What We're Watching

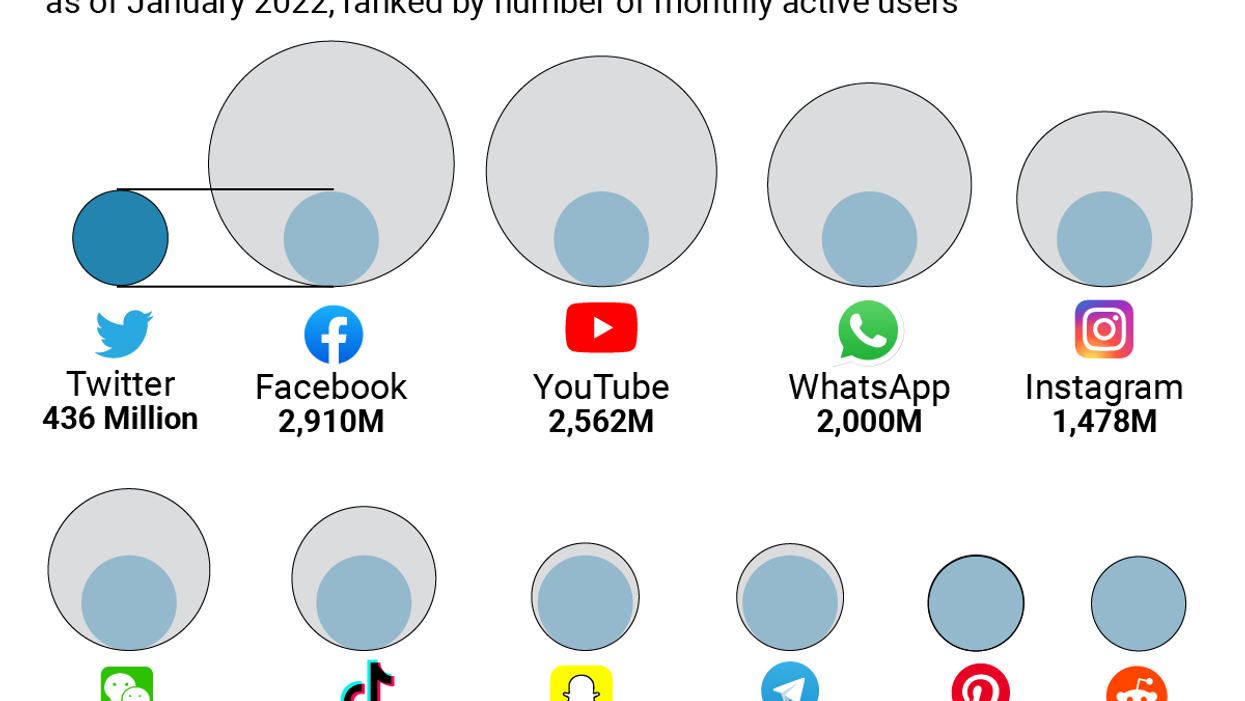

TikTok ban likely to be upheld

On Friday, the Supreme Court appeared poised to uphold the TikTok ban, largely dismissing the app’s argument that it should be able to exist in the US under the First Amendment’s free speech protections and favoring the government's concerns that it poses a national security threat.

Jan 13, 2025