Trending Now

We have updated our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use for Eurasia Group and its affiliates, including GZERO Media, to clarify the types of data we collect, how we collect it, how we use data and with whom we share data. By using our website you consent to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy, including the transfer of your personal data to the United States from your country of residence, and our use of cookies described in our Cookie Policy.

{{ subpage.title }}

Condoleezza Rice

Pioneering Black American leaders in US foreign policy

Who exactly are the people representing America to the world? Chances are they’re “pale, male, and Yale”, as the saying goes. Even in 2024, the US Foreign Service – especially in senior positions – doesn’t look like the rest of America. African Americans, people of color, and women continue to encounter barriers to influential roles.

However, some Black diplomats — like UN Ambassador Linda Thomas Greenfield — have broken this racial ceiling and helped reimagine what an American envoy can be. Her predecessors, through the sweep of US history, encountered discrimination and racism both domestically and abroad and left an indelible mark on US foreign policy. To mark the end of Black History Month, GZERO highlights the stories of a select few:

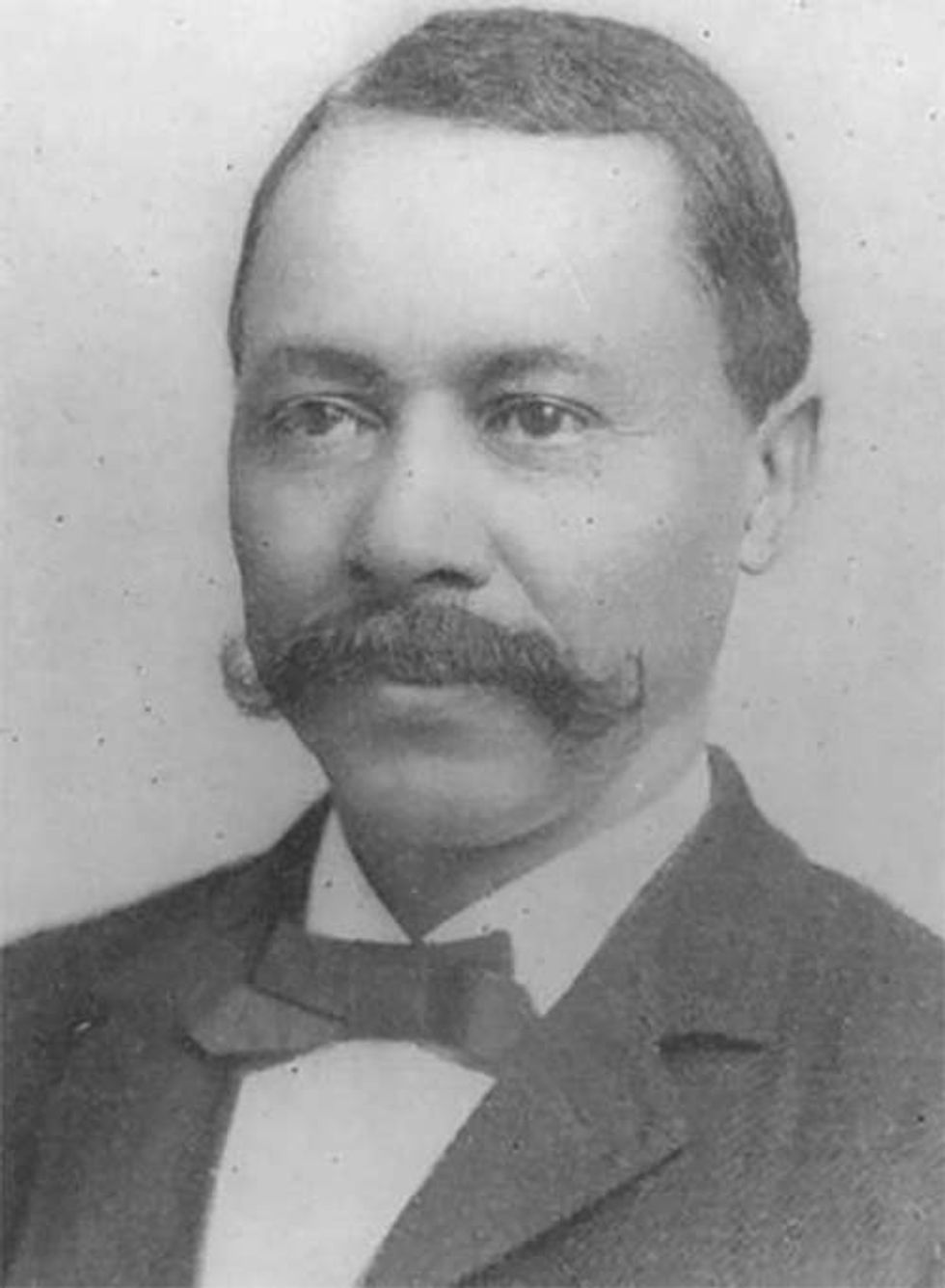

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Ebenezer Don Carlos Basset

Fair Use/National Museum of American Diplomacy

Born into a free Black family in Connecticut in 1833, Bassett broke racial barriers from the very onset of his career. He was the first Black student admitted to the Connecticut Normal School and taught at the pioneering Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia in the years before the Civil War.

His impassioned polemics for abolition and equal rights during the war thrust him into the political spotlight. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him minister to Haiti and the Dominican Republic in 1869, Basset became the first African American to serve as a diplomat anywhere in the world. Upon his return to the United States, he served as American Consul General for Haiti in New York City.

