Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

US-China relations can be improved under Biden, but geopolitical rivalry & human rights can't be ignored

In their latest op-ed for Project Syndicate, Javier Solana and Eugenio Bregolat stress the importance of the US and China not becoming staunch enemies - but the piece also avoids some uncomfortable truths about the US-China competition. Ian Bremmer, along with Eurasia Group analysts Michael Hirson and Jeffrey Wright, grabbed The Red Pen to clarify a few points re the US-China relationship.

Today we are taking our Red Pen to an op-ed from Project Syndicate, always gets distributed globally, written by two veteran Spanish diplomats, Javier Solana and Eugenio Bregolat. Among their many accolades, Solana served as Secretary-General of NATO and Bregolat was Spain's ambassador to China. So, not too shabby. And full disclosure, Javier is actually a dear and longstanding friend. So, I'm biased. But that doesn't stop The Red Pen.

Their article is titled "Biden Can Pass His China Test," and it focuses on what will be the most important foreign policy challenge that Biden will face as president, America's relationship with China, the second most powerful country in the world. The authors argue that under Trump that relationship deteriorated significantly, all-out battles over technology, trade, human rights, and even a giant global blame game over the coronavirus pandemic.

The piece makes solid points about the importance of the two nations not becoming staunch enemies. Their cooperation on everything from climate change to nuclear proliferation to cyber norms no doubt will be critical in the coming years. And we agree that the Trump administration's approach, particularly its rhetoric, requires recalibration in the Biden presidency. But the piece also avoids some uncomfortable truths about how difficult the road ahead is going to be in US/China diplomacy.

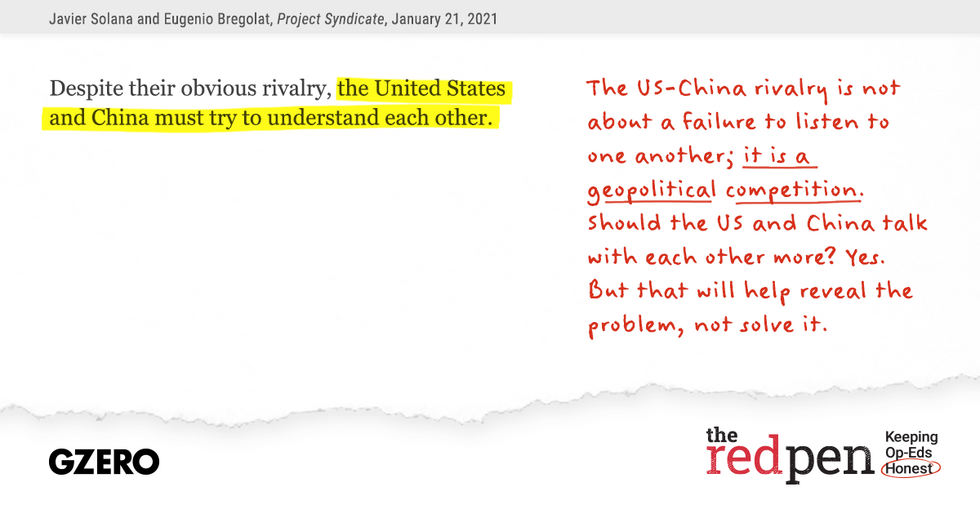

So first, Solana and Bregolat argue that "despite their obvious rivalry, the United States and China must try to understand each other" as they seek peaceful coexistence.

Now, let's be real: The rivalry between these two nations isn't about a failure to listen to one another. It's a geopolitical competition, particularly in and over Asia (though it's increasingly global) to dominate commercial sectors like technology and also increasingly zero-sum direct security concerns. Talking helps, absolutely, but won't change that underlying reality.

