News

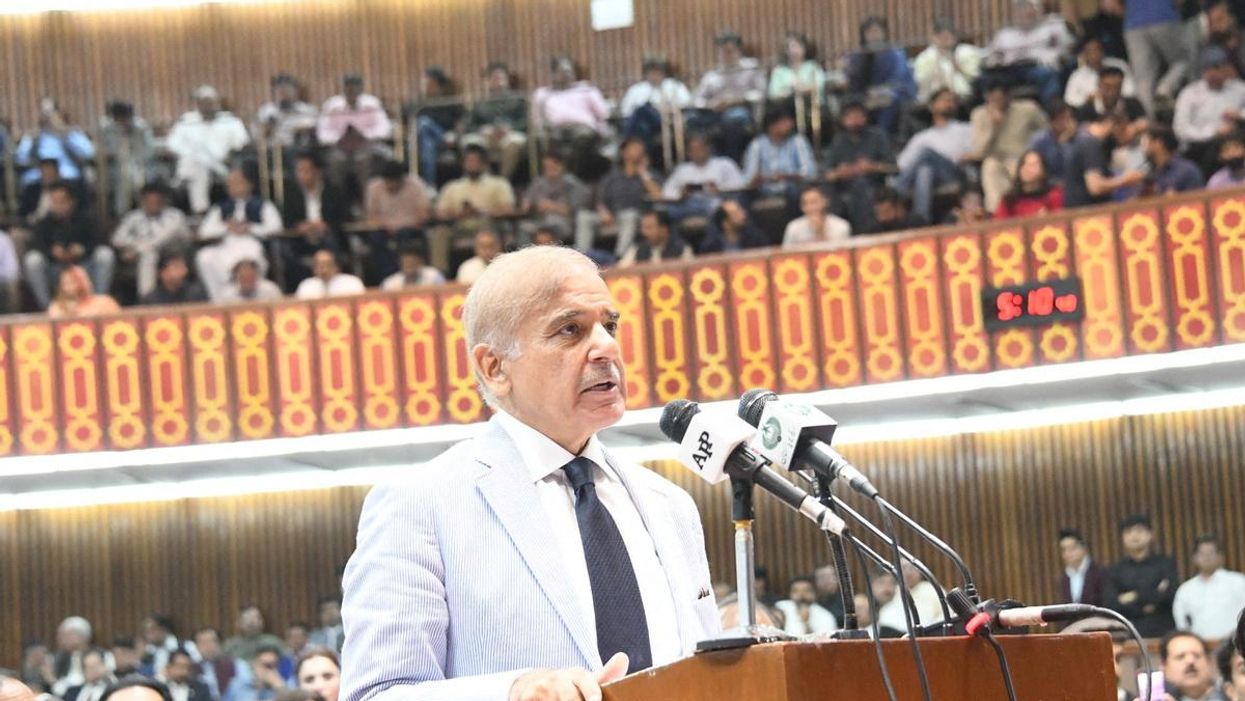

Can Sharif succeed despite Khan’s fiery exit?

As Pakistani PM Imran Khan saw his tenure draw to a close in recent weeks, the former cricket star began pointing fingers at the West, blaming the push for regime change in Pakistan on a US conspiracy. While it didn’t help him stay in the red zone, it did mean Khan was already plotting his return. Following Khan’s ouster on Saturday, the parliament elected Shehbaz Sharif on Monday. This prompted the resignation of much of Khan’s Tehreek-e-Insaf Party from the National Assembly, setting the stage for by-elections to fill those seats.

Apr 12, 2022