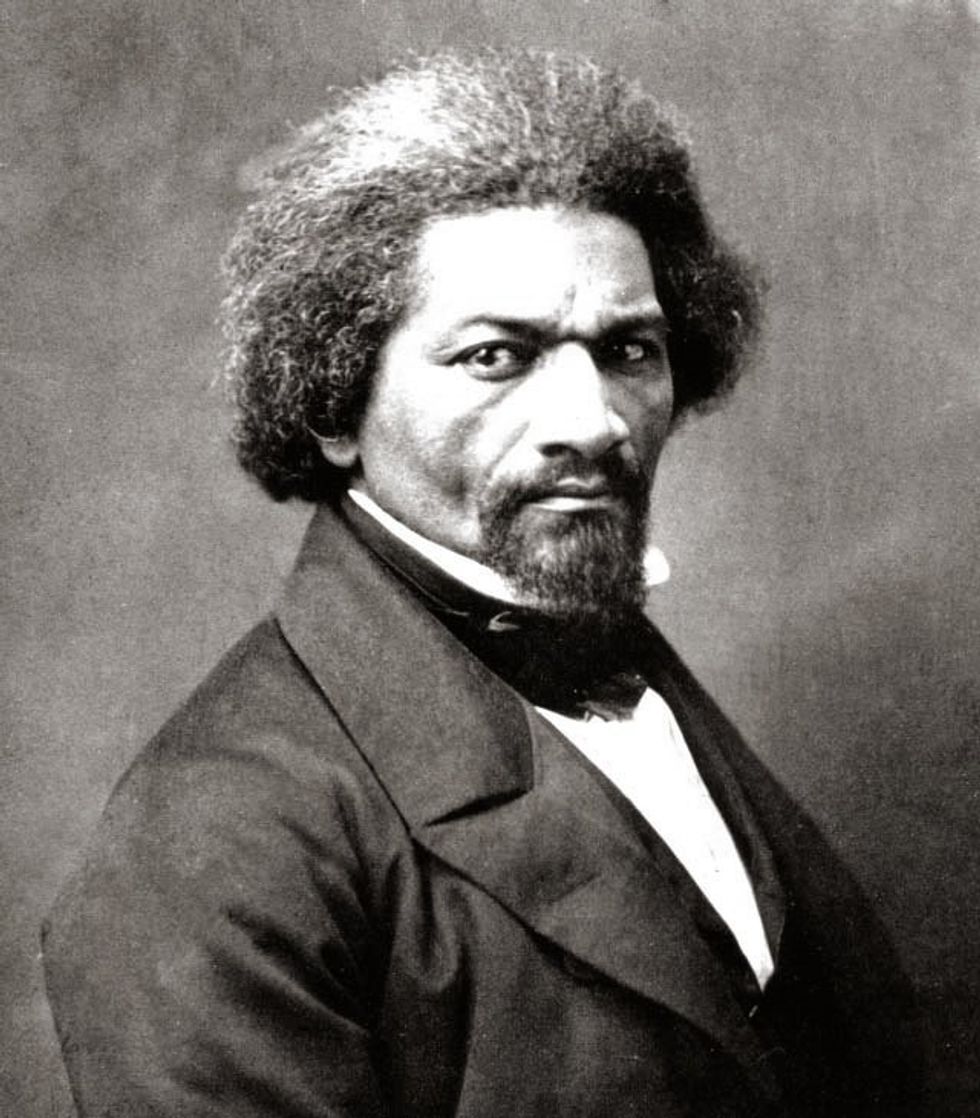

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass

Wiki Commons

Frederick Douglass, renowned abolitionist and orator, served as the United States minister resident, and consul-general to Haiti and Chargé d'affaires for Santo Domingo in 1889, appointed by President Benjamin Harrison. However, Douglass resigned in 1891, opposing President Harrison's aggressive territorial ambitions in Haiti. Haiti nonetheless honored Douglass by appointing him as a co-commissioner of its pavilion at the 1892 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His principled stance against imperialism cost him his diplomatic career and underlines the tension Black diplomats still may feel navigating the predominantly white and upper-class U.S. Foreign Service.

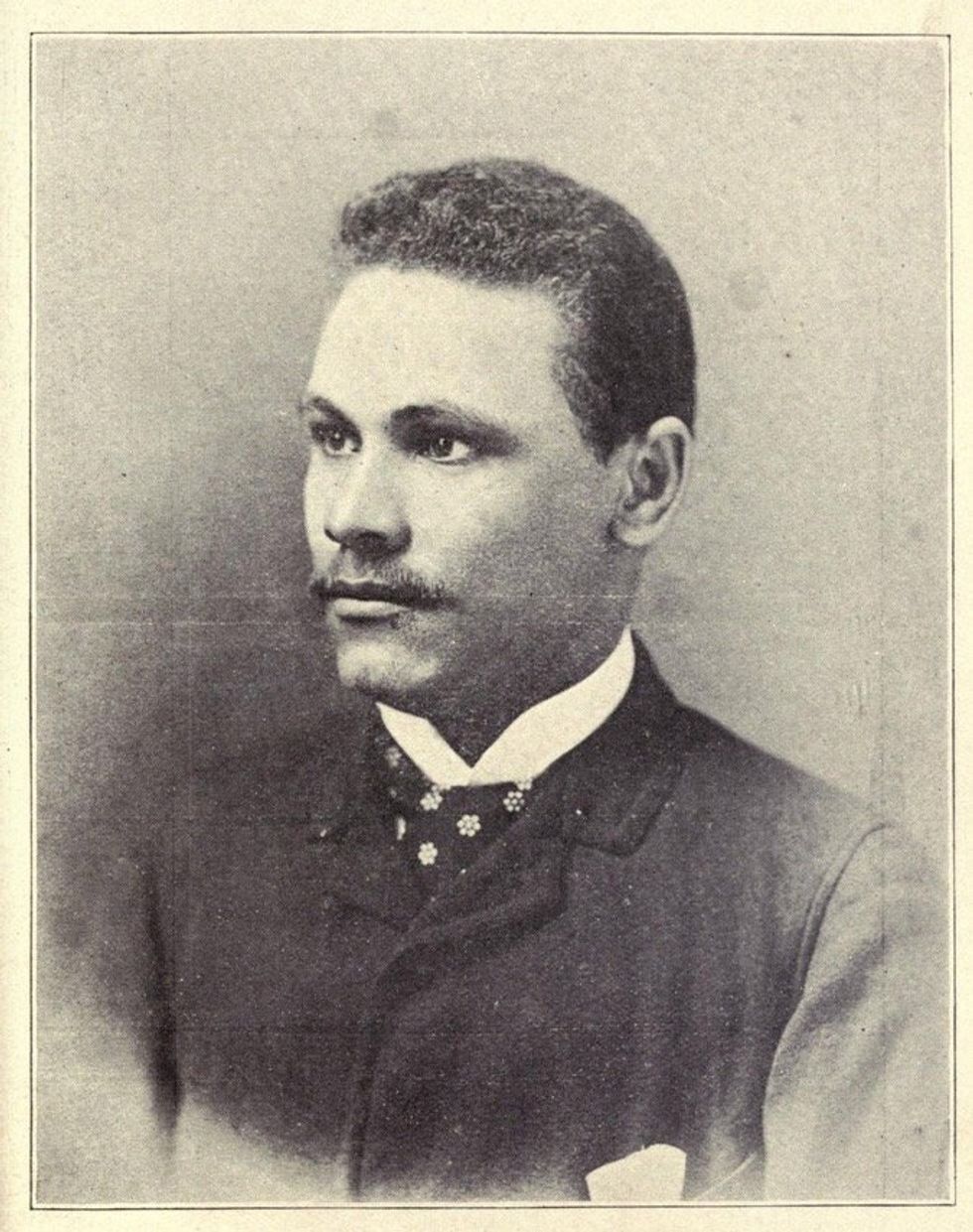

William Henry Hunt

William Henry Hunt

Wiki Commons

Hunt was born into slavery in Tennessee in 1863, the son of Sophia Hunt and the man who enslaved her. Upon emancipation, his mother took him to Nashville, where access to education allowed him to attain a post in the US Consulate in Madagascar eventually. He went on to serve in consular roles spanning from Liberia to France until his retirement on December 31, 1932, pioneering a path for Black diplomats in the 20th century.

