Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

Hong Kong is a tragedy, not a domino

This week, Ian Bremmer is joined by analyst Michael Hirson to take the Red Pen to an op-ed by New York Times Opinion columnist Bret Stephens.

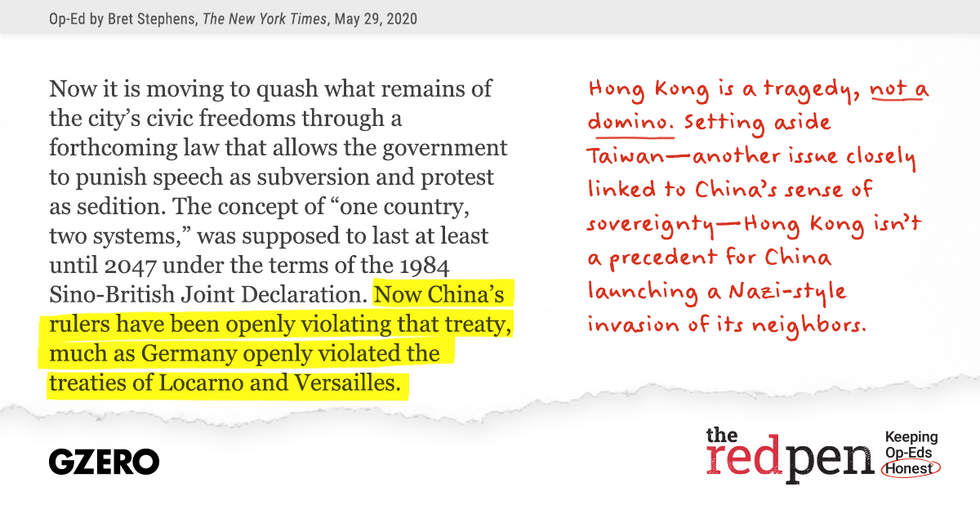

Today, we're marking up a recent op-ed by New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, entitled "China and the Rhineland Moment." And the subheading here is that "America and its allies must not simply accept Beijing's aggression." Basically, Bret is arguing that US-China relations are at a tipping point brought on by China's implementation of a new national security law for Hong Kong. And he compares this to Hitler's occupation of the Rhineland in 1936, describes it as the first domino to fall in Beijing's ambitions.

Now, I mean, no question, the United States and China are at a precarious place in our relationship. The worst US-China relationship that we've seen since the collapse of the Soviet Union, maybe even the start of a Cold War. But to imply that this is the brink of an actual war, as the Rhineland moment was with the Germans, is a bit misguided. Let's take a look at some of his key points.

First, let's start with China's actions mirroring a Nazi Germany's attempt to take over Europe. Stephen writes, "The concept of one country, two systems was supposed to last until 2047 under the terms of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration ..." (The handover in 1997.) "...Now, China's rulers have been openly violating that treaty, much as Germany openly violated the trees of Locarno and Versailles." Hong Kong is definitely a tragedy and it is a breach, but it's not a domino. And setting aside Taiwan, an ally of the United States, that China does indeed intend to take over, it's hard to make the argument that China has imperial ambitions across Asia the way that the Nazis did in Europe. And I mean, leaving aside the immense pushback that we already see across Asia against Chinese efforts to have more influence, the South China Sea for example, Belt and Road for example, the rise of India for example, it's not as if the Chinese - this is not territorial ambitions, this is economic investment and leverage. Again, not leading to a tipping point into war.

