popular

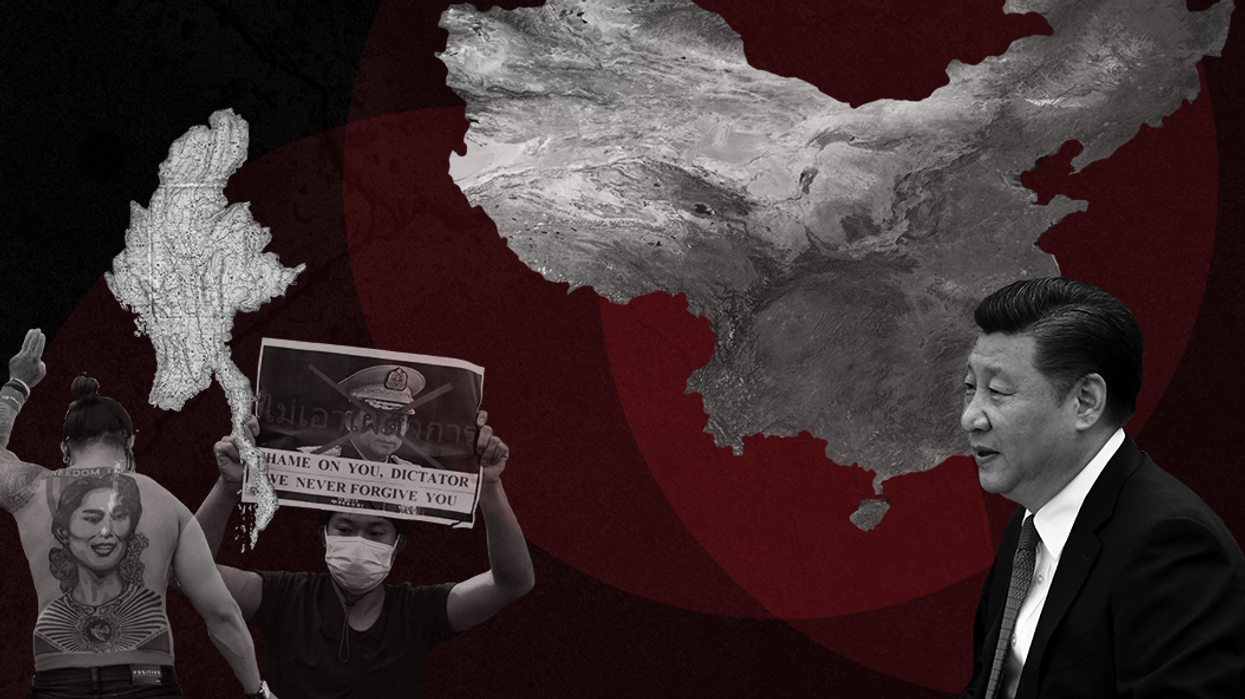

With its interests in flames, what will China do in Myanmar?

As Myanmar's political crisis deepens, protesters are taking aim at Chinese business interests. Growing anti-China sentiment is big test for Beijing, which faces a tough choice on how to respond.

Mar 15, 2021