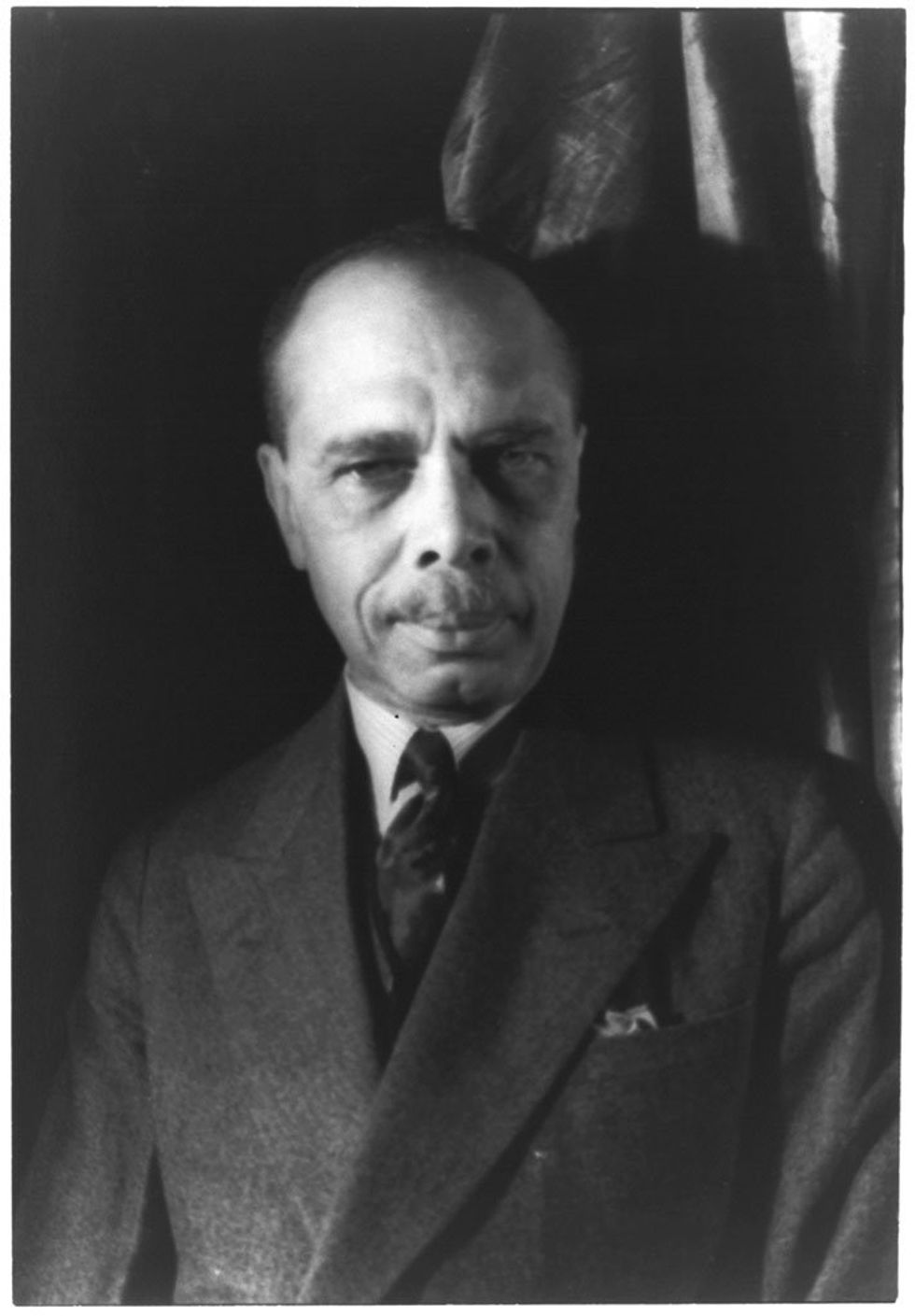

James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson

Library of Congress/Flickr Commons

Johnson served as a consul in Venezuela from 1906-1913, under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, he’s best remembered for contributions to the African-American cause that transcended diplomacy. He was a leading figure in the early days of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – effectively its executive officer from 1920 – and wrote “The Autobiography of An Ex-Colored Man.” He also co-wrote "Lift Every Voice and Sing," often referred to as the Black National Anthem, and established the "Daily American," the first Black newspaper.

Ralph Bunche

Anefo photo collection. Dr. Ralph Bunche in Stockholm with the widow of Count Folke Bernadotte. April 10, 1949. Stockholm, Sweden.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Ralph Bunche was arguably the most prominent African American diplomat of the twentieth century. He worked at the State Department from 1943 to 1971, serving under every president from Franklin Roosevelt to Richard Nixon. His initial focus on civil rights for African Americans evolved into a global human rights advocacy. He played a pivotal role in the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the adoption of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In 1950, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation efforts in the Palestine conflict, and in 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