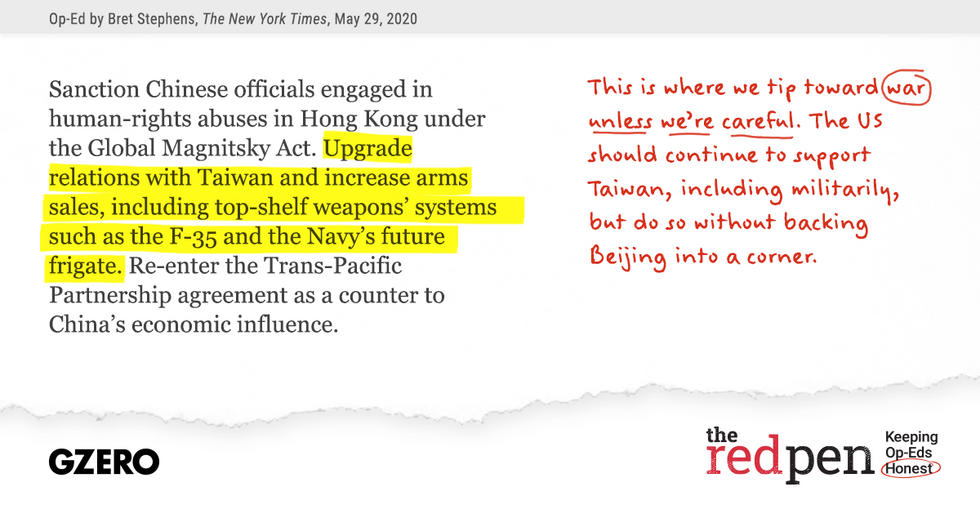

Second point: On Taiwan, Bret Stephens writes, "The United States should upgrade relations with Taiwan and increase arms sales, including top shelf weapons' systems such as the F-35 and the Navy's future frigate." And actually, I mean, if you wanted to tip into war, this is where you actually need to be the most careful. The fact is that the United States should clearly continue to support Taiwan, including militarily. But you want to do so without backing Beijing into a corner. And it's been very clear they've been red lines on both sides in this relationship. Consistently, the one for Beijing that they have maximally escalated over has been Taiwan. The Americans have every capacity to maintain status quo and there is very strong nationalism against Beijing. In Taiwan, a new nationalist elected government, stronger support for the United States, technology integration with the United States. There is no need to actively wave a red rag to the bull by trying to sell your most advanced military equipment to the Taiwanese, in addition to that.

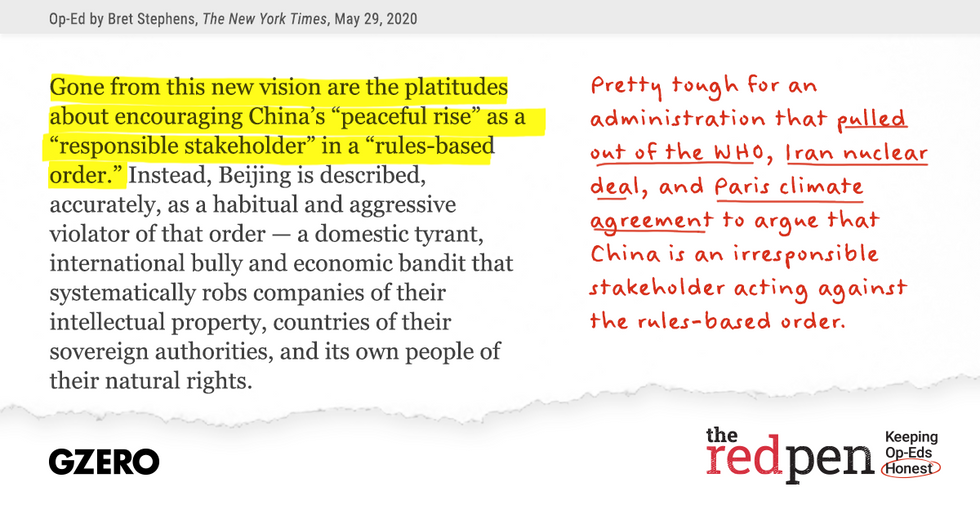

Finally, Stephens argues that the world is waking up to the fact that the Chinese are not a "responsible stakeholder" in a "rules-based order." And it is certainly true that China is not, has not been a "responsible stakeholder." But of course, keep in mind that "responsible stakeholder" for the Chinese means living by American rules in American institutions that the Chinese don't get a say over. Now, the United States is actively ripping up that script right now in terms of not being interested to follow the rules of a lot of those institutions. Whether it's the World Trade Organization or the World Health Organization. Of course, the withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. So, I mean, if the question is, do we expect the Chinese to align more with the Americans? The answer is no. Do we expect the Americans to align more with the Americans and bring the Europeans and others along? The answer is we could be doing an awful lot more by trying to lead by example.

