GZERO World with Ian Bremmer

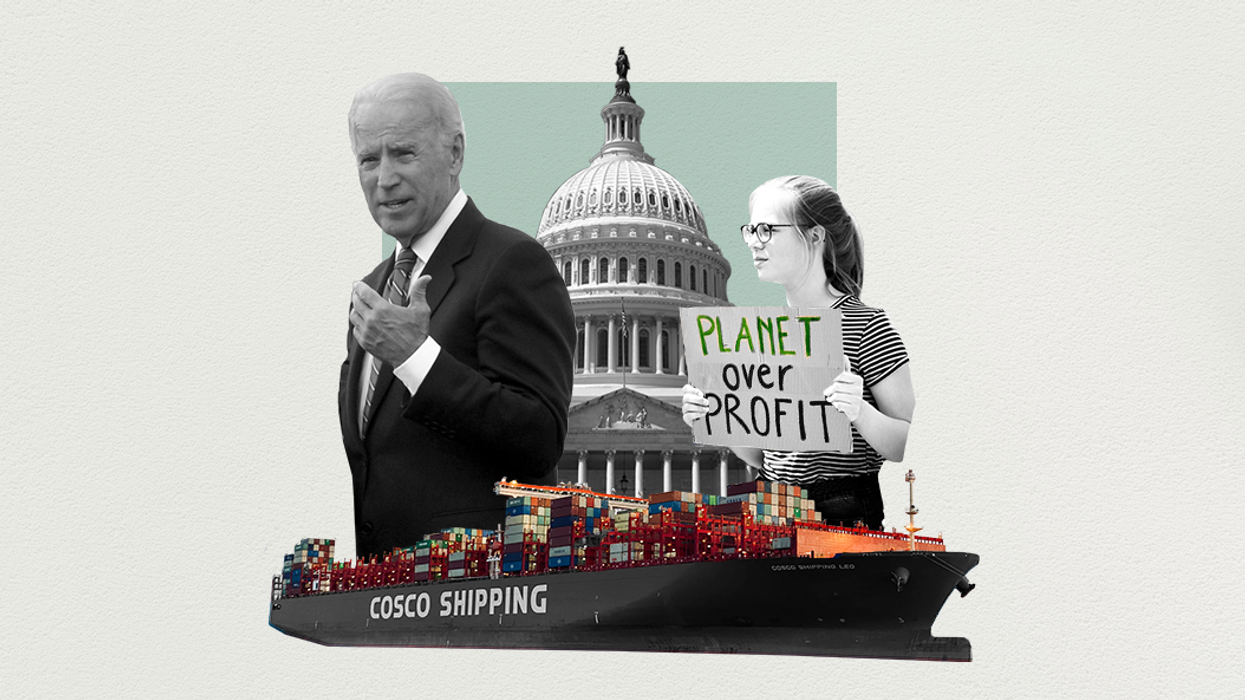

Trump’s trade war: Who really wins?

Beneath America’s shifting economic and foreign policy lies a fundamental question: What happens when its closest allies can no longer trust it? The Economist's Zanny Minton Beddoes joins Ian Bremmer on GZERO World to discuss.

Mar 24, 2025