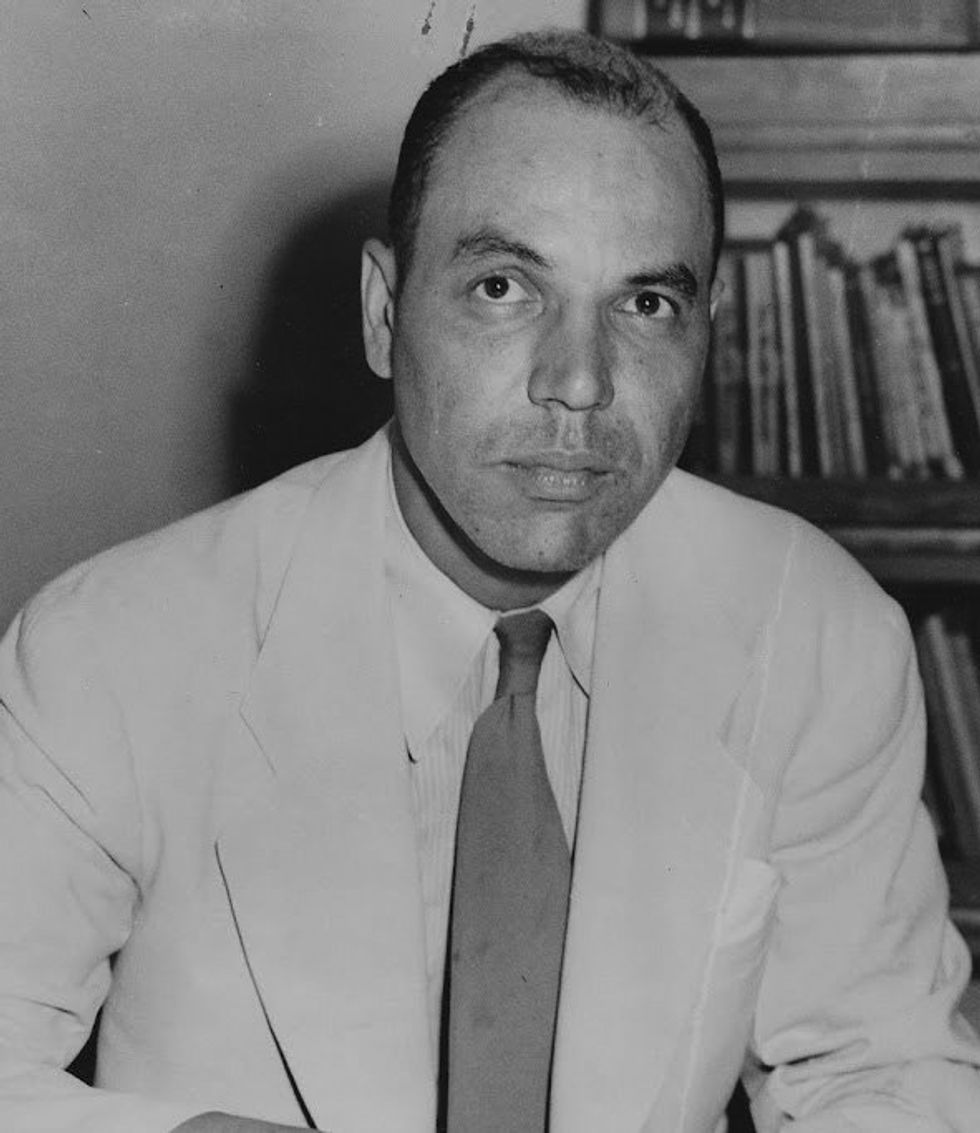

Edward Dudley

Edward Dudley

Fair Use/Flickr

Dudley was named minister to Liberia in 1948 and then an ambassador when the US raised its diplomatic mission to the embassy level the following year under the administration of Harry Truman. During this period, he and a few other Black diplomats were instrumental in the dismantling of the “Negro Circuit”, which limited the Black diplomatic corps to undesirable posts in select countries—often African and predominantly Black countries—while their white counterparts were transferred all over the world.

Clifton R Wharton Sr

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Norway Clifton R. Wharton, Sr., 3:50 PM. President John F. Kennedy sits with US Ambassador to the Kingdom of Norway, Clifton R. Wharton. Oval Office, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Wharton was the first African American to pass the rigorous Foreign Service examination and benefitted from the advocacy against the “Negro Circuit.” He worked across embassies and consulates around the world. He was the first Black career diplomat to lead a US mission in Europe as Minister to Romania, appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower. Wharton was appointed a US representative to NATO—a first for Black Americans—and a UN delegate. USPS issued a stamp as a tribute to his impeccable service 16 years after he passed.

Carl Rowan

Meeting with the US Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan, 11:53AM. President John F. Kennedy meets with newly-appointed U.S. Ambassador to Finland, Carl T. Rowan right. West Wing Colonnade, White House, Washington, D.C.

IMAGO/piemags via Reuters Connect

Rowan rose to fame as a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune, writing an acclaimed series about racism in America. He sat and interviewed the most prominent figures in America, including then-Senator John F. Kennedy, on the campaign trail in 1960. Impressed, Kennedy appointed Rowan Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, where he played a crucial role at the United Nations during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Later, he was the first Black director of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and, at that time, was the highest-ranking African American in the US government.

Patricia Roberts Harris

Patricia Roberts Harris

Fair Use/United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

The first African American woman to serve as a US ambassador, Harris served in Luxembourg between 1965-67 under the administration of President Lyndon Johnson. After her tenure, she was nominated as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet in 1977. Her confirmation meant she became the first Black woman to direct a federal department.

