What We're Watching

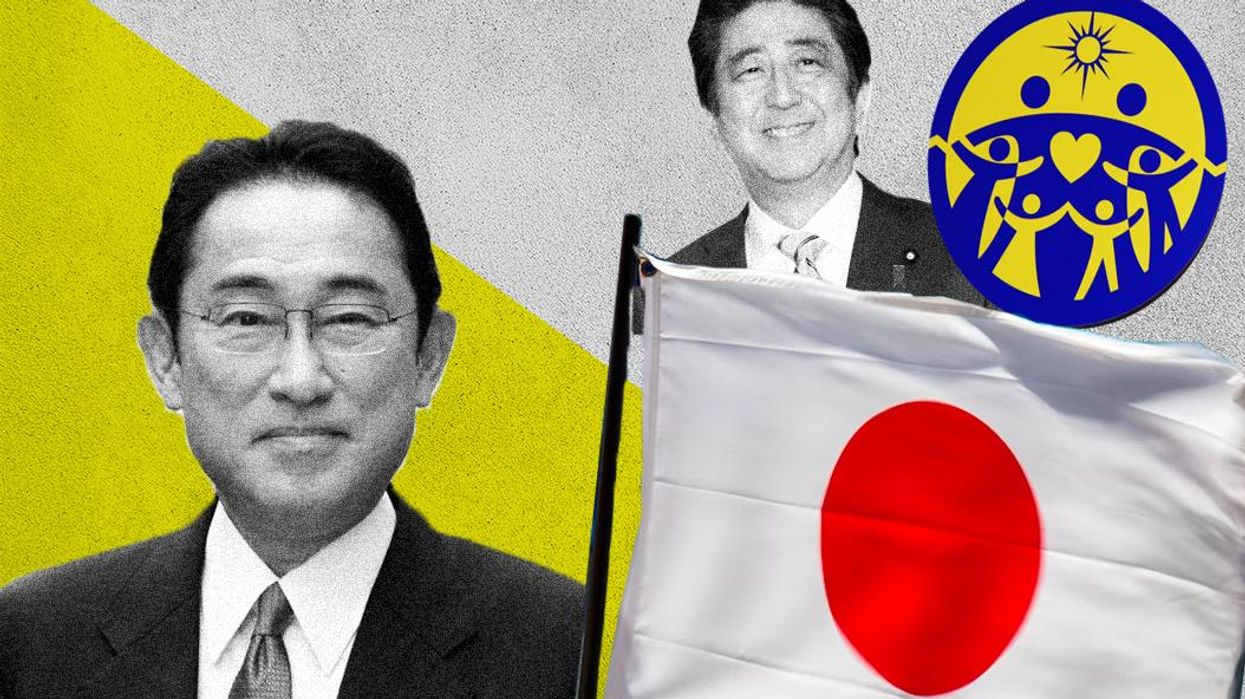

Japan bans Moonies

On Tuesday, a Tokyo court revoked the legal status of the Unification Church in Japan, ordering the sect known as the Moonies to disband following a government problem spurred by the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2022.

Mar 25, 2025