Closing the Gap

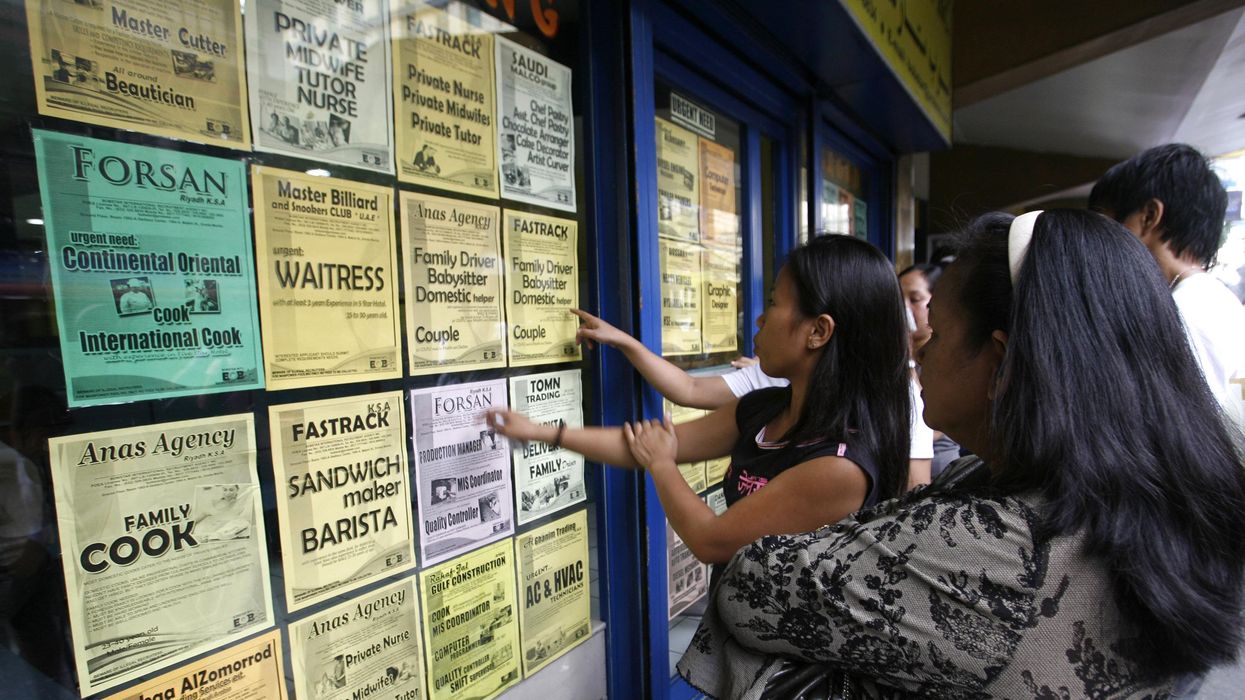

The debilitating cost of remittances

Dilip Ratha knows how hard it is to work abroad and send money home. Why? Because he had to go through the same hoops when he was a migrant. It's the inconvenience and the cost, the World Bank's head of KNOMAD and lead economist says during a livestream conversation on closing the global digital gap hosted by GZERO in partnership with Visa.

Nov 05, 2022