News

The road ahead for Macron is only getting rougher

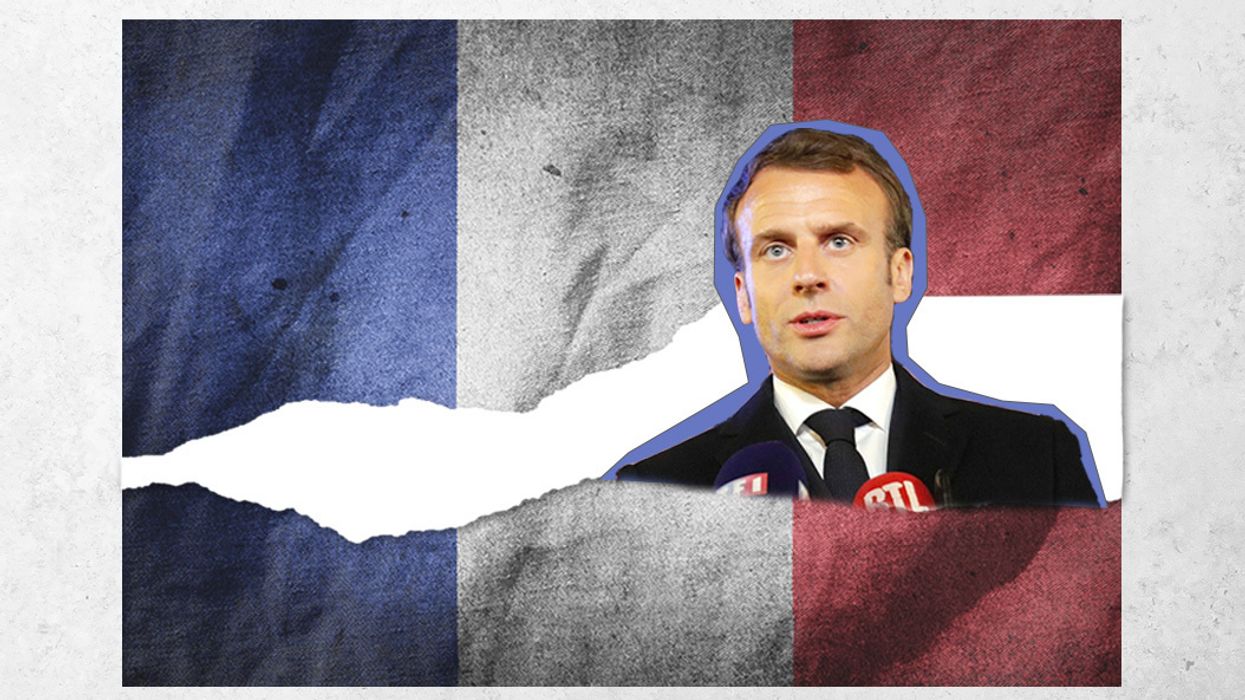

Several months ago, we considered the "rough road ahead" for French President Emmanuel Macron after his political party, La République En Marche, took a thrashing in local elections. Since then, things have only gotten tougher for the man once hailed as France's centrist savior. What political challenges are plaguing Macron and what comes next?

Nov 18, 2020