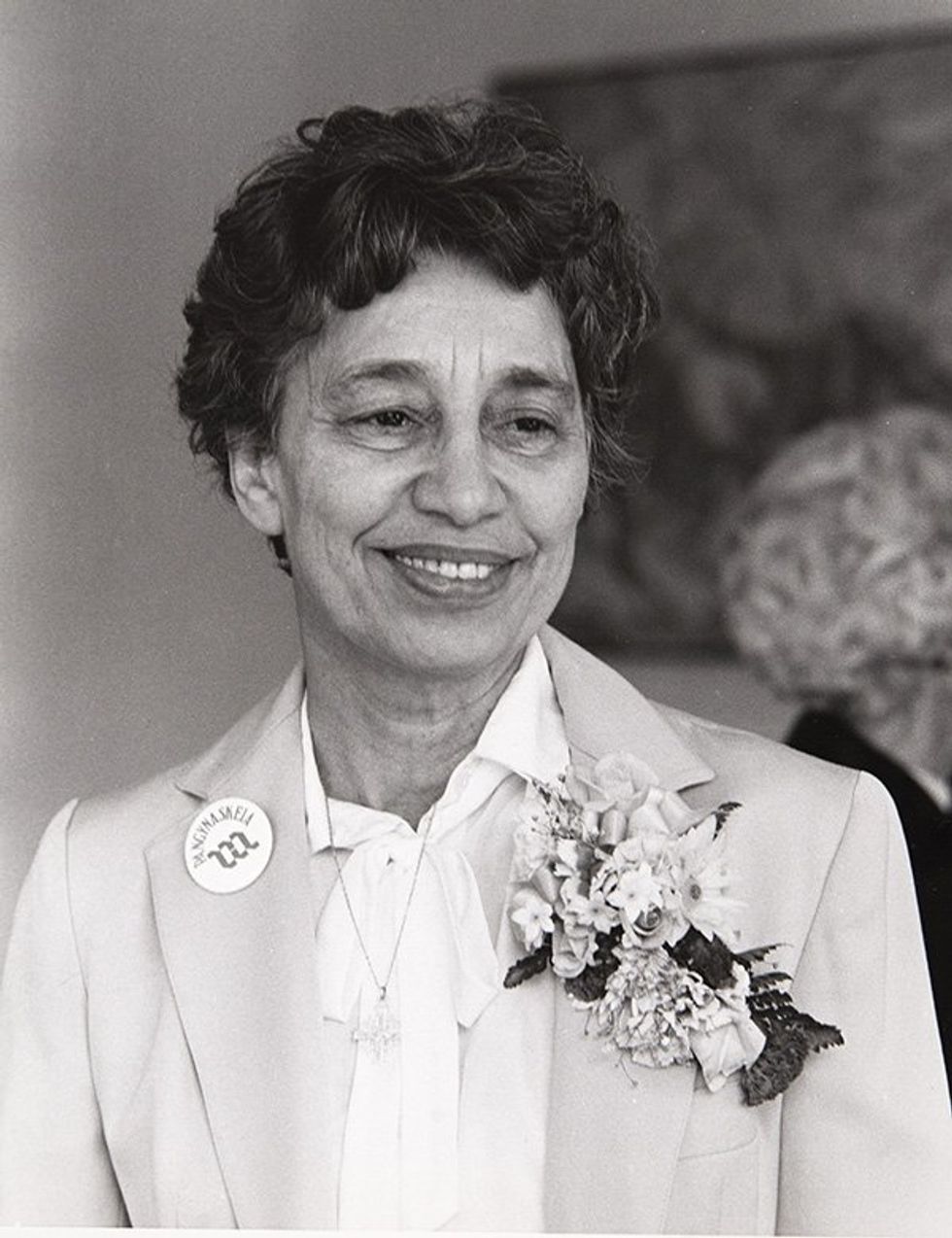

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Mabel M. Smythe-Haith

Fair Use/Flickr

Smythe-Haithe was the first Black woman to hold an ambassador position in Africa and the second Black female ambassador during the Carter Administration. Prior to her diplomatic career, she worked with the NAACP on the landmark Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case alongside Thurgood Marshall. She also served on the State Department’s Advisory Council for African Affairs under President John F. Kennedy.

Colin Powell

U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell makes a point as he testifies May 15, 2001, before the Senate approprations subcommittee for programs of the State Department for the fiscal year 2002.

Reuters

Born in New York to immigrant parents from Jamaica, Powell became the first Black Secretary of State under President George Bush in 2001 after a 35-year career in the military. Powell oversaw foreign policy during the worst national disaster of recent memory, the September 11 attacks. Despite accolades, his tenure was marked by controversy, notably his defense of the 2003 Iraq invasion before the United Nations Security Council. He resigned upon President Bush's 2004 reelection, but his tenure coincided with a surge in black diplomats in the Foreign Service.

Condoleezza Rice

U.S. Secretary of State-designate Condoleezza Rice sits before her U.S. Senate confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, January 18, 2005. Rice vowed to press diplomacy in President Bush's second term after he was criticized for hawkish and unilateral policies in his first four years.

Larry Downing/Reuters

Appointed as National Security Advisor by President George W. Bush in 2002, Rice made history as the second Black person and first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State in 2005. In that role, she advocated for Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza and ceasefire negotiations with Hezbollah in 2005 – though the Bush administration’s legacy in Iraq and Afghanistan dominates memories of her tenure. Under her leadership, the State Department witnessed an increase in Black diplomats, although this progress saw setbacks under President Donald Trump.

- The 1619 Project’s creator Nikole Hannah-Jones discusses its cultural impact ›

- The history of Black women judges in America ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black immigrants in the US ›

- The Graphic Truth: Black representation in the US Congress ›

- Why do Black people feel "erased" from American history? ›

- Ron DeSantis and the latest battle over Black history ›

- Will foreign policy decide the 2024 US election? - GZERO Media ›

- Kamala Harris makes her case - GZERO Media ›

US-China: Commerce Secretary Raimondo visit a success

Ian Bremmer shares his insights on global politics this week on World In :60.

US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo just visited China. Was it a success?

Yeah, the bar is low, the expectations are low. But the meeting was successful. In particular, we have the announcement of two more lanes of engagement within the US Department of State and Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. One on commercial disputes, one on export controls. And, you know, given that these are sides that were barely talking to each other a year ago, that is an incremental positive. Also on the back of the Chinese economy continuing to underperform and the Chinese response being very incremental, they're not looking for any economic blow up with the US. And Raimondo, like Janet Yellen, who's been there recently, like John Kerry's been there recently, are the warmer, more pro-integration faces of the Biden administration. Haven't heard so much from Kurt Campbell recently. So all of that is nominally positive.

How will the Ukraine counteroffensive unfold?

Well, so far it is also marginal improvement for Ukraine. A little bit more land being taken in the southeast. One of three Russian lines of defense being broken in one place. You know, the Russians are holding pretty well defensively. The more significant counteroffensive is Ukrainian drone capabilities striking more targets inside Russia, in Moscow, in Pskov, in lots of places. And, you know, that's not about Ukraine getting their territory back. That's about Ukraine showing that their military can exact damage to the Russians. You know, on the one hand, that's a positive for Ukraine's capabilities. It's, of course, concerning in terms of the level of escalation that we might end up seeing between Ukraine and Russia and potentially between Russia and NATO. But so far, still relatively limited real news about how the counteroffensive is going.

Finally, what's next for the US economy?

Well, I'm not an economist, so I'm not going to answer that directly. What I will say is the fact that a lot of Americans continue to suffer from high levels of inflation means that even though the performance of the US economy, compared to the rest of the advanced industrial economies is actually quite strong coming out of the pandemic. That's true in terms of low unemployment levels. It's true in terms of comparatively low inflation. It's true in terms of comparative GDP growth. But overall, a lot of working class and middle class Americans still do not feel that the economy is doing well for them. Some of that is political perception, tribalism. Some of that is really suffering and a lot of inequality in the United States that hasn't been structurally addressed and probably won't be. There's more downside here for Biden in the next 12 months than there is upside from getting a Goldilocks economy going. And so on balance, I'd say this is an area of concern. But again, right now, hard to say that this is much more than incremental improvements.

Henry Kissinger turns 100

Ian Bremmer's Quick Take: Hi everybody. Ian Bremmer here. Happy Tuesday to you after Memorial Day weekend, and I thought I'd talk for a bit about Dr. Kissinger since he's just turned 100 old. I'm pretty sure he's the only centenarian that I know well. And lots of people have spoken their piece about how much they think he's an amazing diplomat, unique, and how much they think he's a war criminal, unique. And maybe not surprising to anyone, I'm a little bit in between those views.

I have known him for a long time. I remember first time I met him was around 1994. I'd just come back from Ukraine and I introduced myself to him at some event in New York. And he was interested in what I had to say. And so why don't you come and have lunch with me? Which was kind of surprising since he didn't know me at all. And I thought, well, maybe he's just getting rid of me to talk to other people that are in line. But a couple days later, I find myself in his office having tea sandwiches and talking about Ukraine and the context of Russia relations, Europe relations and US. It could have been with a professor of mine or some colleague, the kind of discussion we were having. It didn't feel like he was being pompous or talking down to me. Spoke like he wanted to understand what I had learned from my relationships on the ground and my analysis and challenge it against his own. So that was pretty interesting.

