by ian bremmer

Hold us accountable: Our biggest calls for 2023

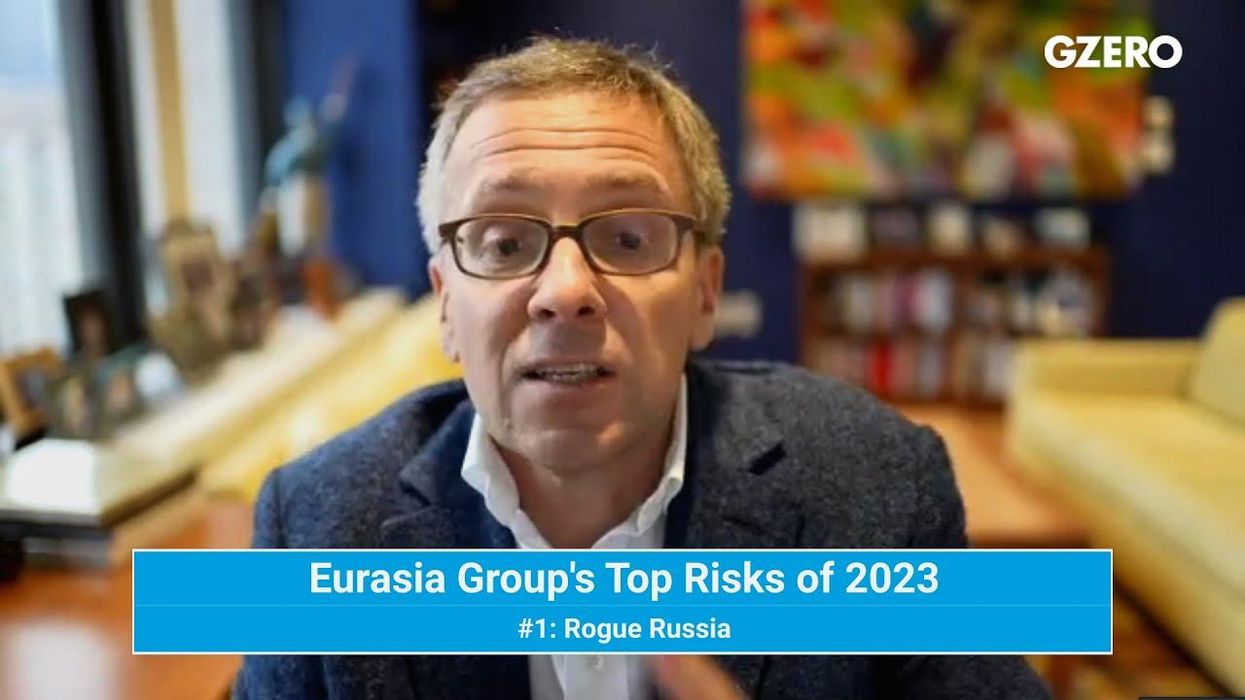

Every year, Eurasia Group releases its Top 10 geopolitical risks for the year ahead. You’ll see the 2024 edition next Monday. But an honest analyst looks back at past forecasts to see (and acknowledge) what he got right and wrong, and I’m going to do that here and now.

Jan 03, 2024