News

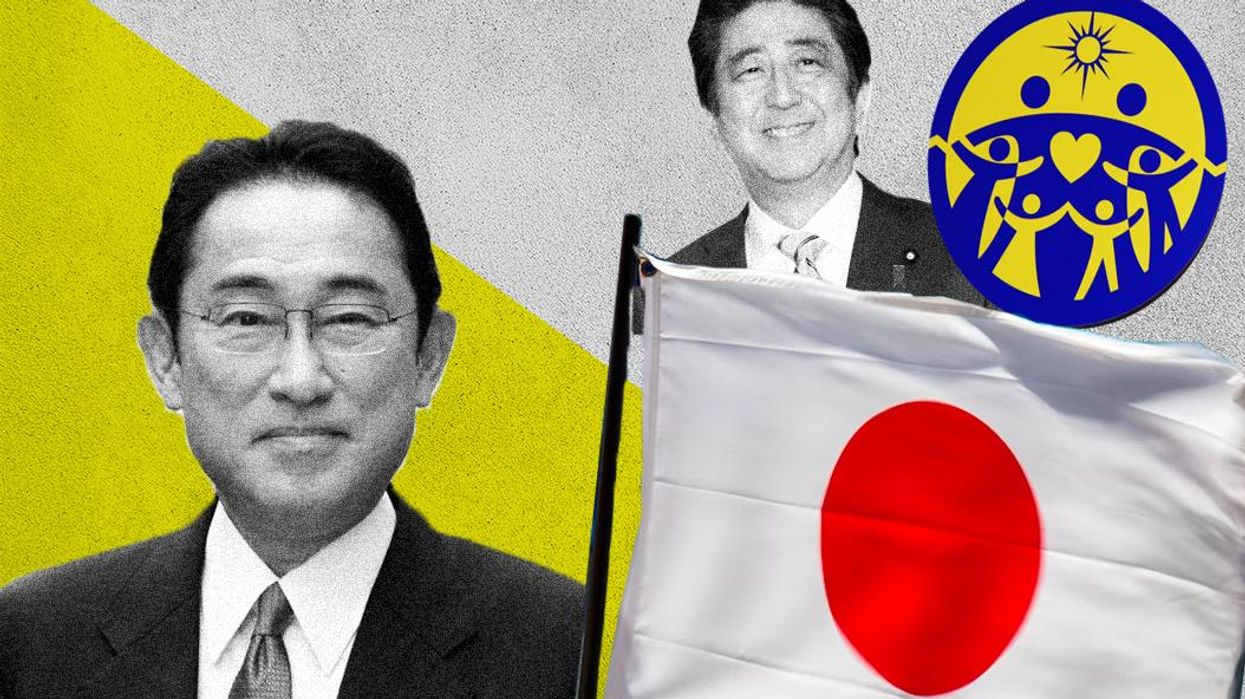

Why Japan’s political Moonies have staying power

It'll be hard for Japan's ruling party to completely cut ties with the Unification Church — no matter how unpopular the Moonies have become in the wake of former PM Shinzo Abe's assassination.

Aug 24, 2022