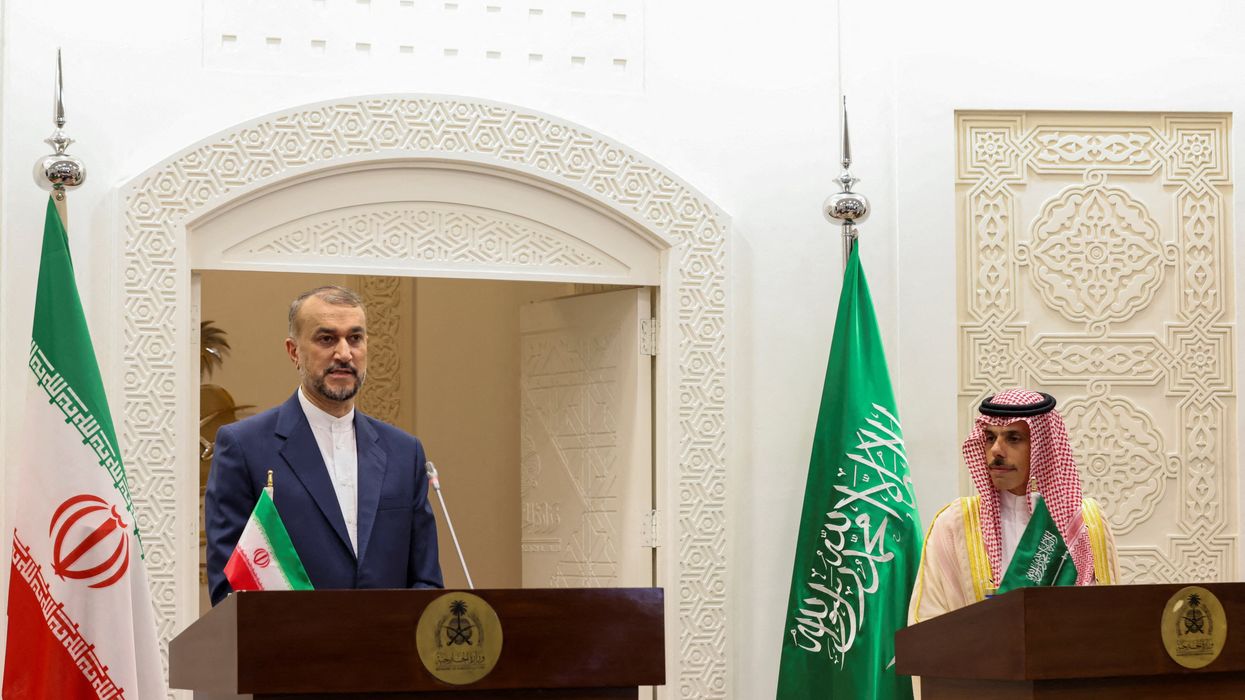

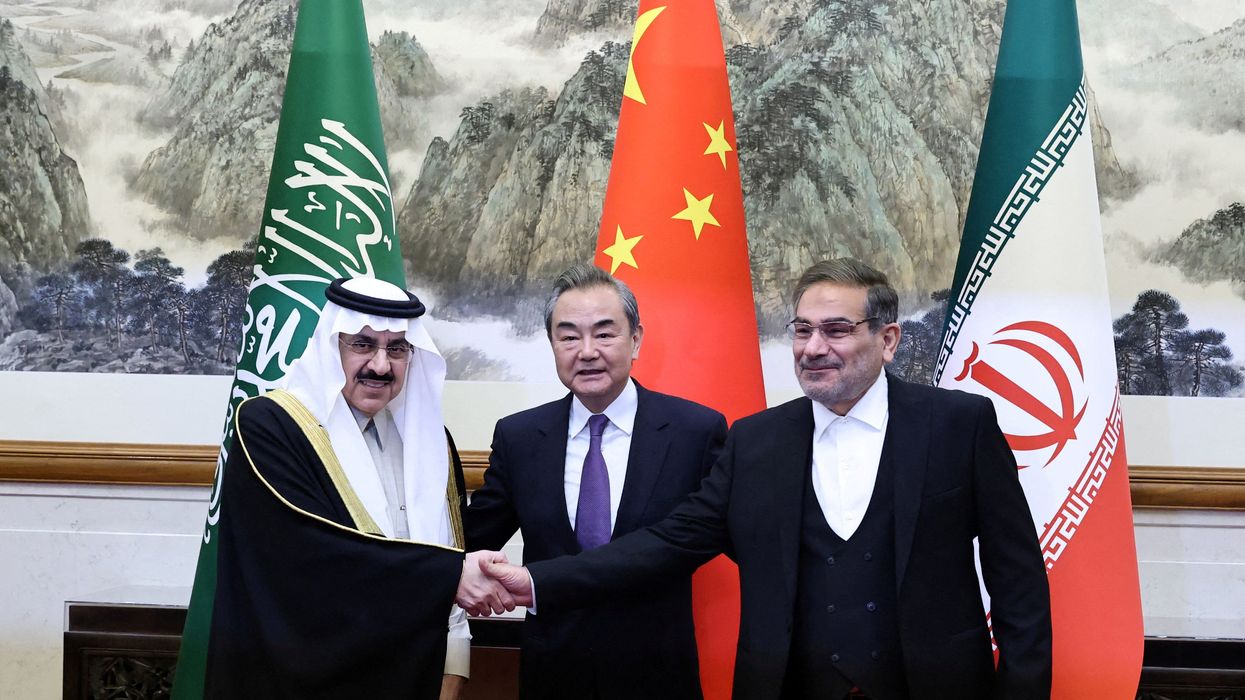

As diplomatic thaw continues, Saudi Arabia and Iran exchange ambassadors

The rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran continued this week when the two Middle East powers exchanged ambassadors for the first time in seven years. This comes after they reopened embassies in each other's capitals over the past few months as part of a groundbreaking detente.

Sep 06, 2023