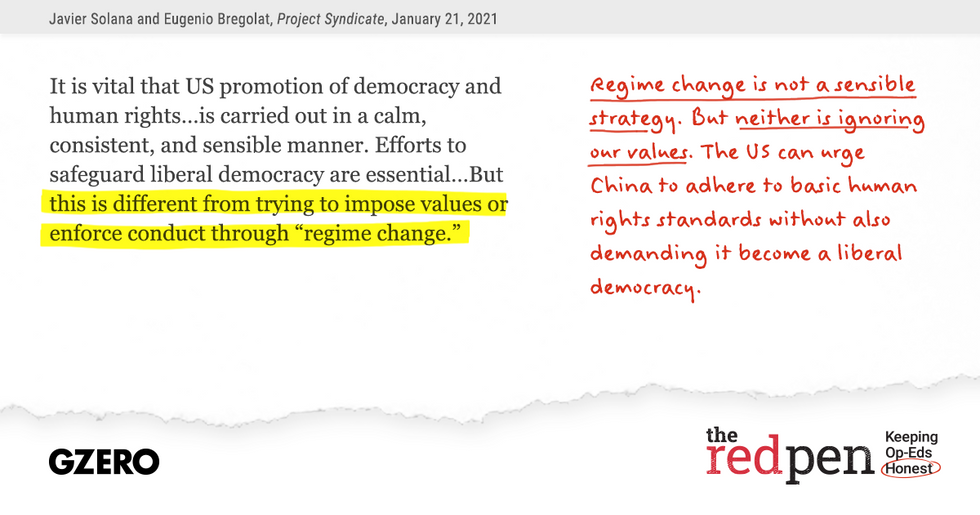

Next, the authors urge Biden to promote democracy and human rights in a "calm, consistent, and sensible manner" and avoid "trying to impose values."

Never mind the fact that actually, Trump himself did virtually none of that, but calling for regime change in China is clearly not a sensible strategy. But neither is ignoring our values or Western values. And the United States can urge China to adhere to basic human rights standards without also demanding it become a liberal democracy. Treatment of Uighurs is at the top of the list. As is breaking the "one country, two systems" promise in Hong Kong. These things can't be swept under the rug, by the Americans or our allies across the pond, for that matter.

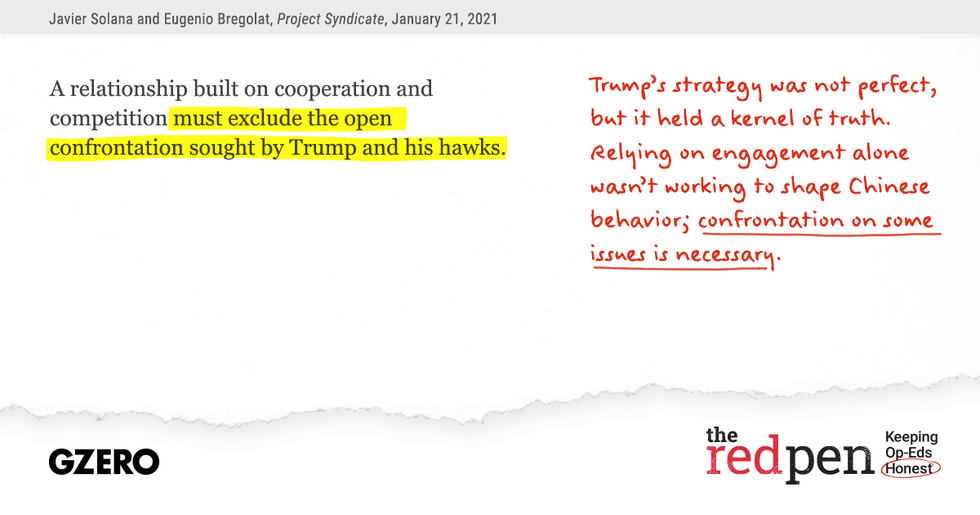

Solana and Bregolat also write that "a relationship built on cooperation and competition must exclude the open confrontation sought by Trump and his hawks."

And here, I want to say that Trump's strategy, while in many ways' imperfect, actually also held some truth. Relying on engagement alone, which is what we mostly saw under the old Obama administration, wasn't working to shape Chinese behavior. The smartest people on Team Trump and Team Biden both recognize that confrontation on some issues is necessary. Indeed, in overall policy orientation, Team Biden and Team Trump probably closer and see eye-to-eye on China than any other foreign policy issue.

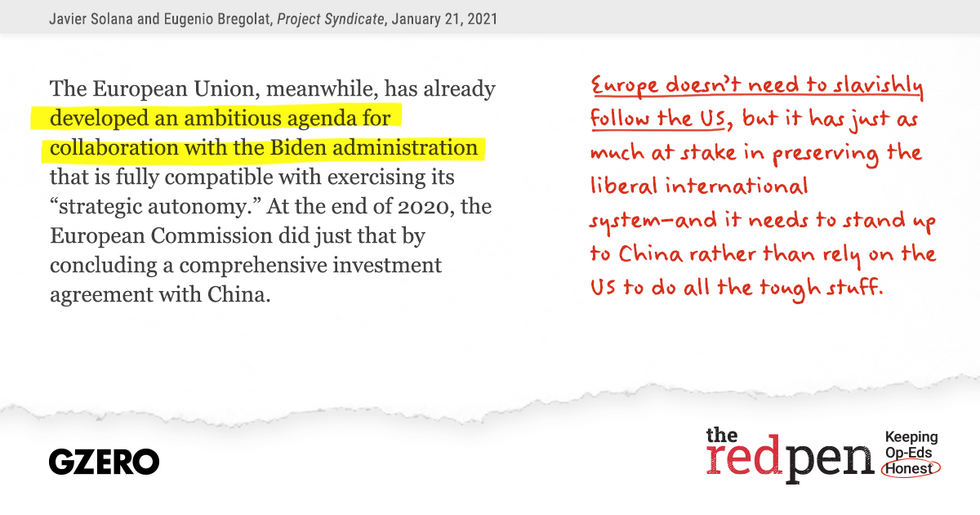

Finally, Solana and Bregolat say that the EU is exercising "strategic autonomy" by developing "an ambitious agenda for collaboration" with Biden while also "concluding a comprehensive investment agreement with China."