Of course, I will tell you at that point, the reading that I had done of Kissinger was mostly in his own words on diplomacy and from some professors of mine at Stanford and the colleagues there that generally were very well-disposed to him. Since then, I probably sit down with him a few times a year and talk about global issues. And it's always interesting to hear his perspective. I would say that when it comes to broad international relations, he is of a very specific view and school, very transactional, very strategic. He's also of a certain time and place in the sense that he still doesn't believe that Europe really matters, doesn't accept that the European Union has become much stronger, much more capable as an institution than it was 10, 20, 30 years ago, than it was when he was saying, "Who do I call in Europe? Give me a phone number. They don't have one."

On the other hand, he's retooled himself considerably to truly learn about and understand artificial intelligence, and not just from a layman's perspective, but understand the policy implications. And to do that at the age of 100 is pretty extraordinary. I consider AI to be an utter game changer, geopolitically more important than any transformation I've seen on the global stage since I did my PhD some 30 plus years ago.

But for Kissinger to do that at 100 is quite something. And the fact that he has the wherewithal and the acumen to do that, I'm sure says a lot about why he still is put together as he is. There was an event that I did for the Young President's Organization, a few thousand folks, a few months ago. And this was on a big stage and Kissinger was going to give a masterclass, but they needed someone to engage with him for an hour, and he asked if I'd do it. So I said, "Sure." And what was interesting about it was, I mean, I sat in close to him so that he could hear everything I was saying clearly. But I mean, for an hour, this was a very serious conversation, frankly, as good as anyone else I've spoken with on my show over the course of the last several years, and again, doing that at 100. So put all of that together, you have to be impressed in the sense that it makes an impression upon you. Whether negative or positive, it's an impression that someone can do that at his age.

So that that's all of my relationship with him. And when I disagree with him, I say so, and do it more strongly privately than I do it publicly, in part because his willingness to respond to that usefully, publicly is fairly limited. And so you don't get value out of it. But that doesn't mean that I'm a big proponent of his worldview. And some of that is true today. A lot more of that is true, of course, historically. You learn a lot about someone by what they do when they're in a position to really do something, when they're in a position of power, when it matters. For example, I'd like to believe that when the chips were down and I had the ability to either keep my mouth shut or say something publicly about Elon Musk, and it would've been a lot more convenient to do the shutting your mouth, that I used my platform hopefully to make a more positive difference.

And I think that that's in a very small way. In a very big way of course, when you're National Security Advisor, Secretary of State, you have real power in your hands and you make decisions that destroy people. That says a lot about who you are. And I obviously can't in any way justify or support or align myself with a lot of the decisions that Kissinger has taken. And you look at Chile and the support for Pinochet and the coup overthrowing a democratically elected government, something that he strongly and individually supported despite lots of opposition inside the Nixon administration and from President Nixon at the time. I think about Kissinger's support for Suharto in Indonesia and the killing in East Timor. Over a hundred thousand innocent civilians dead from what now has an independent country, but at the time, was the Americans happy to privately support essentially a genocide. And that was a Kissinger policy. This was American exceptionalism. It was the opposite of that. And Vietnam, a lot of people take responsibility for the murderous interventions in Vietnam and not something that the Americans learned enough from. But specifically around Cambodia and a bombing campaign that was conducted in secret, which was denied for a long time by Kissinger. And again, over a hundred thousand civilians dead. And then one of the most murderous regimes we've ever seen in the 20th century comes in the Khmer Rouge because the country had been so destabilized by the Americans and by Kissinger's decision that led to the deaths of millions more.

So that's on his hands individually. And I guess you live to be 100 and you have that kind of power, few people are going to be proud of everything they did, but this is a very different kind of decision. I will say that part of meeting Kissinger turned me off from power. The fact that someone who had been a Harvard professor who I respected so much from the writings that I read of his, and then as you learn what that person, despite what they're like when they meet you, had done when they were in power, just turns you off from power. It makes you feel like that's something you don't want to be any part of. That was my initial sort of knee-jerk reaction. I think it's become more nuanced since then.

But you can't have a retrospective about one of the men that has had the greatest impact on American diplomacy and its influence around the world without recognizing just how negative some of that has been. And I will say that in today's very polarized environment, Kissinger is one of the people probably most responsible for the fact that when people around the world see that you're an American and do international affairs, they assume that your views of the world are equally high-handed, hypocritical, disdainful of the rights of human beings as humans. I mean, in some fundamental way, I'm probably the antithesis of realpolitik because I actually believe first and foremost that if there are 8 billion people on the planet, they all kind of count the same. And the fact that that means more to me than any individual citizenship is pretty much not any of what Kissinger did when he was Secretary of State, which is kind of sad for someone that's that bright and someone that has the capacity to do so much more.

So that's my view of Kissinger at 100. Probably a little different than a lot of what you've heard thus far on the topic, but for Memorial Day in particular, maybe a more appropriate read. So that's it for me. I hope everyone's well and take it easy this week.- Who is Tony Blinken? ›

- Colin Powell, trailblazing soldier and statesman, dead at 84 ›

- 75 years later: What can the Marshall Plan teach us about rebuilding Ukraine? ›

- Fault lines are emerging in the Western front against Russia ›

- In Bangladesh, a powerful premiership is transforming into a brutal dictatorship ›

US-Canada can and will extract critical minerals sustainably, says top US diplomat

Ever heard of critical minerals? Well, there's a reason they are called that way — and it has a lot to do with clean energy.

At the US-Canada summit in Toronto, GZERO's Tony Maciulis asks Jose Fernandez, US Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy and the Environment, about why these minerals are such a big deal and what the US and Canada are doing to secure supply.

Fernandez also shares his views on how critical minerals can be mined sustainably, and more broadly on how the two countries can work together to tackle this and other issues relevant to the fight against climate change.

For more, sign up for GZERO North, the new weekly newsletter that gives you an insider’s guide to the world’s most important and under-covered trading relationship, US and Canada.

- Biden-Trudeau talks focus on immigration and defense ›

- 3 ways mining companies can help protect biodiversity ›

- Subsidy game could hurt Canada-US relations ›

- US green subsidies pushback to dominate Biden's Canada trip ›

- Frenemies? Get insights on the US-Canada relationship from GZERO North ›

- Canada has lower risk appetite than the US, says think tank chief - GZERO Media ›

- What the US and Canada really want from each other - GZERO Media ›

- Podcast: How healthy is the US-Canada relationship? - GZERO Media ›

Colin Powell's legacy

Jon Lieber, head of Eurasia Group's coverage of political and policy developments in Washington, shares insights on US politics:

What is the legacy of Colin Powell?