So, in conclusion, we are not at the precipice of war. This is not the Rhineland moment. But it is indeed a very dangerous period of time between the Americans and Chinese. And ones that if we did a better job, we could have a lot more allies playing in our favor.

The US can compete with China without starting a new Cold War

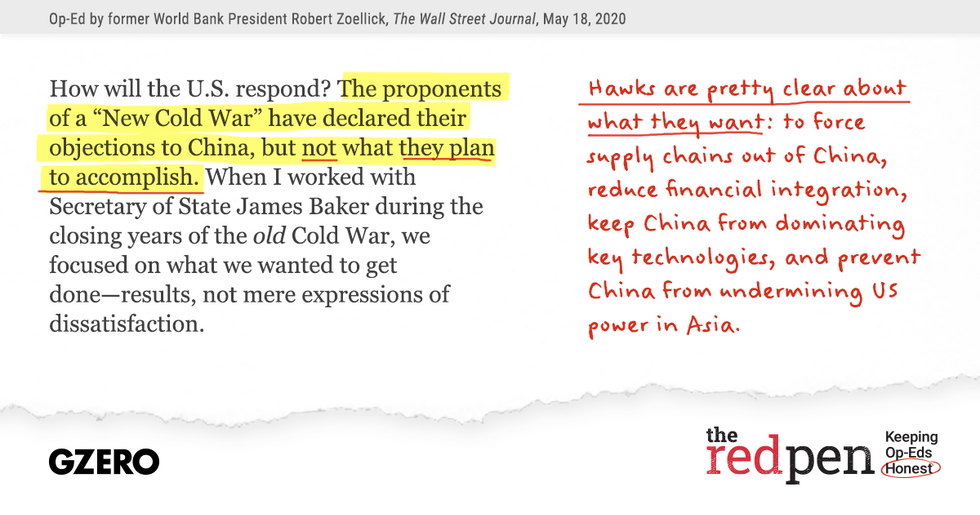

Have you ever read a major op-ed and thought to yourself, "no! no! no! That's just not right!" Us too. This week, Ian Bremmer is joined by analysts Kelsey Broderick and Jeffrey Wright to take the Red Pen to former World Bank president Robert B. Zoellick's Wall Street Journal op-ed.

Hawks are pretty clear about what they want: to force supply chains out of China, reduce financial integration, keep China from dominating key technologies, and prevent China from undermining US power in Asia.

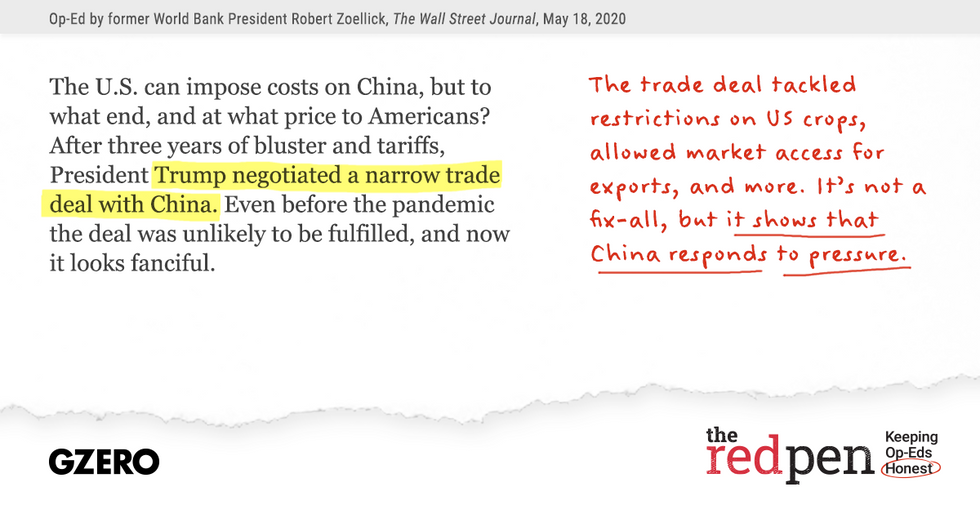

The trade deal tackled restrictions on US crops, allowed market access for exports, and more. It's not a fix-all, but it shows that China responds to pressure.