Yep, Europe is a significant part of the equation here. But just as the EU doesn't need to slavishly follow the United States, it also shouldn't sign a last-minute deal with China and expect a pat on the back from Washington. Europe has just as much stake in preserving the liberal international system as does the United States, even though that is getting harder and the support for it is eroding.

Well, there you have it, that's your Red Pen for this week. We will have much more to say about the US and China in the coming months, that is for sure. Stay tuned.

The recovery will be a jagged swoosh, not a V-shape

British economist Jim O'Neill says the global economy can bounce back right to where it was before, in a V-shaped recovery. But his argument is based on a lot of "ifs," plus comparisons to the 2008 recession and conditions in China and South Korea that may not truly apply. Ian Bremmer and Eurasia Group's Robert Kahn take issue with O'Neill's op-ed, on this edition of The Red Pen.

Today, we're taking our Red Pen to an article titled "A V-Shaped Recovery Could Still Happen." I'm not buying it. It's published recently by Project Syndicate, authored by British economist named Jim O'Neill. Jim O'Neill is very well known. He was chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management. He's the guy that coined the acronym BRICS, Brazil, Russia, India, China. So, no slouch. But as you know, we don't agree with everything out there. And this is the case. Brought to you by the letter V. We're taking sharp issue with the idea that recovery from all the economic devastation created by the coronavirus pandemic is going to happen quickly. That after the sharp drop that the world has experienced, everything bounces back to where it was before. That's the V. Economists around the world are debating how quickly recovery will happen to be sure. But we're not buying the V. Here's why. W-H-Y.

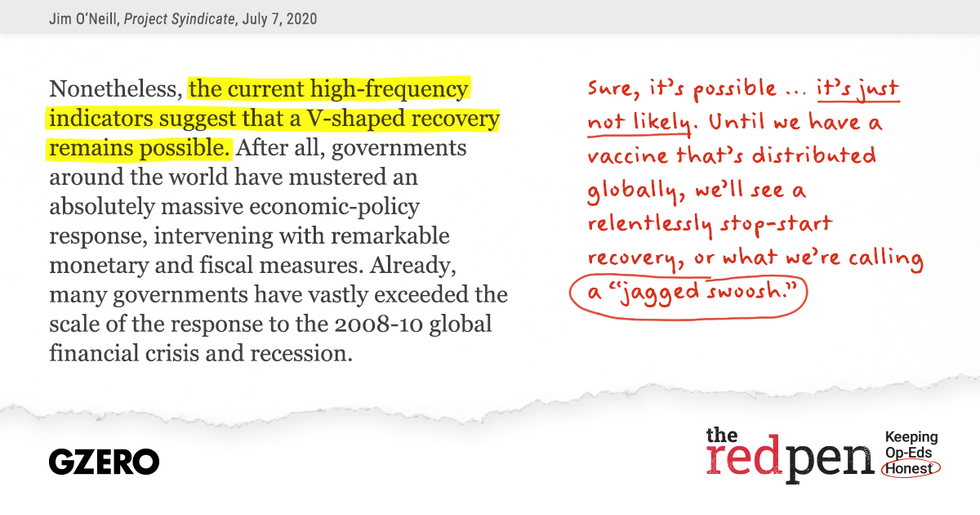

First, among his arguments, O'Neill points to stimulus money pouring in from all corners of the globe. He writes, "After all, governments around the world have mustered an absolutely massive economic response, exceeding the amounts even provided during the 2000, 2008-2010 financial crisis." No question. But this is not the 2008 recession. This moment has brought the entire world's supply chain, massive disruption, debt-distress, unlike anything we've seen in our lifetimes. And with the virus very much still exploding around the world and no vaccine for the moment and none really expected that would work and be distributed globally until at best, mid, late next year, we're likely to see a relentlessly stop and start economy that more resembles what we think is a jagged swoosh, then a V. Sure, we've had a good balance after a very steep decline, but all indications are that the hard part is still to come.