Former Secretary of State Colin Powell tragically died of complications of COVID-19. He was the first Black Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the first Black National Security Advisor and the first Black Secretary of State. And he leaves a legacy of a long career, dedicated almost entirely to public service.

Powell's legacy will probably be defined by two things. One is the creation of the Powell Doctrine developed in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, which gave a blueprint for US military action that had to be overwhelmingly decisive and with a clear exit plan to avoid the kind of quagmire that the Vietnam War became. The second legacy item is his unfortunate role in making the case for the Iraq War, with a presentation in 2003 in front of the UN on Iraq's possession of chemical weapons, that later turned out to be false. This was a key justification used at the time by the Bush administration and a stain on Powell's otherwise excellent reputation.

Unfortunately, because Powell died of complications of COVID-19, he had been treated for multiple myeloma, which weakens the immune system and he was fully vaccinated. This means his death will become a political football among the 10% to 15% of Americans who are hardcore anti-vaxxers, and who claim the vaccines don't actually protect you from COVID-19. A sad day for the Powell family and a tragic day for America.

Returning Cuba to terror list is an 11th hour move by Pompeo and Trump

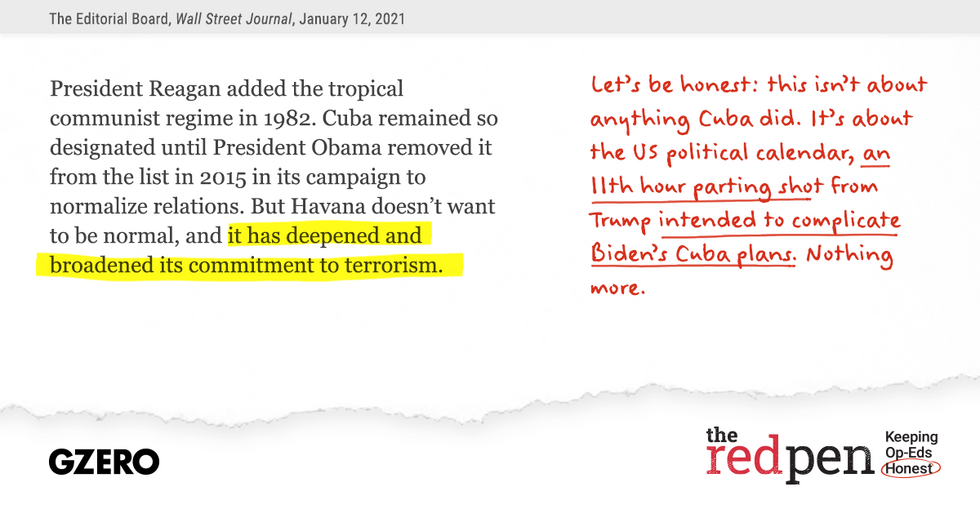

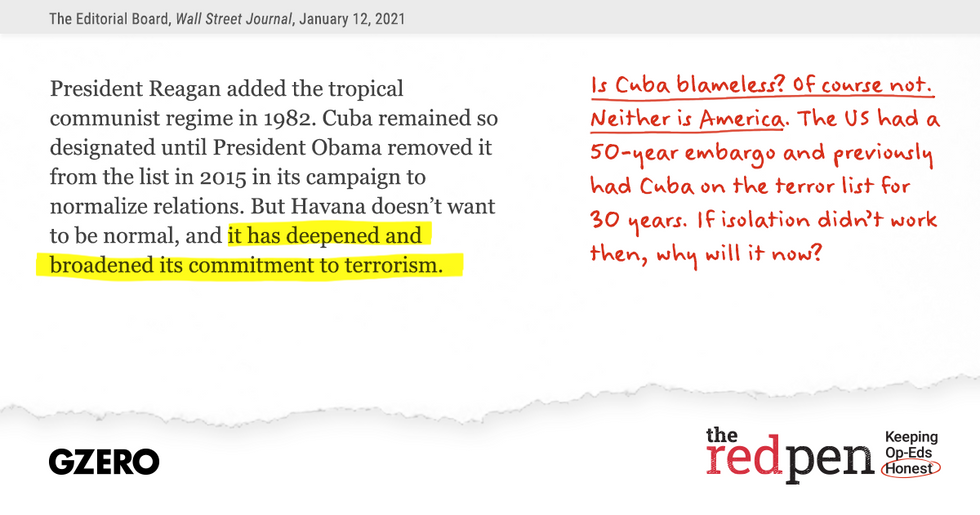

Does Cuba belong back on the US's State Sponsors of Terrorism list? The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board showed their support for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's decision on this issue in a recent opinion piece, "Cuba's Support for Terror." But in this edition of The Red Pen, Ian Bremmer and Eurasia Group analysts Risa Grais-Targow, Jeffrey Wright and Regina Argenzio argue that the WSJ's op-ed goes too far.

We are now just a few days away from the official end of Donald Trump's presidency, but the impacts of his latest moves in office will obviously last far beyond Joe Biden's inauguration. There's the deep structural political polarization, the ongoing investigations into the violence we saw at the Capitol, lord knows what happens over the next few days, there's also last-minute policy decisions here and abroad. And that's where we're taking our Red Pen this week, specifically US relations with Cuba.

The Trump administration this past week declared Cuba a "state sponsor of terrorism." Just to remind you, the Obama administration removed Cuba from that list in 2015 as part of a broader opening with the communist country. The Wall Street Journal editorial board is a big fan of the decision to put it back on the list.

Cuba has problems when it comes to human rights and suppression of political opponents, plus close ties to countries that the United States hardly friendly with, like Iran and Venezuela. But we think this op-ed actually goes too far, as does Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's parting shot of putting that nation back on this list.

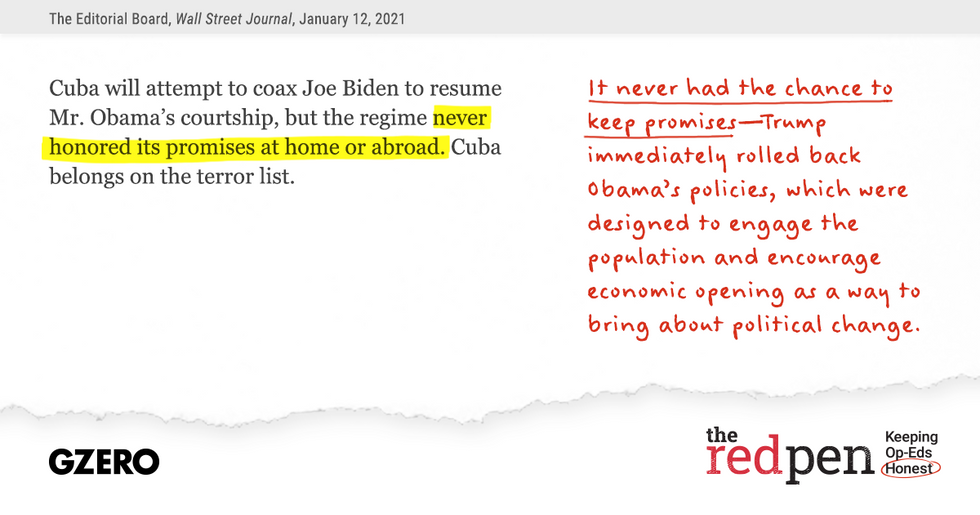

So, let's get to it. First, The Editorial Board writes that "Cuba will attempt to coax Joe Biden to resume Mr. Obama's courtship, but the regime never honored its promises at home or abroad."