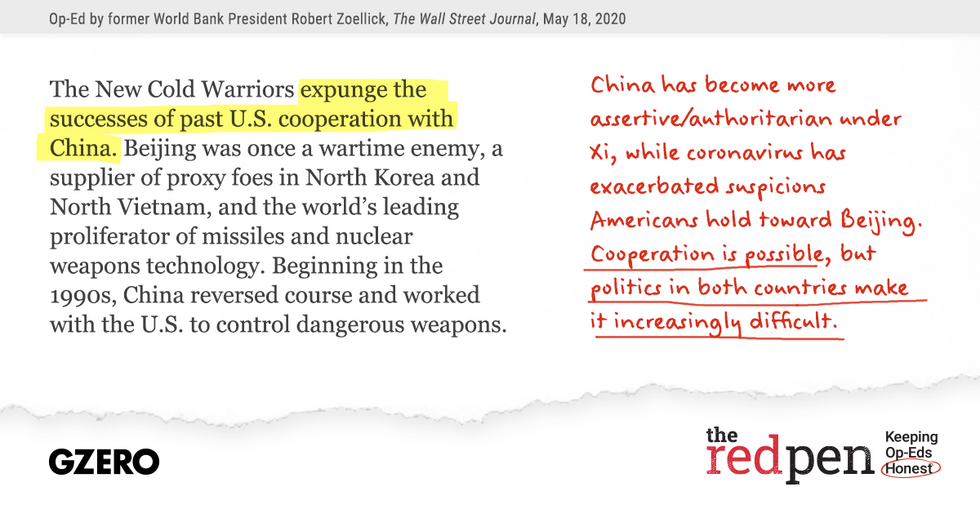

China has become more assertive/authoritarian under Xi, while the coronavirus has exacerbated suspicions Americans hold toward Beijing. Cooperation is possible, but politics in both countries make it increasingly difficult.

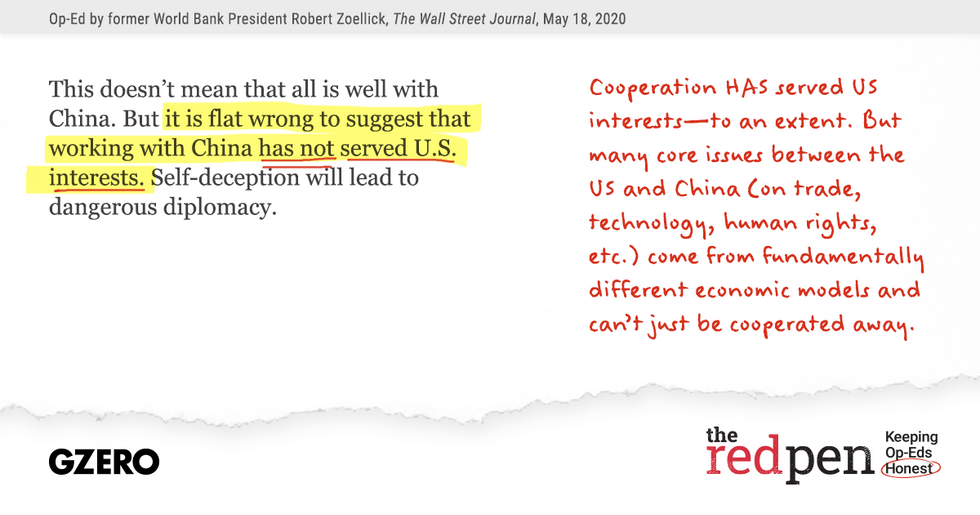

Cooperation HAS served US interests—to an extent. But many core issues between the US and China (on trade, technology, human rights, etc.) come from fundamentally different economic models and can't just be cooperated away.

—With research by Kelsey Broderick and Jeffrey Wright