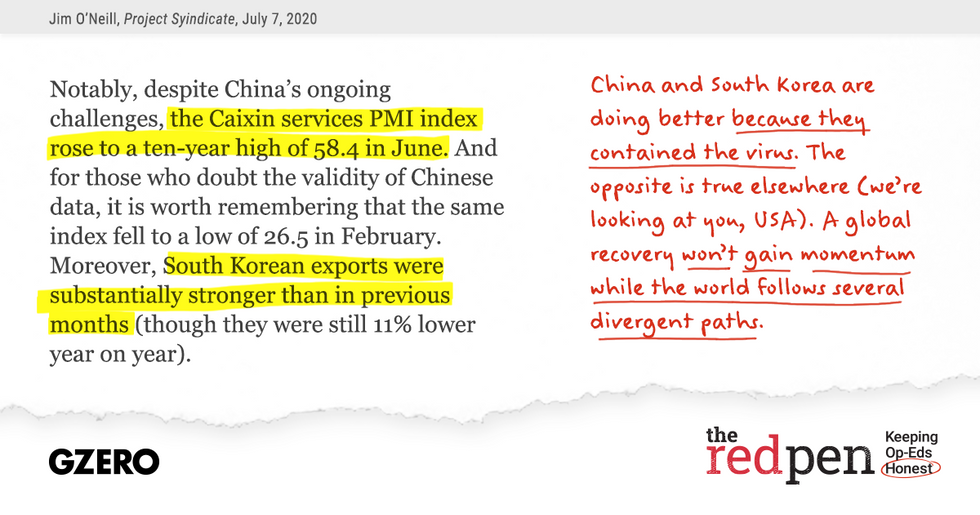

Second, O'Neill writes that improving conditions in China and South Korea bode well for the rest of the world. He writes, "despite China's ongoing challenges, the Caixin services PMI index rose to a 10-year high in June," and he points to increased exports from South Korea, too. Sure, China and South Korea, but they're doing particularly well because they contained the virus. They quarantined. They had contact tracing. They had early testing. That's not true in much of the rest of the world. Certainly not in my own United States, the world's largest economy. Not in Brazil. Not in India. Not in most of the world's emerging markets. A global recovery will not gain momentum while the world is following completely divergent parts.

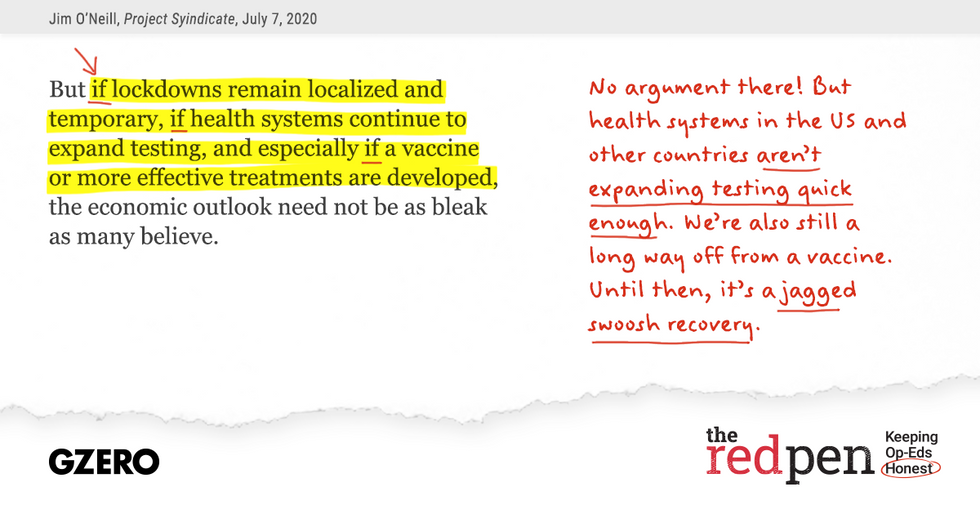

And finally, O'Neill writes, "If lockdowns remain localized and temporary, if health systems continue to expand testing, and especially if a vaccine or more effective treatments are developed, the economic outlook need not be as bleak as many believe." Those are some very big "ifs", my friend. Testing is nowhere close to what it needs to be in the United States and in most of the developing world, aside from China.

Yes, the United States is testing a lot more than it used to, but nowhere close to the explosion of cases that we have right now. We're still looking for effective treatment options, let alone the vaccine that could potentially take years to develop and distribute globally. And if the first vaccines are not seen as effective, a lot of people are going to wait. They're not going to take them immediately. That's even with good education. That's even, never mind, anti-vaxxer sentiment. And it's not paying attention to vaccine nationalism and the fact that the world is not rowing together in developing a vaccine together, which is what you want to respond to a global pandemic.