Well, Cuba wasn't really given a chance, and that wasn't the point. Trump started to roll back Obama's policies immediately after becoming president. Obama intended to engage the Cuban population and encourage economic opening with the United States as a way to bring about political change. The policy was never about the communist regime's "promises."

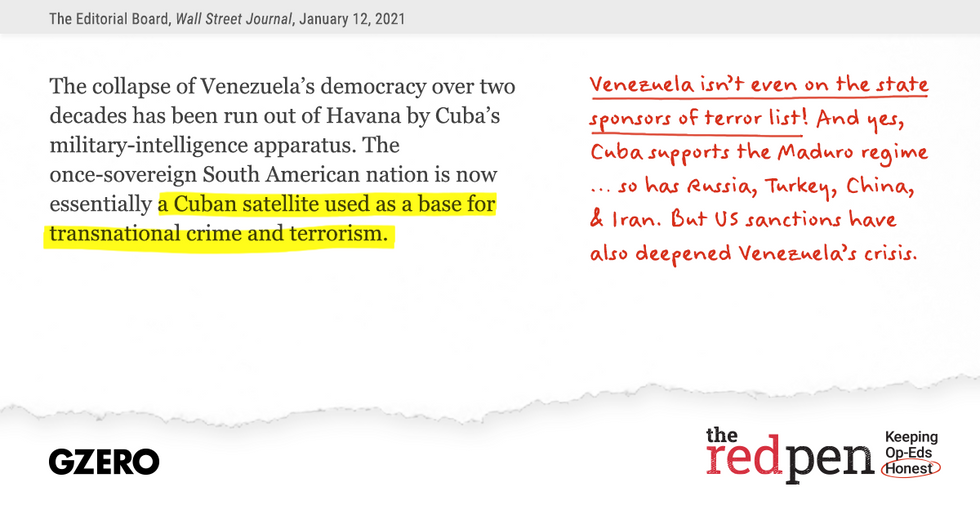

Next, the Wall Street Journal argues that Cuba is responsible for the "collapse of Venezuela's democracy." Maduro "survives in power thanks to Cuba," and Venezuela has become a "base for transnational crime and terrorism."

Now, it's true, Cuba has and does support the Maduro regime. So have Russia, Turkey, China, and Iran. US sanctions have also deepened Venezuela's crisis. And the United States doesn't seem so concerned about Venezuela being a terrorist base since Venezuela is not actually on the terrorist list itself.

The op-ed also states that Cuba has "deepened and broadened its commitment to terrorism," and that the nation harbors terrorists and criminals wanted by the FBI and other law enforcement agencies.

By this standard it's true, but many US allies would also need to make the list. Saudi Arabia for example, has long harbored people suspected of involvement in terrorist attacks. France refuses to extradite its own citizens to face US courts. And by the way, the United States has harbored many anti-Castro exiles who have committed acts of violence in Cuba.

Now Cuba is far from being blameless, but that's not the point. Why put Cuba back on this list now? The decision has a lot more to do with the US political calendar than anything Cuba has done. The 11th hour move is intended to complicate Biden's Cuba plans, nothing more.

It was Ronald Reagan who first added Cuba to the terrorism list back in 1982, and the US had embargoes in place with Cuba for nearly 50 years. Communist government is still in power and still repressive.

What makes Trump, or the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board, think this time around is going to be any different? It feels more like another mess to toss at the incoming president and his administration.

Add it to the growing pile.

US now rejects Beijing’s South China Sea claims. So what?

For decades, Beijing has laid claim to vast swaths of the South China Sea, over the objections of its neighbors and even international courts. And until two days ago, the United States had avoided taking a strong stance on the question. Not anymore.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Monday said that the US now supports a 2016 international ruling that explicitly rejects China's sovereignty claims over the sea.

Does this move matter? It's certainly an escalation for the US to reject Beijing's long-standing argument that the South China Sea is an integral part of China. From Beijing's perspective, this is meddling in China's internal affairs, notwithstanding the fact that five other countries — Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam — also claim parts of the South China Sea as their own.

But Pompeo's statement doesn't change much. For one thing, the 2016 ruling is based on a treaty — the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea — that the US itself has not even ratified.

Also, the US is late to the party. Irrespective of what Washington now thinks, China has long been quietly creating facts on the sea, as it were.

Over the past four years, China has continued building new artificial islands, complete with anti-ship missiles and military airstrips, in defiance of the US Navy's freedom of navigation operations (in which it sends its own warships through these waters as a show of force).

At the same time, Chinese fishing vessels still operate in disputed areas, over the protests of Filipino and Vietnamese captains who feel chased out of their traditional fishing grounds.

Perhaps most impressively, in 2018 China signed a memorandum of understanding to jointly explore for oil and gas in disputed areas with the Philippines, precisely the country that had brought the international suit against China in the first place.

The fact that China was able to strike such a deal with a country that had sued Beijing for encroaching on its 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea is a sign that when faced with China's economic and military might, weak claimant countries often have no choice but to bite the bullet by agreeing to share what is (legally) entirely theirs. It's also a far cry from 2012, when a standoff over a fishing shoal brought China and the Philippines to the brink of war.

Why does the South China Sea matter at all? The waters have huge strategic importance. About one-third of global shipping passes through the South China Sea, which accounts for at least 12 percent of the world's fisheries. It is also believed to hold vast untapped reserves of oil and gas.

Whoever controls the South China Sea controls the main commercial and navigation gateway to East Asia — and that's why China will never let it go.

So, what happens next? For the moment, barring some kind of miscalculation among warships — which last week overlapped naval drills in the disputed area for the first time, without incidents — full-blown conflict between the US and China over the South China Sea is hard to imagine. The costs would just be extremely high for both sides.

But absent strong pushback, China will continue to slowly and steadily expand its de-facto control over these waters in ways that can permanently alter the balance of power in the region. Tough talk from Pompeo won't be enough to stop it.